Recent Posts

-

And Yet, We Go On

April 22, 2024

-

It IS Happening Here

February 16, 2024

-

General Ludd to General Intellect

January 11, 2024

-

Temporal and Geographic Edges

December 26, 2023

-

The Root of All Evil

October 13, 2023

-

Post-Pandemic Melancholia . . . Same As It Ever Was?

September 3, 2023

-

Chronicle of Deaths Foretold

June 24, 2023

-

Reparations is the Least We Should Do

May 11, 2023

-

We Are Not Alone

April 9, 2023

-

War and Anti-War

February 22, 2023

|

April 3, 2016, giving this talk in Santiago, Chile at the 5th Forum Mundial de Bicicleta We have come together in our shared enthusiasm for bicycling. At one time or another in our lives, each of us came to identify bicycling as the key to social change. Or we concluded it was the key to unraveling the dangerous traffic nightmare plaguing most of the world’s cities, or to reclaiming a more convivial public space from the domination of private cars. Or we connected bicycling to a refusal to participate in oil wars; or a refusal to accept the mountain of debt associated with car and oil dependency; or a refusal of the massive pollution by fossil fuels that is wreaking havoc with the world’s climate.

On a simple level, most of us learned to bicycle when we were children, and quickly discovered that bicycling unlocked nearby streets and neighborhoods, and eventually entire cities that we could reach by riding our bikes. Personal mobility, a freedom to move independently through space, is an intoxicating pleasure and is a right of all humans, or should be.

This freedom of mobility has been thoroughly colonized by the marketing engineers of the automobile industry for more than 100 years. Bicycling lost the argument in the early 20th century, an argument that bicycling itself had started with demands for good roads covered in asphalt in the late 19th century. As cars came to dominate personal transportation, displacing walking, bicycling, and streetcars and having streets widened and reorganized to accommodate faster speeds and more parking, bicycling was redefined as a child’s first vehicle on their way to a mature embrace of the car in adulthood. Most people across the planet have been convinced to accept this, or at least they were until about a generation ago.

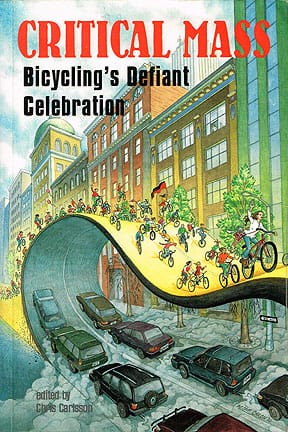

Starting in 1992 in San Francisco, Critical Mass emerged as a monthly “organized coincidence” in which first dozens, then hundreds, and eventually thousands of bicyclists took to the streets to “ride home together.” While cars clogging our streets in endless daily traffic jams is treated as inevitable and natural, part of the unavoidable “weather” of city life, dense masses of bicyclists are anomalous, some kind of strange unnatural aberration, an unexpected emergence of rebellious creativity. Though we always said “we aren’t blocking traffic, we ARE traffic!” most participants, bystanders, and motorists understood that this was something more than mere traffic. I like to say it was a Defiant Celebration. We discovered that by bicycling together in a celebratory mass seizure of the roads we were cracking open the closed public space of city streets, reclaiming it from the decades-long enclosure of our thoroughfares by the forces of “motordom” and their successful marginalization of other transit options. We also opened a self-governed space free of commerce, where coming together in conversation and shared activity was a natural experience not requiring permission, licenses, or the purchase of products.

Since that auspicious turn a generation ago, bicycling has returned to the world’s cities in a way no one could have predicted. Picking up enthusiasm from a wide swath of the population, literally hundreds of thousands of people are bicycling every day now instead of driving in cars. This is an amazing outcome of a slowly snowballing collective decision to change life that started small in one place, then spread to other places, and eventually led to millions of people in hundreds of the world’s cities changing their everyday behavior.

Continue reading If Bicycling is the Key, What Does it Unlock?

April 3, 2016, giving this talk in Santiago, Chile at the 5th Forum Mundial de Bicicleta Nos hemos reunido en nuestro entusiasmo compartido para el ciclismo. En uno u otro momento de nuestras vidas, cada uno de nosotros llegó a identificar el ciclismo como la clave para el cambio social. O llegamos a la conclusión de que era la clave para desenmarañar la pesadilla de tráfico peligroso que atormenta a la mayoría de las ciudades del mundo, o para recuperar un espacio público más agradable de la dominación de los automóviles privados. O conectamos al ciclismo a nuestro rechazo de participar en las guerras del petróleo o la montaña de deuda asociada con la dependencia al automóvil y el petróleo; o un rechazo a la contaminación masiva por combustibles fósiles que está causando estragos en el clima del mundo.

En un primer nivel, la mayoría de nosotros aprendió a montar bicicleta cuando éramos niños, y pronto descubrió que el andar en bicicleta duba acceso cercanas calles y barrios, y finalmente ciudades enteras que podíamos alcanzar al andar en nuestras bicis. La movilidad personal: la libertad de moverse de forma independiente a través del espacio es un placer embriagante y es un derecho de todos los seres humanos, o debería serlo.

Esta libertad de la movilidad ha sido completamente colonizada por los ingenieros de la mercado tecnia de la industria automotriz durante más de cien años. La bicicleta perdió el argumento a principios del siglo veinte, un argumento que el ciclismo en sí había comenzado en el siglo 19 con demandas de buenos caminos cubiertos de asfalto. En la medida que los automóviles llegaron a dominar el transporte personal, desplazando la movilidad a pie, en bicicleta y en los tranvías, y con la ampliación y reorganización de las calles para acomodar velocidades más rápidas y más aparcamiento, el ciclismo fue redefinido como el primer vehículo de un niño en su camino a un maduro abrazo del coche en la edad adulta. La mayoría de la gente en todo el planeta estaba convencido de esto, o al menos lo estaban hasta hace una generación.

A partir de 1992 en San Francisco, la masa crítica surgió como una mensual “coincidencia organizada” en que primero decenas, luego centenares y finalmente miles de ciclistas salieron a las calles para “andar juntos de regreso a casa.” Mientras que se ve como inevitable y natural que los automóviles atasquen a diario a nuestras calles en interminables nudos de tráfico, como parte inextricable del “clima” de la ciudad, a las masas densas de ciclistas se les define como anómalas, algún tipo de extraña aberración antinatural o una inesperada aparición de creatividad rebelde. Aunque siempre decimos: “No estamos bloqueando el tráfico, ¡SOMOS TRÁFICO!”, la mayoría de los participantes, los transeúntes y los automovilistas entendieron que esto era algo más que mero tráfico. Me gusta decir que fue una Celebración Desafiante. Descubrimos que por andar en bicicleta juntos en una toma festiva de las calles estábamos abriendo grietas en el espacio público cerrado de las calles de la ciudad, reclamando nuestras arterias de las décadas de encierro a causa de la dominación del motor y su éxito en marginar otras opciones de transporte. También hemos abierto un espacio autónomo, libre de comercio, donde reunirse en conversación y actividad común es una experiencia natural que no requiere de permisos, licencias, o la compra de productos.

With Andreas Rohl (left) and Rodrigo Diaz (right), with moderator Sergio Corrales (far right) Desde ese auspicioso giro hace una generación, el ciclismo ha regresado a las ciudades del mundo en una manera que nadie podría haber predicho. Acogió el entusiasmo de una amplia franja de la población; existen literalmente cientos de miles de personas andando cada día en bicicleta en vez de conduciendo autos. Este es un increíble resultado de una decisión colectiva para cambiar la vida que lentamente hizo cúmulo en un lugar pequeño, luego se extendió a otros lugares, y eventualmente condujo a millones de personas en cientos de ciudades del mundo a cambiar su comportamiento cotidiano.

Continue reading Si el ciclismo es la clave, ¿qué nos revela?

Havana It’s an elusive concept. As many have by now pointed out, for many people it’s easier to imagine the end of the planet than the end of capitalism. The success of neoliberalism since the mid-1970s at colonizing political imagination is remarkable to say the least. Still, as the writings I examined in the previous entry and the new book by the excellent journalist and historian Paul Mason all demonstrate, new ideas are percolating, and the end of capitalism is inevitable, even if we’re pretty unclear on what comes next.

Curiously I am sitting in Santiago, Chile writing this but not long ago I was able to visit a place where a strange version of post-capitalism is still trying to exist. In Cuba housing is nearly completely decommodified (no one pays rent and until quite recently no one could buy or sell their homes, only trade them straight up), medical care is completely decommodified, and education is too. (Here in Chile a massive student movement helped propel President Bachelet back into power—a centrist social democrat, somewhat left by post-dictatorship Chilean standards—promising to make public higher education free and available to all.) Funny that Obama went to Cuba to promote trade at a moment when so much of the world economy is sputtering at best, and teetering on the brink of another great unraveling. Fidel Castro published an open letter repudiating Obama’s “happy face” call to forget the past and focus on the future. This willful amnesia is a quintessentially American quality that has served Obama very well during his presidency. He has repeatedly insisted on looking forward in order to reinforce a culture of complete impunity for war criminals and financial criminals and one must assume, assuring his own financial well-being long after his presidency.

Havana  Attempting to untangle the dark history of the Castros’ “communism” from a more radical point of view has been done elsewhere, but seeing the results in 2016 had the effect of peeling back layers of forgotten history. In his amazing novel The Man Who Loved Dogs, Cuban novelist Leonardo Padura whips back and forth between Cuba in the 1970s, 1980s, the hungry Special Period of the early 1990s, and into the 2000s, juxtaposing it all to the story of Trotsky in exile, first in Siberia, then on an island in the Bosporus Straits in Turkey, then Norway, before finally arriving to Coyoacan in Mexico. In the novel the Stalinists of the Spanish Communist Party are portrayed as fanatical zealots who destroy the Republican cause from within and select Ramon Mercader to be specially trained as Trotsky’s assassin. The man who loves dogs could be seen as Trotsky, but it becomes clear that it is Mercader himself who as an elderly dying exile on a Cuban beach (after serving 20 years in a Mexican jail and another decade in an upscale apartment in Moscow as a “hero of the revolution” for his sordid deed) slowly recounts his story to the disillusioned and demoralized Cuban writer who tells the story within the story. It’s an amazing book, serving as an allegory on the failure of 20th century revolutions in general, and as an exemplary tale of fear, betrayal, fanaticism, obedience, and self-loathing which turn out to be at the heart of much of the Communist movement of the 20th century, dominated by the insanity of Stalin, and later Mao, and even the Castro brothers who fully embraced the Stalinist police state model. Attempting to untangle the dark history of the Castros’ “communism” from a more radical point of view has been done elsewhere, but seeing the results in 2016 had the effect of peeling back layers of forgotten history. In his amazing novel The Man Who Loved Dogs, Cuban novelist Leonardo Padura whips back and forth between Cuba in the 1970s, 1980s, the hungry Special Period of the early 1990s, and into the 2000s, juxtaposing it all to the story of Trotsky in exile, first in Siberia, then on an island in the Bosporus Straits in Turkey, then Norway, before finally arriving to Coyoacan in Mexico. In the novel the Stalinists of the Spanish Communist Party are portrayed as fanatical zealots who destroy the Republican cause from within and select Ramon Mercader to be specially trained as Trotsky’s assassin. The man who loves dogs could be seen as Trotsky, but it becomes clear that it is Mercader himself who as an elderly dying exile on a Cuban beach (after serving 20 years in a Mexican jail and another decade in an upscale apartment in Moscow as a “hero of the revolution” for his sordid deed) slowly recounts his story to the disillusioned and demoralized Cuban writer who tells the story within the story. It’s an amazing book, serving as an allegory on the failure of 20th century revolutions in general, and as an exemplary tale of fear, betrayal, fanaticism, obedience, and self-loathing which turn out to be at the heart of much of the Communist movement of the 20th century, dominated by the insanity of Stalin, and later Mao, and even the Castro brothers who fully embraced the Stalinist police state model.

Getting a signal outside of Hemingway’s storied Floridita Bar in Havana… So post-capitalism! Turns out the Stalinists weren’t capable of bringing down capitalism and only managed to create strange pockets of police state corporatism, a rather worse outcome among dozens of possibilities one might imagine. Nowadays, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the full integration of China into the world capitalist system have left very few places outside the orbit of markets and money. North Korea perhaps, though it is hardly a beacon of alternativism and inspiration! Cuba on the other hand is at an interesting juncture, and could possibly change in ways that do inspire and provoke beyond its own borders. But lessening the grip of the state, not to market forces so much as to the initiatives and activities of its own citizenry, is an essential step. After 60 years of a one-party state it may be difficult for most Cubans to take independent action. The recent years’ opening to allow people to rent rooms, start small restaurants, etc., has led to a boom in tourism that the country’s infrastructure (transportation especially) can barely handle, and a lot of foreign investors wanting to get in for the expected take-off of hotels, condominiums, real estate, and so on. For Cubans, in spite of the decommodification of key elements of life, the monthly salary of a little over $20 does not suffice, and nearly everyone is trying to get a piece of the tourist action, where the convertible peso is used (e.g. a couple of taxi rides in Havana cost the same as a Cuban’s monthly salary!). Most people looking at Cuba today see a country on the road to a more complete integration into world economic activity and with it a further monetization of Cubans’ daily lives. It’s very hard to imagine a Stalinist state changing its DNA to allow for a radical confederation of workers coops to self-manage the complex transition to an unknown relationship to the world market. The most likely model is China, where the state is the final arbiter (and guarantor) of all economic investments and makes all the main decisions. Ultimately everyone works for the State, Inc., and the accumulation of capital is a key element in that process, depending on wage-labor as the primary social relationship.

Continue reading Thinking about Post-Capitalism

|

|

Attempting to untangle the dark history of the Castros’ “communism” from a more radical point of view has been

Attempting to untangle the dark history of the Castros’ “communism” from a more radical point of view has been