Just after finishing the delivery of my Talk in Spanish, following Olatunji Oboi Reed of Equiticity, who opened…

I had a great time in Lima, Peru at the 7th annual World Bike Forum (Forum Mundial de Bicicleta #FMB7). It’s nothing like VeloCity or any bicycle industry conference, though apparently it does have something in common with the North American BikeBike conference that I’ve never been to. It takes place over 4 days with all-day meetings and workshops each day, with a kind of Critical Mass at the end of most days. We also had a famous cumbia band, Los Mirlos, who played opening night to a small audience in the stadium where we held the event, starting with a new song about bicycling they’d just written in collaboration with a number of attendees. The FMB is very grassroots, nearly everyone who comes is involved in some kind of nonprofit organization or volunteer advocacy group, with plenty of aficionados of touring, mountain biking, BMXing, and other forms of bicycle specialization. It is also extremely middle and upper-middle class, as it has been at all the prior gatherings, starting in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 2012 and going to Curitiba, Medellin, Santiago, and Mexico City before landing in Lima this year (and Quito next year where the theme is “Mingamos el Mundo!”) There are a smattering of government representatives too, usually folks from various urban transit agencies operating with small budgets and big goals, fighting the Sisyphean task of implanting a bike culture in the congested, choking car-centric cities of Latin America and beyond.

Los Mirlos playing “Bicicleta” at the opening night of the World Bike Forum

As has become my custom in the past few years, I give a “Charla Magistral,” kind of main speech—this time it was the last event of the FMB on Sunday night—and I do it in Spanish. When I watched the video later I had to cringe over my horrible delivery and bad pronunciation, but overall my Spanish is much better than any time previously, and I was able to converse pretty freely with everyone. Some people’s accents are nearly impossible to understand, but I was happily surprised at how many long conversations I was able to have in Spanish after so many years of not being able to. I even did some interviews in Spanish without any help or preparation—I think the interviewers were kind and spoke very clearly and slowly so I could follow their questions, and then I blurted my mangled spanglish and it seemed to turn out OK.

It was great to reconnect with a lot of the “regulars” at the FMB. We’ve become good friends over the years, from my very gracious host in Lima, Octavio, to friends from Mexico, Colombia, Chile, and Brazil, Panama, and even the Dominican Republic. This year we all made friends with two guys who traveled all the way from Kathmandu, Nepal, and by happy surprise, they were awarded the FMB9 in 2020! So maybe we’ll all find enough money to make our way to Nepal in 2020… that’s a dream.

Renata Falzoni, legendary Brazilian bike activist for decades, well known for her ESPN era, and now has her own bike channel

Edgar, Claudia, and Bruno, good friends from Arequipa…. I had a great time with Bruno and Claudia in past Forums and the great pleasure to meet Edgar this time.

Ceviche! Peru’s is the best!… we ate very well…

Lima is not a bike-friendly city, and part of the reason for the Peruvians to hold the FMB was to create momentum for more bicycling in Lima and Peru more generally. There are plenty of small groups and some genuine activist commitment, but clearly the city has not embraced the agenda very strongly. There are some bike lanes here and there, mostly in the wealthier parts of town, but they are not heavily used. As soon as you leave a formal bike lane you are thrust into curb-to-curb aggressive traffic. The only saving grace is that it is often gridlocked, so if you’re clever about weaving through blocked cars, you can make your way across the city much faster than someone in an automobile. I have ridden for decades in horrible urban conditions so I wasn’t particularly dismayed at riding in Lima, but it had been a while since I was on streets that really left no room at all to squeeze along the right-hand side. I improvised with some sidewalk jumping and other evasive techniques and fortunately had no problems.

Along the shore cliffs, high above the Pacific, you can find a very nice multi-use path with bike area… in the wealthy part of town.

On Avenida Salvaterry there was a very nice bikeway down the middle, but not heavily used.

A smattering of in-town bike lanes, but not a lot of cyclists, and no connectivity to actually get you across the city.

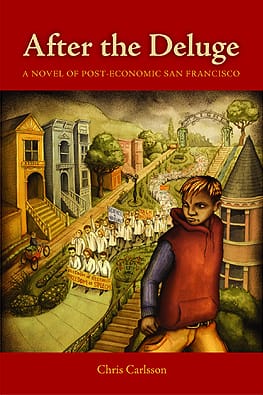

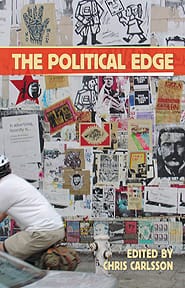

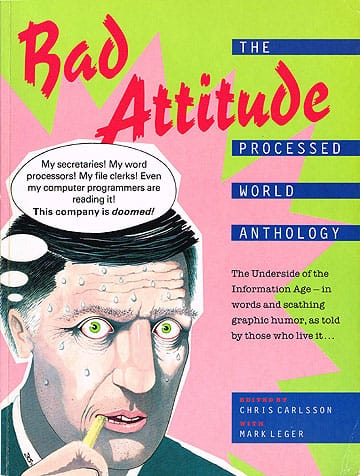

The Talk I gave is derived from a much longer article I wrote on the idea of a “Bicycling Commons” for a forthcoming book in 2019. (The article goes into some detail about the role of mainstream cycling advocacy falling for neoliberal agendas and helping to derail the Commons aspects that had emerged in the 1990s around the bicycling culture.) In the short excerpt I gave in Lima, I had to explain a bit about the idea of a Commons, since it’s not used in the same way in Spanish, and for the most part, it’s a difficult concept to translate. Interestingly, the next FMB in Quito took the Andean concept of Minga as a theme—it’s a concept that refers to shared collective, cooperative work (in U.S. English we’d probably use as an example the obsolete idea of a barn raising), but they’ve cleverly turned it into a verb and we are all thinking creatively now about how to “mingar” everything!

Here is the English version, with a few awkward parts thanks to having translated it back and forth several times now. I tried to smooth them over, and thus it’s a little different than the Spanish version I gave out loud. The Spanish version is posted as a separate entry.

The Bicycling Commons

A Bicycling Commons is a curious concept. Usually when we speak of ‘the commons,’ we refer to land or resources (a water supply for example) used and cared for in common by a group of people. Commons thrive on the basis of the culture that sustains them. Rather than referring to a specific land or resource, a Bicycling Commons refers to a shared state of mind and a shared set of experiences. What animates the notion of a Bicycling Commons is that so many people who have chosen to bicycle in cities feel they are a part of it.

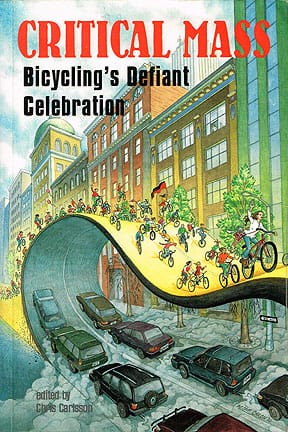

Let me explain this concept through the history and experience of the Critical Mass.

In the dense Lima fog we waited for the rest of the riders to catch up.

A long Critical Mass on the last night of the Forum took us through the historic center.

Like the original commons that were open to all, Critical Mass was open for anyone to join. Almost by accident, the space opened by cyclists attracted thousands of new participants who, upon entering this unexpected social event, directly experienced the new Bicycling Commons. When hundreds and thousands of cyclists took to the streets for a pleasant and festive use of public space, many of the expectations and rules of modern capitalist society were challenged, at least implicitly. It was a free exchange between free people. The experience altered the meaning of life in the city immediately and, more importantly, changed the collective imaginations in ways that we’ve only begun to understand.

Cruising through Lima.

Another pause, another moment to say hello and celebrate our defiance!

Critical Mass riders found themselves practitioners of a new type of social conflict. By pedaling in urban centers, Critical Massers repudiate the social and economic models controlled by multinational capital and the ways of life that had been imposed without any form of democratic consent. This massive seizure of streets by a crowd of “leaderless” cyclists was precisely the kind of logic of self-management and networking that has been transforming our economic lives and threatening the structure of government, business and even military strategies.

Saying hello to my Colombian friends on the first day.

With Laurita and Veronica from Quito… hoping Laura becomes a bicycling historian in Quito!

By 1994 there were many Critical Masses around the world, but even more interesting was that many people began to ride bicycles every day. Cyclists opened DIY bicycle workshops, started bike ballet groups, bicycle circuses, midnight rides, and launched pedicab businesses. Others produced an endless stream of magazines, hats, stickers, posters, buttons and a remarkable profusion of creative expressions related to the bicycle. Today, hundreds of thousands of people ride bicycles every day instead of driving cars. Since about 1990, the world has begun the shift from clinging to the cars of the twentieth century to a multimodal approach to urban transport that emphasizes cycling and walking, complemented by public transport. Undoubtedly, there are still strong political and economic forces that resist this transition, especially given the central role of the automobile and petroleum industries in most national economies. But, literally, millions of citizens around the world are “voting” directly in favor of change by riding bicycles. This is a surprising result of a slow collective decision to change life that started in a small place, then spread to other places and finally led millions of people in hundreds of cities around the world to change their daily behavior.

On the streets of Lima.

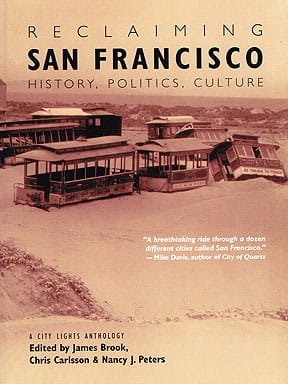

In San Francisco where I live, cycling has also grown since the early 1990s. We have had a huge increase in daily bicycle trips during this period, but as cycling has normalized, what was once a dynamic culture of cycling has largely disintegrated. Critical Mass still rolls every month, but it has been a long time since I thought it magical or inspiring. In general, it is a very predictable and quite boring trip these days, without much conversation or discussion.

Warm but foggy, our outdoor gathering in Estadio Bonilla was mostly very comfortable.

Annoyingly, the local police had a precinct office in the stadium and were patrolling us like crazy, searching for banned alcohol and other substances…. There should have been a negotiated truce for the duration of the Forum!

Not a huge attendance, but those of us who were there had very interesting conversations and a great time.

We had three “salas” outdoors on the field.

Like all successful social mobilizations, Critical Mass altered the direction of public policies. After years of the monthly taking of the streets by hundreds and then thousands of cyclists, city leaders began to build bicycle lanes, install bike racks and adopt a public bicycle program. To the extent that some of the most urgent demands and expectations of Critical Mass riders were met by the state and its officials, the Bicycling Commons began to lose its opposition strength. As the government slowly began to make changes in the infrastructure of modern life, the Bicycling Commons was unable (and unwilling) to maintain itself as a partner of the state bureaucrats. The planners implemented changes and ignored any ability of the culture to govern itself and make its own decisions outside state structures. The cyclists accepted the bicycle infrastructure that was emerging with varying degrees of enthusiasm, but those who had a radical vision of the much deeper changes that emerged from the Bicycling Commons found themselves isolated. Some streets and sidewalks have changed, but the society that originally imposed private cars and dependence on oil has not changed at all, and the predominance of automobiles and oil has not eroded much either.

Arriving in Lima from the plane…. very dry!

Approaching San Francisco on my return… so clear!

****

Along with the resurgence of the urban cycling movement, a deeper transformation has been underway for several decades in our cities. The urban centers that were abandoned during the apex of automobiles and suburbanization have once again become the most desirable places for the middle class. The new generation of young urban professionals wants more public space, better public transport and more spaces for cycling and walking. But these desires have been co-opted by the capitalist market. The so-called “sharing economy” companies such as Uber, Lyft and AirBnB are cloaked in the rhetoric of the Commons, but they have co-opted these desires to design a brutal market of micro-rentals, subjecting each unoccupied block of time in a car or home to possible sale. Worse yet, these changes have taken place mainly in urban neighborhoods that had served as safe havens for the poor and the working middle class.

In San Francisco, I live in the Mission neighborhood. The Mission has been a working-class neighborhood for almost a century and of Latin American immigrants for half a century, but in the last decade it has succumbed to a wave of gentrification fueled by the wealth of Silicon Valley. The engineers of this change have been real estate speculators who have carefully marketed the neighborhood precisely because of its qualities of authenticity, accessibility and vitality, which newcomers are looking for. The waves of artists, queers, punks and others that gave flavor to the neighborhood, along with the original ‘Latino’ working class, are being replaced by uninteresting and confused but well-paid employees from the technological, medical and financial industries.

Parklet in front of worker-owned collective bakery Arizmendi, while across Valencia two huge luxury Tech buses roll down the street, bringing/taking employees to or from their jobs in Silicon Valley.

Ironically, now that the culture of Critical Mass has unraveled along with the sense of the Bicycling Commons, San Francisco has become the most traffic-congested city in the US, due to the insidious gentrification and the arrival of the Ubers, Lyfts. and other rental car services. These new taxi services transfer the burden of providing accessible public transportation to private drivers exploited and indebted for their cars. In San Francisco they have added ten to twenty thousand cars to the streets of the city. Above all, it is precisely these new taxi services that constantly invade the bicycle lanes that have cost us so much work to establish.

Valencia Street in SF, where the first bike lanes of the recent era were installed, only to be filled now by Uber and Lyft drivers who obliviously cruise along staring at their phones.

In the Mission, there is an organization of working-class Latinos called PODER, which is dedicated to fighting for economic and environmental rights. It is not surprising then that it is here that a group of young people on bicycles called Bicis del Pueblo has been formed. They are the best and maybe the last example of an independent and politicized bicycle culture in San Francisco. The group organizes monthly bicycle building workshops, organized group tours and more, to serve their neighbors and families in South San Francisco. Bicis del Pueblo’s agenda is not only ecological or for a better urban design, but it is also based on the desire to expand social justice.

By the way, they sent greetings via video:

In Los Angeles there is another example: the Ovarian Psycos are a band of female cyclists who are pushing the limits of racial and gender exclusion in the bicycle scene. For them, bicycles continue to provide a means for social groups to assert their independence, their opposition to the dominant patriarchal culture and to enact a partial agenda of urban transformation.

Silvia López, one of my many new friends from this FMB, gave a spirited presentation based on her experience in Valencia, Spain, where she has a bikeshop in what was once a depressed neighborhood but has begun now to gentrify.

I give you these two examples from my Californian lands, because we must be attentive to the processes that unravel our most precious resource: the Bicycling Commons, which at least in its beginnings, seeks to expand and not restrict access to a better quality of life for all. In advancing our cycling agendas we must oppose the interests of the real estate industries, politicians and businessmen who prefer to promote cycling as simply transport without political ends.

Riding across Lima in heavy traffic with a group from the university to the stadium on the first day.

Social solidarity has been torn apart in societies everywhere by the terrible consequences of neoliberal capitalism and austerity, and our apparent impotence in the face of global climate change. But a new kind of solidarity—implicit in the Bicycling Commons—has helped many find a remarkably joyful connection with their sister and brother cyclists. The funny thing is that this “cycling culture solidarity” has been largely a phenomenon of middle and upper-middle class. The new culture of the bicycle has taken root among the parts of the population that perhaps were more separated from the kind of daily solidarity that has always been the hallmark of the poorest communities. People who have suffered poverty or are too far away from modernized cities are those whose human solidarity has always been more resilient. They have known how to build social bonds and organic communities outside the logic of an economic system that reduces all interaction to trade and transactions. We who have participated in the Bicycling Commons manifested in Critical Mass and its related spaces have much to learn from the public life created by impoverished and resilient communities. If there is a future for the Bicycling Commons, it seems that it will be based on expanding inclusion. At the very least, it is necessary to broaden the recognition of the Bicycling Commons that exists in other communities, which have not been attracted or feel excluded by the middle class culture that typifies the urban bicycle scene. For example, we can look towards the so-called “Pueblos Bicicleteros” (a term used derogatorily against “old-fashioned” small towns in Mexico) to imagine a better future where modernization has not destroyed everything. Where healthy ecosystems survive along with traditional ways of living, cultural diversity, and memory.

The Bicycling Commons exploded in the public consciousness 25 years ago, mainly through the contagious pleasure that the phenomenon of Critical Mass helped to spread around the world, and the opening of the forgotten public space of our shared streets. But the Bicycling Commons as an animating force is reduced when the bicycle is simply a practical device, simply a way of moving or an object of commercialization or regulation. Cycling must be part of a more expansive agenda that challenges:

1. the logic of incessant growth,

2. a world based on the commodification of humans and their creativity,

3. the reduction of nature to “resources” subject to bureaucratic regulations, and

4. discrimination based on race, age, gender, and wealth, among other things.

When that happens, then a Bicycling Commons can thrive.

The Bicycling Commons opens a space where we can seriously talk of producing a different way of moving and therefore a different way of living. A deeper agenda lurks within our spinning wheels, but it can disappear quite easily if we stick to the narrow agenda of those who can not distinguish the forest from the trees, who cannot see that riding a bicycle is just a door to a much bigger transformation of how we forge life together.

Thanks for your attention.

Leave a Reply