Recent Posts

-

And Yet, We Go On

April 22, 2024

-

It IS Happening Here

February 16, 2024

-

General Ludd to General Intellect

January 11, 2024

-

Temporal and Geographic Edges

December 26, 2023

-

The Root of All Evil

October 13, 2023

-

Post-Pandemic Melancholia . . . Same As It Ever Was?

September 3, 2023

-

Chronicle of Deaths Foretold

June 24, 2023

-

Reparations is the Least We Should Do

May 11, 2023

-

We Are Not Alone

April 9, 2023

-

War and Anti-War

February 22, 2023

|

This article appeared originally in the “Dispatch” section of the East Bay Review about a week ago. It fell off the internet (!) so I am delighted to have it reposted here. My friend Elizabeth Creely is the author, and she has also been a great supporter of our organizing efforts to save the Pigeon Palace.

Real estate investors calculating profit margins on the potential purchase of the Pigeon Palace, May 5, 2015. May 5, 2015: A man driving a gleaming SUV pulled over in front of an apartment building in San Francisco and let out a long, low whistle under his breath that was almost reverent. 2840 Folsom Street, a massive Victorian painted in shades of lemon yellow and chocolate brown, had banners made of bed sheets flying from every window. “Pigeon Palace 4 Ever,” read one. Another sheet, flapping and turning in the wind, read “Affordable Housing Forever.” These banners were made by the tenants of the Pigeon Palace, so-called because of the owner’s love of the birds. The building was for sale, and eviction was in the air. The current tenants had scheduled a protest that day to forestall the sale and forewarn any interested buyer that they would fight to stay in their homes.

The man parked his SUV and got out and walked over to look at the banners more closely. He looked expensive like his car: groomed silver hair, leather driving moccasins, and jeans which had been pressed. The look was a Wealthy Normcore, a low-key rendition of unstudied, luxurious ease. He stood under one of the banners, studying it. I walked over.

“Hi there,” I said. “Are you interested in buying this building?”

He looked at me. “Uh, no,” he replied. “I’m not interested.”

“No? How did you find out about this?” I gestured with my writing pad to the building.

“I was just driving by…” His words trailed off. He was mentally quitting the scene, having barely seen anything except the banners and their upstart proclamations.

“Can I get your name?” I asked.

“No,” he answered flatly. He turned on his heel and left.

There’s money in them thar’ halls! The silver-haired man was probably lying. He was obviously there for a “walk-through”— a preliminary step in the eventual sale of a property. It had been scheduled that day by the state-appointed conservators of Frances Carati, the elderly landlord and owner of the property who had been declared incompetent to manage her own affairs a few years earlier by the county’s Adult Protective Services agency. She’s now living in a nursing home in San Francisco.

Frances’s father purchased the building in 1942 with his GI Bill for $12,000. Now it is worth at least $2 million. That’s the offer that was made by the San Francisco Community Land Trust, which had worked with the tenants of the building to purchase the Pigeon Palace. If the Land Trust’s offer had been accepted by the conservators, the tenants would have owned the building cooperatively and the Pigeon Palace would have been taken off the market. But the conservators didn’t accept the Land Trust’s offer and put the building on the auction block, citing their obligation to meet Frances Carati’s financial interests, which, they said, must be upheld. Two million wouldn’t cut it. The building must be sold and quickly. There would be more silver-haired men that day looking at the property, sizing up its dilapidated glory, balancing the cost of renovation against the profit it might produce, minus its current tenants.

Buyouts are the most common method for clearing a building. Low level harassment works, too. Real estate agents and speculators know that tenants will abandon their rights and their apartments, leaving them empty, ready for a quick coat of paint and maybe a new sink, before remerging on the rental market as a shiny dwelling available for $4,268.00, the median price of a two-bedroom apartment in the Mission District. I remember the elderly Latin American couple who lived down the street from me. The woman and I would greet each other equably on our way to the laundromat. “Hola,” we would murmur to each other in passing. One day, I noticed that the façade of their white stuccoed building was now a plastered a smooth slate-gray. The door to their apartment was gone. Under what conditions they’d been gotten rid off was anyone’s guess, but whether it was by preemptory command—you have to go now—or a buyout, the effect was the same. The couple had vanished, along with their door.

The tenants of the Pigeon Palace plan on staying put. As the silver-haired man sped away in his SUV, the tenants—Chris Carlsson, Adriana Camarena, Ed Wolf, Kirk Read, Keith Hennessy, and Carin McKay—were in their apartments, preparing to meet their friends and supporters outside to confront the buyers who wanted to buy the place.

Oscar Salinas checking out the Pigeon Manifesto. Oscar Salinas was one of the first to arrive. He stood on the sidewalk reading a flyer; this was the Pigeon Manifesto, written by the tenants. It began: “Our six-unit building is called the Pigeon Palace, after the hearty rule-defying birds loved by our dear landlord Frances Carati. But oh shit! Our home is for sale! And the vultures are circling.”

Chris Carlsson, one of the tenants, walked down the steps. “Hey, there,” he said, walking over to Salinas. “Great to see you!”

“How you doing, buddy?” replied Salinas. The two men hugged.

Ian Waisler, a former tenant, walked up, smiling. “Hi,” he said to no one in particular. He sat down on the front stoop, a burrito in hand, and began eating it.

A man carrying a saxophone arrived, and looked around. “Where is everyone?” he asked. Ofir (that was his name) was a member of the Brass Liberation Orchestra, a “multigender/multiracial/multigenerational” musical group that provides a musical soundtrack for protests. He slung the saxophone around his neck and blew a few bluesy notes.

More people started arriving. I asked one them, Thom, why he was there. He hesitated. “Well…it’s simple,” he said finally. “I’m here to save my friends’ house. It’s that basic.” He looked relieved as he told me this.

Earlier, Chris had passed out a piece of paper with questions to pose to prospective buyers. “Do you know who lives here?” was one question. “What is your goal today?” was another. And “Can you imagine not evicting tenants?” The questions were simple and provocative and read like messages on a Jenny Holzer projection, designed to intervene in a process that was supposed to be smooth, unpublicized, and uneventful.

“This isn’t what people expect when they come to buy real estate,” observed the writer Rebecca Solnit, who had strolled up from the direction of 26th Street. “So I think it’s effective. But you know”—she turned her large eyes on me—“some people can create very elaborate rationales for evicting people.”

“Do you know what structure this is gonna be?” asked Thom. “Are we gonna stand around, Critical Mass style?” It would have been appropriate. Chris Carlsson is widely credited with starting Critical Mass, the monthly bike ride through the streets of San Francisco, although he flatly denies this.

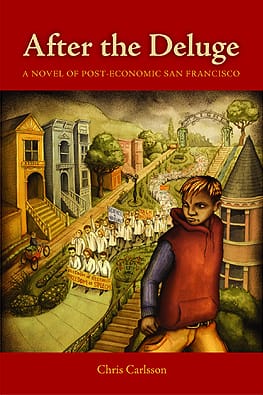

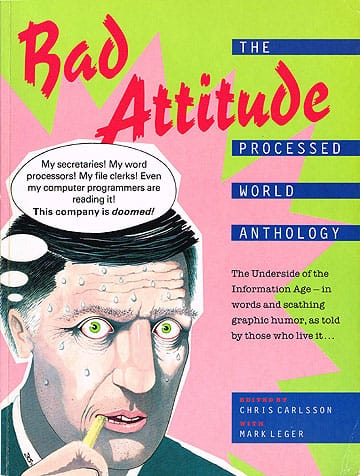

Chris is a writer and the founder of Shaping San Francisco, a history project. (“History from below” is the purpose of the organization.) Chris and his co-tenants represent the now-vanishing culture of writers, artists and activists once native to America’s big cities and now becoming increasingly rare as San Francisco and New York host an influx of the wealthy, who seem intent on privatizing everything.

Privately held properties like the Pigeon Palace are not normally thought of as public space, but the distinction gets blurry when the tenants are masterful activists like Ed Wolf, a noted AIDS activist, or Adriana Camarena, founder of Unsettlers: Migrants, Homies and Mammas, a media project that investigates and chronicles the Mission District’s historic Latin American community. The Pigeon Palace became public space because of the activities that took place there. Small conventions of all sorts and for every reason made the apartments of the Pigeon Palace a public commons. Doors were open, dinners were made, plans discussed, visions brought forth. The city was shaped in the living rooms and kitchens of Pigeon Palace. The cheap rent birthed big ideas and projects: the artists, writers and activists who live at the Palace wrote books, edited anthologies, painted gorgeous murals, fought for health care during the AIDS crisis and, generally speaking, critically reflected San Francisco’s mythic past, muddled present, and vaunted future back out to the city. In a city where renters happily fork over 50 percent of their paycheck in order to live in a city enriched by ‘culture,’ people like Chris are being shown the door, while the work they did, which gave the city its identity as interesting and provocative place to live in, is both un-remunerated and monetized every time a real estate agent or development LLC refers to “vibrancy.” Your work here is finished, is the message. Continue reading Mayday at the Pigeon Palace

by Chavell, adapted for the Pigeon Palace and the SF Community Land Trust First, a huge thanks to everyone who supported the Pigeon Palace effort. It seems that we are going to be able to stay here in our home on Folsom Street in San Francisco permanently! There are some final hurdles to overcome, but it’s looking pretty solid at the moment. By the end of summer we should be celebrating; we’ll also be dealing with organizing ourselves internally to self-manage our building, and to oversee a huge process of rehabilitation and improvement in our century-old Victorian. Our apparent victory here is already inspiring lots of other folks in San Francisco, people facing eviction as well as the thousands who are in precarious rental situations who may be able to follow this path too. We hope to be a strong source of support going forward for others to achieve similar results.

The radical class and ethnic cleansing underway in San Francisco is paralleled in many other major cities around the world competitively styling themselves neoliberal capitals. In Paris in June, I saw a city that has been gentrified for more than a century—reading David Harvey’s excellent Paris: Capital of Modernity reveals a process pursued during the Second Empire (1849-1871) by the famous urban planner Hausmann based on debt financing, spatial and social restructuring, slum clearance, road building, etc. The result was the expulsion of much of the industry that had developed in the heart of Paris, along with the new industrial working class it employed. Social classes were segregated into different districts (newly created arrondisements) while incessant rent increases fueled a great concentration of wealth and the steady impoverishment of the majority of the population. Meanwhile, new trends in merchandising (e.g., the department store), and a deliberate fostering of new fashions fueled a boom in consumerism that also stimulated the economy when it had been languishing in depression at the end of the 1840s. (It didn’t hurt that the California Gold Rush was sending lots of money into the French economy at the same time!)

Anyway, our apparent lucky “lottery win” of our home in San Francisco’s Mission District, against all odds, settles—for we few lucky ones—the terrible insecurity and uncertainty dominating most local renters’ daily lives these days. Psychologically, I can finally stop fretting about where I’m going to be, and get back to focusing on how to engage with where I am. The fact that we are part of a Land Trust means I don’t have to worry about housing values, future rent increases, or any of the usual issues that accompany either ownership or tenancy. There will be other issues to be sure, self-management is its own reward and headache (we almost jokingly put a slogan on the building “We want Headaches, Not Equity!”). But with the major fears and concerns aside, I feel my home is “enough” as it becomes a foundation from which I can pursue other interests and activities.

Maintaining our homes is one of the basic fundamentals beneath a good life. But the overarching logic of this society is focused on incessant growth, which the ideological promoters insist will eventually give everyone a good life—even though it’s perfectly apparent that the growth economy produces the opposite: a growing number of displaced and impoverished people globally, an ever wealthier few who own more and more of everything, and a planet being choked and degraded by the rapacious exploitation of every corner and every resource. For the millions working in the factories and offices of the world, work is constantly speeding up and being made more intense and taking longer (whatever happened to the 8 hour day or the 40 hour week?), while space for creativity, art, music, and self-expression, not to mention nature itself, are radically diminished.

To the dead of the 1871 Paris Commune in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery.  In the catacombs of Paris…  Another kind of death…. department stores! In the past few years a new movement has emerged under the rubric of “Degrowth,” though it sounds a lot better in French or Italian where the theoreticians have done most of the writing (décroissance or descrescita… in the Italian scene, the expression has been “decrescita feliz” or happy degrowth!). A friend suggested a better term in English might be “sufficiency” which trumps the awkward negative connotations of ‘degrowth’ and also leads our thoughts into a different direction than the much co-opted term “sustainability” (which by now seems to be about sustaining growth itself!). The French words in the title of this post, ça suffit, mean “that’s enough,” and I am very interested in developing a common political discourse that focuses on “enough-ness.”

I wrote Nowtopia a while back (published in 2008 in English, 2009 in Italian, last year in Brazilian Portuguese), which set out to describe a new politics of work, based on the common experience of people taking their time and technological know-how of out the market. When they aren’t at their paid jobs making money, they are often doing hard, worthwhile, but unpaid work. This Nowtopian work often addresses the crises of planetary ecology, social anomie, and isolation in local ways, but also allows the practitioners to engage in technological and social creativity in ways that wage-labor rarely allows for. When I traveled in Italy in 2008 with my book, I met Maurizio Pallante, author of Sustainable Happiness, and a man dedicated to the new politics of Degrowth.

Now a new book has been published in English called Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era and it’s an important contribution to rethinking politics in the 21st century (full disclosure, I wrote one of the 51 short essay/definitions in the book on “Nowtopians”). This slim volume is packed with big ideas organized into 3-page essays that define the key terms, such as Commons, Conviviality, Bioeconomics, Environmental Justice, Political Ecology, Autonomy, Commodification, Emergy, Imaginary, Happiness, and much more. But the collection doesn’t shy away from the many contradictions embodied in the emerging critique of capitalist growth—in fact many of the essays in the book directly conflict with each other, which bolsters the book’s credibility and importance in my eyes. I also appreciate that the book includes forthright critics of capitalism (such as myself) and various Degrowthers who are ambivalent about markets, money, and commodities, and some who consider these aspects of today’s world unchangeable. In another article published in 2014 in Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, called “Degrowth and Demonetization: On the Limits of a Non-Capitalist Market Economy” Andreas Exner develops a pretty thorough critique of the fantasies held by many eco-inspired radicals that there is a role for money and markets in a post-capitalist world. Going back to Pierre Joseph Proudhon, the assumption that non-capitalist money and markets could exist “blooms in the discourse on regional currencies, time banks, and local exchange trading systems (LETS)… [which] is also at the core of the ‘green money’ debates.” For Exner, “only reciprocity allows democratic governance and participatory planning.” Now a new book has been published in English called Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era and it’s an important contribution to rethinking politics in the 21st century (full disclosure, I wrote one of the 51 short essay/definitions in the book on “Nowtopians”). This slim volume is packed with big ideas organized into 3-page essays that define the key terms, such as Commons, Conviviality, Bioeconomics, Environmental Justice, Political Ecology, Autonomy, Commodification, Emergy, Imaginary, Happiness, and much more. But the collection doesn’t shy away from the many contradictions embodied in the emerging critique of capitalist growth—in fact many of the essays in the book directly conflict with each other, which bolsters the book’s credibility and importance in my eyes. I also appreciate that the book includes forthright critics of capitalism (such as myself) and various Degrowthers who are ambivalent about markets, money, and commodities, and some who consider these aspects of today’s world unchangeable. In another article published in 2014 in Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, called “Degrowth and Demonetization: On the Limits of a Non-Capitalist Market Economy” Andreas Exner develops a pretty thorough critique of the fantasies held by many eco-inspired radicals that there is a role for money and markets in a post-capitalist world. Going back to Pierre Joseph Proudhon, the assumption that non-capitalist money and markets could exist “blooms in the discourse on regional currencies, time banks, and local exchange trading systems (LETS)… [which] is also at the core of the ‘green money’ debates.” For Exner, “only reciprocity allows democratic governance and participatory planning.”

The Degrowth collection is organized by the vocabulary it seeks to insert into political debates. Many of the terms don’t immediately seem familiar. Here’s a bit of “Metabolism, societal …”

To meet the requirements of socio-economic systems such as the contemporary ones in the Global North, which operate with high economic diversity, high dependency ratios (due to a rising proportion of elderly persons and a higher average age of schooling) and high percentage-wise contribution of the service sector in the economy, it is likely that more workers and more working hours will be required to maintain the current metabolic patterns of societies as fossil fuels dwindle. This points to a contradiction with the degrowth proposal, which calls for reducing work hours (worksharing). In a future scarce in energy we will have to work more, not less. (by Alevgül H. Sorman, p. 43)

Many of us attracted to a degrowth agenda are interested also in finding an approach to both reducing work and making it fully under the control of those who do it. As the previous quote makes clear, a shrinking economy imposed (as it might be) by scarce and expensive energy will require even more work to maintain our customary comforts. But seeking an economy based on a concept of “enough” or what is sufficient for a good life, might also be possible with rather less energy and less “metabolic throughput” than we are currently using.

Continue reading Ça Suffit? Politics In the Early 21st Century

It’s no wonder so many of our romanticized utopian fantasies involve canals and bicycles… Amsterdam is in our dreams whether or not we’ve ever visited!  Ubiquitous Dutch cargo bikes, mostly used to schlep kids around… We arrived in Amsterdam to start this journey, a driving trip around France for myself, Adriana and my parents, but we start here so Adriana and I could present at the “Unofficial Histories” conference held at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. We arrived a couple of days before the conference, which gave us a chance to overcome our jet lag, and also to do some walking around town, and obligatory museum visits.

One of the many gorgeous 17th century paintings documenting the enormously self-satisfied new bourgeois at the heart of the early Dutch imperialism… We started with the Rijksmuseum, one of the world’s great collections. Having just read Russell Shorto’s excellent history of Amsterdam (“A History of the World’s Most Liberal City”), I loved doing an intensive visit of the 2nd floor’s presentation of the Dutch masters of the 16th and 17th centuries, Rembrandt and many others I’ve never heard of. But the images of the new bourgeoisie, the Dutch investors who invented the multinational corporation, who invested in the ships that opened trade with Indonesia, Africa, South America, and even established New York, are remarkable. Combined with landscapes and daily life scenes from that long-ago pre-modern era, the recording of history through these paintings is itself historically fascinating. I felt I was intensively visiting with the newly emergent/triumphant bourgeoisie of Amsterdam’s Golden Era in the early 17th century. The painters of the era brilliantly capture the self-satisfaction and confidence of the newly wealthy. There were even paintings of some of the colonial outposts in “Batavia” (Java in Indonesia), or Recife in Brazil, which do nothing to explain the attitudes of the colonists, or the deep roots of the ethnic tensions that are now percolating throughout the former imperial centers in Europe. Still, amazing to see the forts and trading posts in places that were the beginnings of today’s far-flung networks of global trade.

A pre-urbanized, pre-industrialized Holland, painted in the 1600s. Later I went over to the Amsterdam Museum to see how it presents the history of this storied city. I got a good (better) sense of the original delta/wetlands and the system of pilings on which everything sits. The evolution of the town is well-presented in the main museum; in one area a large map of the 16th century city has a series of buttons that can be pressed to bring up further images and explanations of the buildings and social activities in each area of town. The city declined during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but as the Industrial Revolution took off, Amsterdam managed to recover from its earlier loss of empire—though the city’s comfort and prosperity cannot be separated from its centuries-long exploitation of colonies in Indonesia, South America, and Africa.

Prior to entering the full museum though, visitors are shunted into an upstairs exhibit called “Amsterdam DNA” where you are prompted to use a QR code on your museum pamphlet’s back cover as a trigger for various multimedia presentations. I found the whole DNA exhibit terrible, oversimplified, and annoying. In one spot you are invited to climb on a freight bike and a video in front of you plays to show you what it was like to cycle in 1940s Amsterdam. When you ring the bell you flip the video to a contemporary view of the same streetscape. Sorry to say it was hiccup-y and kept stalling. And when it did work, it was so brief as to be meaningless. The one-room DNA exhibit tries to tell the whole history of the city in about 45 minutes, motivated by the staff’s realization that most people weren’t making it through the whole museum. So they created this gimmicky, shallow, and technology-reliant summary as a quick alternative to a more thoughtful and thorough visit to the whole museum.

A better use of technology in the main Amsterdam city museum. Each button pops up close-up images and a brief explanation.  What it looks like when you select something. I did both the DNA and the rest of the museum, and I was pretty tired by the time I finally got to the end of the chronological presentation. The fascinating story of the Provos in 1965-66 finally appeared in the last room, though I’d seen a number of crusty white bicycles in the courtyard and in a couple of spots around town, with links via QR code to an app that provides a self-guided, multimedia walking tour of Amsterdam following the locations that became famous as a result of the Provo movement. Continue reading History History Everywhere!

|

|