I wrote this essay for the July issue of the SPUR (San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association) newsletter. They published it in a somewhat edited, toned-down version, of course. I have huge respect for my friend Gabriel Metcalf, who is SPUR’s executive director now (!), but of course the organization itself has a somewhat problematic past as the voice of pro-development, usually downtown-leaning interests. Be that as it may, I’ve had the pleasure of speaking at their lunch time forums a few times over the past couple of years, and participated in a panel discussion yesterday on the same theme as this issue of their newsletter: The 1905 Burnham Plan for San Francisco.

Here’s my essay…

History is cluttered with paths not taken. One of San Francisco’s most amazing unfulfilled dreams can be glimpsed in the 1905 Burnham Plan, a vision of an imperial city bedecked with monuments, buildings, and plazas worthy of ancient Rome or Greece. Allusions to grandeur notwithstanding, the Burnham Plan has influenced San Franciscans well beyond its original publication, not just for its vision of marble atheneums and flattened hilltops, but for its 19th century vision of a city harmoniously integrated with its underlying natural terrain.

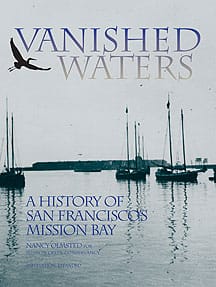

San Francisco’s history is also rich with failed plans, wild visions, and absurd development schemes that have been thwarted by concerted citizen opposition. From halting the quarrying of Telegraph Hill contemporaneous to Burnham’s Plan, to derailing the insane Reber Plan to damn the north and south Bays to create fresh water lakes (and later to stop altogether the unregulated filling of the Bay), to the mid-20th century rejection of the infamous Freeway Plan(s), San Francisco has struggled with a political process that in fits and starts has produced the city we have now. We can be proud of our predecessors’ initiatives that preserved open spaces, held back the wrecking balls to save neighborhoods and historic buildings, and created a sophisticated culture of urban appreciation.

The Burnham Plan was sponsored by the private Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco, one of whose chief leaders was former Mayor (and vitriolic racist) James Phelan. The role Phelan played in post-quake San Francisco has recently come to light, gaining control of relief funds and using his own and other private monies to fund the investigation and prosecution of the sitting Mayor and Board of Supervisors. (see Philip Fradkin’s The Great Earthquake and Firestorms of 1906). The infamous graft trials distracted and divided San Francisco during a period of historic upheaval. Intense class conflict pitted gunslingers and strikebreakers against streetcar men, laundry workers, iron workers and more. A lot of that era’s corruption was focused on gaining control of San Francisco’s basic infrastructure, from the new electricity and gas to water and rail transit. Decisions made during this hotly contested period still shape our urban life today (PG&E was founded in 1905; plans made by Phelan in this period led to the 1913 Raker Act which gives us Hetch Hetchy water, but not the public power we are mandated by law to have).

In spite of the preponderant vested interests that commissioned the Burnham Plan, it was never implemented. A plan of this scale would require someone or some group capable of overriding the entrenched interests of property owners, but able too to present that power grab as in the larger public interest. The first decade of the 20th century did not produce a local version of New York’s Robert Moses, San Francisco’s Justin Herman or Napolean III’s George-Eugène Haussmann in Paris, ruthless autocrats who used their power to level whole neighborhoods and redesign the urban fabric, and to destroy communities resistant to capitalist control.

The extension of the Panhandle to Market and Van Ness, and the addition of a half dozen radial boulevards from this city center, never came to pass. A brilliant idea for Capp Street to be a car-free “park or market-way”, centering the whole Mission-South Van Ness corridor as a central district of city life never materialized. Perhaps one of the most remarkable features of the unrealized Burnham Plan would have made Islais Creek the central natural feature of a long linear park stretching from the upper reaches of Glen Canyon all the way to the bay; today the water runs in culverts buried under the bleak interstate freeway, one of the few that overcame citizens’ opposition in the 1950s and 60s.

Several hundred copies of the Burnham Plan itself were destroyed in 1906, but a few survived to be reprinted in the early 1970s at a different juncture of public discussion over the future of the city. In an introductory essay to the new edition, James R. McCarthy speaks for the planning mentality of that era when he claims that Burnham’s focus on open and efficient roadways had been stymied but would “inevitably be implemented in some way at some time when the freeway phobia of the 60s gives way to rational unemotional evaluation of circulation needs.”

Instead of an uncontested, machine-like rationality that his comment implies, we’ve instead moved towards a more convivial and ecologically aware city since that time. Freeways have been removed, we’ve seen an enormous increase in bicycling, an ongoing expansion (or actually, re-establishment) of light rail lines, and local planning processes seek to include citizens in ways unimagined in previous eras. In spite of this, planning remains a specialized pursuit of paid professionals, either city employees or in the service of local real estate interests. Having exhausted my own limited patience in public planning processes for the citywide Bike Plan, the mid-Market Redevelopment Zone, and the Better Valencia “Great Streets” plan, the fatal shortcomings plaguing our efforts at participatory planning are too apparent. Long, poorly conducted public meetings to solicit “input” from citizens seem more like simulated performances of planning than the real thing. When some people are employed to attend public meetings while others are expected to participate in their “free time” inequitable imbalances are unavoidable. “Credible” ideas become those put forward by the monied institutions that can send professionals to meeting after meeting over years.

As a result, beyond the earnest gadflies who hang in there, most citizens tune out and find ways to shape their environments through local and direct activities. A burgeoning ecological consciousness drives these initiatives. Oldtimers and newbies alike are re-engaging with the city’s underlying nature, reclaiming open spaces for native habitat, restoring native plants on hilltops, working on restoration projects in the Presidio, fighting for the health of Lake Merced, seeking to close more of Golden Gate Park to automobiles, working in community gardens and local parks, and enlivening a bayshore that was lost to commerce for most of our city’s history. All of these efforts interact with city planning and corporate scheming to give a different shape to our future city.

Perhaps some day in the not too distant future, we’ll bring our entombed creeks and ponds back to the surface as part of a general reconnection to bay and ocean life. As I bicycle past the Water Department’s efforts to repair the sewage system near 18th and Shotwell, at the bottom of the historic lakebed, I can already imagine them undoing that work in future years as they open up Mission Creek and we build a new parkway on the long-forgotten riparian corridor that is still there, just waiting for us to reimagine and re-engineer our city with its natural features instead of against them. Burnham would approve.

I have always been intrigued by Burnham. It is difficult to reconcile the good and bad about him — the planning and design of truly beautiful places (at least in the case of Chicago, SF) against the why and “for who” behind the proposed and less often actual construction of these places.