Recent Posts

-

And Yet, We Go On

April 22, 2024

-

It IS Happening Here

February 16, 2024

-

General Ludd to General Intellect

January 11, 2024

-

Temporal and Geographic Edges

December 26, 2023

-

The Root of All Evil

October 13, 2023

-

Post-Pandemic Melancholia . . . Same As It Ever Was?

September 3, 2023

-

Chronicle of Deaths Foretold

June 24, 2023

-

Reparations is the Least We Should Do

May 11, 2023

-

We Are Not Alone

April 9, 2023

-

War and Anti-War

February 22, 2023

|

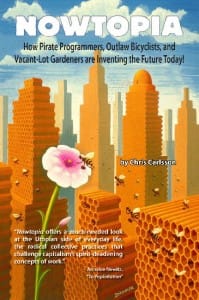

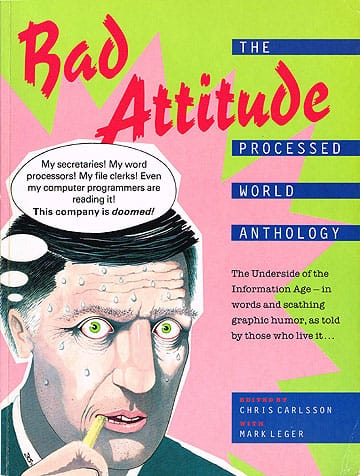

From a birthday hike on Tomales Point, elk watering at a pond with Bodega Bay and Sonoma county coast in distance across mouth of Tomales Bay. The title of this essay is an old slogan I came up with in the early 1990s, back in the days we were founding such disparate “organizations” as the Committee for Full Enjoyment (not Full Employment) and the Union of Time Thieves Local 00. It was in the context of the last years of Processed World magazine, which was published from 1981 until 1994, always shining a bright light on the insipid pointlessness of daily life on the job across corporate and nonprofit and educational America, especially in the newly emerging high-tech offices of the era. Talking about work has always felt like going public with a terrible secret, revealing a closeted awareness that the emperor has no clothes, that work as we know it is largely a waste of time if not actually making the world much worse for the doing.

For many years it seemed that few others would take up this topic, and if so, only from the point of view of rather traditional leftist frameworks. So we have had endless campaigns promoting “jobs” as something we should be in favor of, fighting to bolster palpably corrupt or inept trade unions, and a basic acceptance of the notion that economic growth is good and capitalist profits benefit the whole society. Leftists even to this day will argue that workers just need to be reminded that they are part of the mighty Working Class, and that with this reinforced consciousness, radical social change will naturally follow. In light of the moribund ideologies surrounding conversations about work and workers, it’s hardly surprising that neoliberalism’s emphasis on individual “freedom” and self-organized entrepreneurialism have influenced more people’s daily practices than anything on offer from the “left.”

Given the desultory state of critical thinking on the left with regard to work and economy, it is gratifying that some new books have finally begun to appear that challenge this situation. The four writings I’m going to weave into this piece share a certain despair at their core, but I think despair is a pretty reasonable state of mind facing our predicament. And I don’t think despair means paralysis, nor is it that old bogeyman “defeatism.” We have to hit bottom before we can start back up again to something fresh that can shake off the doldrums and stodgy stasis of revolutionary thought.

It has been almost two years since I last took up this topic on this blog. I brought in some of the new writings at that time that inspired me, from Miya Tokumitsu’s cogent critique of the bait-and-switch promise hidden in advice to “Do What You Love,” to Kathi Weeks’ The Problem with Work, both of which get referenced in a couple of the works I cite here. The new books I just plowed through for this are Cyber-Proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex by Nick Dyer-Witheford, The Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself by Peter Fleming, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, and lastly a long essay in End Notes #4 called “A History of Separation: the Rise and Fall of the Workers Movement 1883-1982”. It has been almost two years since I last took up this topic on this blog. I brought in some of the new writings at that time that inspired me, from Miya Tokumitsu’s cogent critique of the bait-and-switch promise hidden in advice to “Do What You Love,” to Kathi Weeks’ The Problem with Work, both of which get referenced in a couple of the works I cite here. The new books I just plowed through for this are Cyber-Proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex by Nick Dyer-Witheford, The Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself by Peter Fleming, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, and lastly a long essay in End Notes #4 called “A History of Separation: the Rise and Fall of the Workers Movement 1883-1982”.

Taken together these writings help define the predicament we face, which is not easily summarized in a soundbite or even two. The century-long effort to promote workers organization, most prominently in the socialist, communist, and anarchist movements that arose in the late 19th century, depended on assumptions which have not been deeply challenged in a very long time. The comrades from End Notes face it in their essay, concluding that rather than an emerging collective consciousness based on a shared experience of work as predicted by everyone from Marx onwards, “atomization won out over collectivization.” They anchor this self-evident truth in a challenge to the theoretically suspect assumption that Marx shared with the 2nd International’s Karl Kautsky and the Bolshevik Leon Trotsky: “to achieve the abolition of the proletariat, it is first necessary that each individual be reduced to a proletarian. The universalization of this form of domination is the precursor to the end of domination.” But that rosy expectation has been shattered by the actual evolution of modern life. In the early 21st century, End Notes understands that working people still produce the world we inhabit: Taken together these writings help define the predicament we face, which is not easily summarized in a soundbite or even two. The century-long effort to promote workers organization, most prominently in the socialist, communist, and anarchist movements that arose in the late 19th century, depended on assumptions which have not been deeply challenged in a very long time. The comrades from End Notes face it in their essay, concluding that rather than an emerging collective consciousness based on a shared experience of work as predicted by everyone from Marx onwards, “atomization won out over collectivization.” They anchor this self-evident truth in a challenge to the theoretically suspect assumption that Marx shared with the 2nd International’s Karl Kautsky and the Bolshevik Leon Trotsky: “to achieve the abolition of the proletariat, it is first necessary that each individual be reduced to a proletarian. The universalization of this form of domination is the precursor to the end of domination.” But that rosy expectation has been shattered by the actual evolution of modern life. In the early 21st century, End Notes understands that working people still produce the world we inhabit:

Society is still the product of all these working people: who grow and distribute food, who extract minerals from the earth, who make clothes, cars, and computers, who care for the old and the infirm, and so on. But the glue that holds them together is not an ever more conscious social solidarity. On the contrary, the glue that holds them together is the price mechanism. The market is the material human community. It unites us, but only in separation, only in and through the competition of one with all. (p. 160) Society is still the product of all these working people: who grow and distribute food, who extract minerals from the earth, who make clothes, cars, and computers, who care for the old and the infirm, and so on. But the glue that holds them together is not an ever more conscious social solidarity. On the contrary, the glue that holds them together is the price mechanism. The market is the material human community. It unites us, but only in separation, only in and through the competition of one with all. (p. 160)

Our atomized, hyper-individualized world, which we experience as being shaped by forces beyond our control, is far from a world where working-class community, or much of any other kind of community, provides a safe haven, or a meaningful daily life. We are on our own.

At present, workers name the enemy they face in different ways: as bad banks and corrupt politicians, as the greedy 1%. These are, however, only foreshortened critiques of an immense and terrible reality. Ours is a society of strangers, engaged in a complex set of interactions. There is no one, no group or class, who controls these interactions. Instead, our blind dance is coordinated impersonally through markets. The language we speak—by means of which we call out to one another, in this darkness—is the language of prices. It is not the only language we can hear, but it is the loudest. This is the community of capital. (p. 166)

Clearly a despairing analysis. Workers employ populist rhetoric to try to understand what they’re up against, but the very language and conceptual universe in which we are enveloped locks us into a “community” that is founded on our exploitation. Still, work remains at the (vulnerable, fragile) heart of capital. Similar to how we relate to cancer, we rely on language to understand work as a personal predicament rather than a social phenomenon, rather than an outcome of socially constructed choices and shared effort. But the antipathy to understanding work socially started long ago. It parallels the steady diminishment of taking pride in work, that intensified during the height of Fordist factory work when anyone with a brain found it boring and unfulfilling. The deindustrialization of the past decades is not the cause of the collapse of working class identities, but rather an accelerant for the social atomization that was already underway.

In Inventing the Future¸ Srnicek and Williams recognize that the historic left’s dependence on the industrial working class as its frame of reference has been outflanked by historical developments, not the least of which happened within the working class itself. In Inventing the Future¸ Srnicek and Williams recognize that the historic left’s dependence on the industrial working class as its frame of reference has been outflanked by historical developments, not the least of which happened within the working class itself.

For the left at least, an analysis premised on the industrial working class was a powerful way to interpret the totality of social and economic relations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thereby articulating clear strategic objectives. Yet the history of the global left over the course of the twentieth century attests to the ways in which this analysis failed to attend to both the range of possible liberating struggles (based in gender, race, or sexuality) and the ability of capitalism to restructure itself—through the creation of the welfare state, or the neoliberal transformations of the global economy. Today, the old models often falter in the face of new problems; we lose the capacity to understand our position in history and in the world at large. (p. 14)

The ideas that the working class is the motor of history, or that class struggle follows a teleological trajectory towards human liberation, are harder to believe in now. The evidence of a century of war, barbarism, modernization, and radical technological and social change does not seem to have brought us much closer to revolution. Still, trying to make sense of the complicated relationship between our own labor and the world that confronts us is at the heart of our predicament. Reclaiming the concept of “proletariat” before we dump out the rubbish bin of history is a helpful step, and each of these writings does that in their own ways.

Continue reading Start Talks Now on Work Reduction!

Mary Brown… about to say…. “Well, no…” My good friend Mary Brown died about ten days ago. Yesterday, Saturday December 19, 2015, there was a stirring memorial for her, attended by well over 200 of her friends and family, all inspirations to her while she lived. But as the grief poured out and the memories piled up, the charming and hilarious anecdotes, the horrible sense of loss, and the powerful presence she had in her absence, the overwhelming inspiration she gave us all was the lasting impression for me. Over the years she had developed her own sensibilities, her own unique ways of thinking about and engaging with the world around her. Her work, from the push to establish the bike lanes on Valencia Street and help begin the still overdue transformation of San Francisco’s urban space, to her graduate thesis on the how automobility and congestion were imposed by motordom on the Mission, to her recent work to uncover the surprising diversity in the ticky-tack architecture of the Sunset district, all embodied and modeled a deeply observant and perpetually curious relationship to San Francisco, the Bay Area, and California.

In February at the PPIE100 opening at the Palace of Fine Arts: LisaRuth Elliott, Mary Brown, Elizabeth Creely, and yours truly. I didn’t share the personal intimacies that so many memorialists did yesterday, especially her many housemates in the 22nd Street co-op. But the quirky, messy, prickly, funny, spontaneous, goofy, wonderful Mary that I have known since the mid-1990s was only confirmed and augmented by their stories. I was supposed to open the second part of the memorial of open-mic tributes, but after the lengthy ceremony and ensuing potluck, it seemed inappropriate to go back to microphone-and-audience, and anyway, we were hosting our big annual Posada party at home, scheduled long before this sad event became necessary. So I didn’t get to speak to the assembled mourners, but what I was prepared to talk about is this:

I didn’t live with Mary or even spend that much time alone with her over the years. What we shared more than anything was a mutual love of the City, an enthusiasm for exploration and meandering, for the dérive, the serendipitous, the historic mysteries embedded in the landscape—often in plain view. We both worked directly and indirectly to bring about a reinhabitation of the urban environment. We also shared a prickly contrarian sensibility that brooked no spiritual mumbo-jumbo, that took in the world through an assiduously secular lens that nevertheless could appreciate the wonder of life, the astonishing capacity of humans to connect with each other and the world around them. Mary was always a pillar of empathy and curiosity, far more capable of occupying an open-minded space of welcoming conviviality than most people I’ve ever met. At the same time she had little patience for trivialities, for niceties, for the blather that fills up way too much of our lives.

Beyond the specifics of her many accomplishments, her many friendships, and her infectious pleasure in living, I think Mary’s biggest contribution, one that is far from over, was her ability to model and share a new way of seeing the world around us. Perhaps she didn’t invent it, but as part of a wider stream of people who have been engaged in reconnecting us to place, to landscape, to the built environment, to the historic social movements that shaped our world, Mary Brown will always be with us because she helped change how we think. Never one to browbeat or lecture she still managed to convey a deeper way of seeing our world that once experienced, simultaneously humanized and naturalized each one of us. By sharing with us a utopian impulse that lacked the demanding perfectionism implied by the idea of utopia, her contribution to our changing epistemology is inestimable for those of us lucky enough to have been her friend and to have accompanied her on her perambulations across our fair town.

Mary Brown, you suffered way too much in your life, but now that it’s over it pales compared to the joy you took in the everyday pleasures right in front of us. On a StoryCorps interview with her from last June when Laura Lent asks her if she has any advice for the rest of us contemplating the unimaginable idea of a world without her, she laughs and assures us she has “lots of advice—for everyone!”… and her first, most urgent suggestion is to quit your job!

Life is far too short. When I turned 45, almost 14 years ago now, I felt that weight of mortality, how fleeting our time is on earth. To lose Mary at only 46 years of age, a life that endured four cancers over 20 years, is to know that most of us have not lived to our fullest, have not drunk nearly deeply enough of the joys and pleasures that are all around us. Mary, more than most people, showed us how to do it, and on her way out, took the time to wag her finger once more in her gently insistent way. “Do what matters! Don’t wait til later! Get on with it!” And so we should.

Mary and Adriana during the walk to Bayview Hill on February 6, 2010  On Bayview Hill Feb. 6 2010.  On the stairs at 20th and Sanchez, Feb. 5 2006 birthday walk…  Riding along the Carquinez Straits in summer 2014.  another view of Carquinez straits ride Continue reading Mary Brown Has Died But She Lives On in All of Us

Sidewalk Party October 10, 2015, celebrating the successful purchase of the Pigeon Palace by the San Francisco Community Land Trust (closed Sept. 10, 2015). As a resident of San Francisco’s latest Community Land Trust property—the Pigeon Palace—I am enjoying the new peace of mind that comes from knowing that I will never be evicted from my home. I’ve been happily surprised to feel a subtle shift in my experience of daily life–I hadn’t realized how much I was preparing to leave until I was certain that I wouldn’t be forced out.

Over the past weeks I’ve enjoyed a number of very San Franciscan moments, from the annual SOMARTS opening party of the Day of the Dead altars, our own sidewalk celebration party, to bumping into a stream of friends while on my daily walks across the City. I’ve realized that we’re still here and we don’t have to leave. I’m here for the long haul, and with it comes both possibilities and responsibilities. I’m readier than ever to dig in and make this place truly ours.

Our building has had cheap rents and it is precisely these cheap rents that gave the tenants the safe and stable foundation that allowed us all to contribute so much to San Francisco’s cultural and political life for the past several decades. A low cost of housing is an essential foundation for a full life.

These days, everyone is bombarded by the hype to “do what you love,” and supposedly if you stick to it, the money will follow. Actually, probably not. Most of us have to get the proverbial “day job,” selling a money-making skill to someone willing to buy it. If we’re lucky we make enough money in few enough hours to leave us time to do what we really care about in our “free” time.

In my early 20s I realized that I wasn’t interested in following the normal paths that this society lays out before one. I wasn’t interested in a “career” and making money held no interest for me. I saw myself as a revolutionary and wanted to participate in creating a new way to live, not just for me as an individual, but a full-blown reorganization of everyday life itself. Even then I knew my revolutionary aspirations would probably not be met, so though I’ve continued to pursue that agenda in my own unique way, I also vowed to make sure that I lived the highest quality life I could manage. The key to that was to hold down my regular costs (transit, housing, food, communications, etc.) so that I would have less pressure to “slave away for the man!” In other words, I was way too busy to have a job! The best way I could carry out my self-directed activities (which have always kept me quite busy) was to bicycle instead of owning a car, to eat local and fresh from farmer’s markets and coop stores instead of eating out, and most crucially, to find and hold on to the lowest cost housing I could manage. Not having to make many thousands of dollars every month to be able to pass a large portion over to a landlord or bank gave me something far better than money; I have time, time that is not for sale. “Free” time is unmeasurable “wealth.” Cooperation, mutual aid, solidarity, and imagination all flourish in the absence of economic coercion. Happily, this dovetailed perfectly with my evolving sense of what a revolution might consist of.

Most people haven’t made the same choices that I have, and for many, it is nearly impossible to do so. My parents weren’t wealthy when I left home at age 17, but by the time I was in my 30s they were fairly affluent, and always ready and willing to back me up if I needed it. (I never really needed that backup, but having it available is clearly a big deal.) My chosen path to avoid economic coercion at all costs has given me a lot of freedom, and led to a lot of creative output over the years. But most people are trapped in poverty, or if they are “middle class” (as most people tend to think of themselves) the ball-and-chain of car ownership, the almost inevitable accumulation of student debt, and during the past twenty years radically rising housing costs, have entrapped most people in one type of debt or another. Burgeoning homelessness puts relentless pressure on those “lucky” enough to have an abode. Pay your rent, pay your mortgage, or else. After steadily rising housing costs in the last quarter of the 20th century, the 21st century saw an unprecedented transformation. Housing costs for renters and buyers alike skyrocketed in major cities across the planet, outracing stagnant incomes and becoming a primary conduit for transferring wealth from the majority of working people into the hands of a tiny financial elite.

Every apartment that is still rent-controlled, where long-term tenants pay less than $1000 per month per person (and sometimes much less!), has become a front line in the current battlefield of class war. Our fight to save our homes in the Pigeon Palace represents a victorious skirmish, and temporary reprieve for us, but so far, it is not going to be a working solution for many people.

The Pigeon Palace Story The Pigeon Palace Story

At 83 our former landlady, who gave each of us very cheap rents because she didn’t believe in “choking people,” has been warehoused in a nursing home and denied any right of return to her home. A serious hoarder who was starting to lose her short-term memory and her mobility, but remained lucid and fiercely committed to her independence, she was declared incompetent by a judge and then relocated against her will by a court-appointed Conservator.

To save our homes we established a low-income, nonprofit housing co-op called Pigeon Palace, Inc. The San Francisco Community Land Trust (SFCLT), our political and economic partner (and benefactor) purchased the building in early September 2015 with loans from a private bank, the Mayor’s Office of Housing, and private investors including the tenants and our friends. With this purchase, we have taken the building off the market forever. But it came at a steep price that has saddled this effort with nearly $4 million in debt, a reality that casts a pall over our project and makes this a dubious model for widespread adoption or replication.

How did we manage to do this? The Pigeon Palace tenants joined with the San Francisco Community Land Trust (SFCLT) to “save” our building from the speculative real estate vultures that were hungrily circling our century-old 6-unit Victorian on Folsom Street in the heart of the Mission. The SFCLT won a probate auction, outlasting and outbidding one of the worst serial evictors in town. The Pigeon Palace was purchased at the height of the market for an absurdly high price. Our story, while inspiring on the face of it, sadly represents many of the worst contradictions that dominate the politics of housing not just in San Francisco but in every desirable city in the world.

Continue reading Forget Affordability: In Defense of Cheap Rent!

|

|

It has been almost two years since I last took up this topic on this blog. I brought in some of the new writings at that time that inspired me, from Miya Tokumitsu’s cogent critique of the bait-and-switch promise hidden in advice to “Do What You Love,” to Kathi Weeks’ The Problem with Work, both of which get referenced in a couple of the works I cite here. The new books I just plowed through for this are Cyber-Proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex by Nick Dyer-Witheford, The Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself by Peter Fleming, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, and lastly a long essay in End Notes #4 called “A History of Separation: the Rise and Fall of the Workers Movement 1883-1982”.

It has been almost two years since I last took up this topic on this blog. I brought in some of the new writings at that time that inspired me, from Miya Tokumitsu’s cogent critique of the bait-and-switch promise hidden in advice to “Do What You Love,” to Kathi Weeks’ The Problem with Work, both of which get referenced in a couple of the works I cite here. The new books I just plowed through for this are Cyber-Proletariat: Global Labour in the Digital Vortex by Nick Dyer-Witheford, The Mythology of Work: How Capitalism Persists Despite Itself by Peter Fleming, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, and lastly a long essay in End Notes #4 called “A History of Separation: the Rise and Fall of the Workers Movement 1883-1982”. Taken together these writings help define the predicament we face, which is not easily summarized in a soundbite or even two. The century-long effort to promote workers organization, most prominently in the socialist, communist, and anarchist movements that arose in the late 19th century, depended on assumptions which have not been deeply challenged in a very long time. The comrades from End Notes face it in their essay, concluding that rather than an emerging collective consciousness based on a shared experience of work as predicted by everyone from Marx onwards, “atomization won out over collectivization.” They anchor this self-evident truth in a challenge to the theoretically suspect assumption that Marx shared with the 2nd International’s Karl Kautsky and the Bolshevik Leon Trotsky: “to achieve the abolition of the proletariat, it is first necessary that each individual be reduced to a proletarian. The universalization of this form of domination is the precursor to the end of domination.” But that rosy expectation has been shattered by the actual evolution of modern life. In the early 21st century, End Notes understands that working people still produce the world we inhabit:

Taken together these writings help define the predicament we face, which is not easily summarized in a soundbite or even two. The century-long effort to promote workers organization, most prominently in the socialist, communist, and anarchist movements that arose in the late 19th century, depended on assumptions which have not been deeply challenged in a very long time. The comrades from End Notes face it in their essay, concluding that rather than an emerging collective consciousness based on a shared experience of work as predicted by everyone from Marx onwards, “atomization won out over collectivization.” They anchor this self-evident truth in a challenge to the theoretically suspect assumption that Marx shared with the 2nd International’s Karl Kautsky and the Bolshevik Leon Trotsky: “to achieve the abolition of the proletariat, it is first necessary that each individual be reduced to a proletarian. The universalization of this form of domination is the precursor to the end of domination.” But that rosy expectation has been shattered by the actual evolution of modern life. In the early 21st century, End Notes understands that working people still produce the world we inhabit:Society is still the product of all these working people: who grow and distribute food, who extract minerals from the earth, who make clothes, cars, and computers, who care for the old and the infirm, and so on. But the glue that holds them together is not an ever more conscious social solidarity. On the contrary, the glue that holds them together is the price mechanism. The market is the material human community. It unites us, but only in separation, only in and through the competition of one with all. (p. 160)

In Inventing the Future¸ Srnicek and Williams recognize that the historic left’s dependence on the industrial working class as its frame of reference has been outflanked by historical developments, not the least of which happened within the working class itself.

In Inventing the Future¸ Srnicek and Williams recognize that the historic left’s dependence on the industrial working class as its frame of reference has been outflanked by historical developments, not the least of which happened within the working class itself.