This is a Talk I gave at The Battery, a ridiculously chi-chi private club at the edge of downtown San Francisco. The event, “Gentrification and the Changing Nature of San Francisco,” was organized by Broke-Ass Stuart, who somehow came to be one of their current artists-in-residence. I have to say, I felt pretty uncomfortable there, and I’m sure a number of my co-presenters were in the same boat, especially Michelle Tea and Maryam Rostami… and though the event was promoted as a way to generate dialogue between us ostensibly “authentic” San Francisco writers and artists facing displacement and eviction, and the nouveau riche of The Battery (private membership = $2,500/yr!) who might be partly responsible for our precarious situations, by the time I got up as the penultimate speaker, about a third of the attendees had already departed, and no one had much energy left. After the unbearably self-serving, pretentious, contradictory, and laughably arrogant presentation at the end by Roberta Segal, Stuart thanked everyone for coming and no dialogue was invited. So much for that!

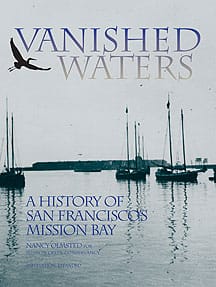

On my first day back from vacation yesterday morning I went up Bernal Heights in bright sun to find that the bay was engulfed in low-lying fog. So beautiful! Here are some ships at anchor, emerging ghostly from the fog with Mt. Diablo in the far distance behind the Oakland hills.

Gentrification and Liberalism, San Francisco and Beyond

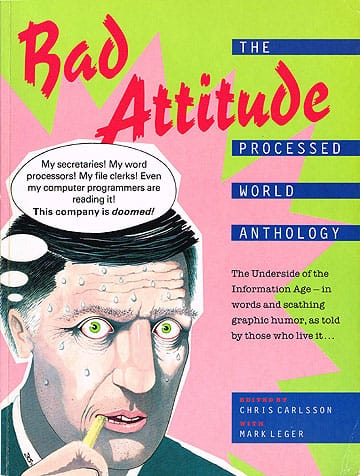

Thanks for inviting me to participate. I’m a local historian and a long-time writer about the stupidity of modern work and the field of economics, so for starters let’s just say that gentrification cannot be addressed in isolation from social amnesia or work. I think gentrification is a concept that hides as much as it purports to reveal. The word sometimes functions as a marker even while it can allow us to leave out history or broader questions of how we organize the production and reproduction of life in all its complexity.

The physical spot we’re in here at The Battery has gone through some mighty transformations in the relatively recent past. We are here on a spot that used to be part of San Francisco bay. Not so very long ago, less than 200 years, a couple of blocks west of where we are was a beach with a creek burbling in about where the Transmerica Pyramid is now… in 1837 the first house was built by William Richardson at apx. today’s Clay and Grant (up in Chinatown) and years later his son told a story about sitting on the porch gazing down sandy slopes at the mudflats revealed by the low tide. There he saw dozens of huge fish, probably sturgeon and salmon, beached in the mud by the tide, being fought over by a coyote, a wolf, and a grizzly bear.

The old Barbary Coast grew up here along Pacific Avenue, originally on piers and platforms over the open bay. It was home to vice and crime of all sorts, perhaps the most dramatic being “shanghaiing”—the business of providing sailors to ships, by hook or by crook. An 1897 U.S. Supreme Court decision excluded civilian sailors from the 13th amendment’s protection against involuntary servitude, arguing that sailors were deficient in that full and intelligent responsibility for their acts that is accredited to ordinary adults, and therefore must be protected from themselves in the same sense in which minors and wards are entitled to the protection of their parents and guardians!Decades of organizing sailors into unions finally led to the banning of “shanghaiing” in 1906.

Fifty years after that, this area was a teeming center of the produce district. Most people were speaking variations of Italian and the abundant produce of California’s agricultural industries flowed from inland empire to the City’s waterfront finger piers, and from there into the wholesale markets, canneries, and other facilities that made this the heart of Italian North Beach. In the 1950s a double-decker freeway was built along the waterfront ending—temporarily, thought the highway planners—at Broadway, with on and off-ramps just a block from here. The relatively new-at-the-time Redevelopment Agency chose this part of town for its first major project—the removal of the Wholesale Produce Market and the expansion of downtown east and northward. This modernization process also led to the destruction of the old Montgomery Block, home to dozens of San Francisco’s bohemian artists and writers for many decades, and its eventual replacement by the Pyramid.

Concerted efforts by local citizens led to rezoning of the Jackson Square historic district before it was engulfed by new highrises. Another dynamic political movement arose to oppose the crisscrossing of San Francisco by elevated freeways, ultimately stopping over a dozen plans and eventually, with a helpful earthquake in 1989, leading to the removal of the Embarcadero Freeway and the flourishing of a tourism-based economy along the waterfront. That could only make sense because another huge social movement had finally changed our relationship to the San Francisco Bay. For a century it was a given that filling the bay was a good thing and finally in the early 1960s people organized to stop it. They largely succeeded with the creation of the Bay Conservation and Development Commission and subsequent environmental regulationssuch as the Clean Water Act. Today, saving the bay, along with the freeway revolt, are foundations for the environmental and urbanist movements that are still battling to make this a good place to live.

I arrived in San Francisco in 1978 at the age of 20 and moved into an apartment on Cole near Haight when Haight Street was 50% boarded up. At the time it was slummy, trashed, full of alcoholics and drug addicts, depending on its exaggerated reputation derived from the hippie era. Within a couple of years, it was gentrifying, and by the time I moved to the Mission in 1987 people had been complaining for years about how the Haight was being taken over by yuppies.

Gentrification has been going on for several decades at least, but we tend to notice it episodically when the effects are most extreme, when neighborhoods and communities are at their most threatened. The word itself probably obscures as much as it reveals at this point.

What we’re experiencing these days is called in many parts of the world “neoliberalism.” Neo of course means new, so what is this new liberalism and how is it different from the Old Liberalism that preceded it? I think this distinction is an important one for understanding what is different about how gentrification is affecting us now, compared to how it was when I saw it beginning in the late 1970s in the Haight.

Precisely at that time, during the presidency of Jimmy Carter, and in the wake of Nixon’s southern strategy that coaxed millions of white racists into the Republican party, the Old Liberal coalition that had come together under Franklin Roosevelt in the New Deal was falling apart. Old liberalism had strong proponents in San Francisco, mostly Irish Catholics from the Mission District who dominated City and state politics during the middle of the 20th century. Old liberalism had a purpose, forged in the Depression of the 1930s. It was strongly opposed to laissez-faire economics, and understood that Capital could not be given a free hand without serious damage to the fabric of life. Regulation and government economic intervention were necessary to achieve fairness and prosperity for the majority of the population. These liberals were also believers in the American way of life, including private property and the importance of so-called free enterprise. They saw themselves as the only hope to save capitalism when it was threatened by the godless communists, who were not only atheistic but totalitarian. During WWII liberals and communists worked together to defeat fascism and for a brief moment at the end of the war it seemed that a kind of Scandinavian social democracy might emerge in the U.S. too, with guarantees to housing, health care, decent jobs, public education, social security, and more.

But the Cold War and the possibility of nuclear war overshadowed everything. The largest strike wave in U.S. history in 1946 led to the passing of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 by a Republican congress determined to curb the power of the working class to win strikes and expand its power. Moreover, though they joined the consensus on the liberal expansion of the state, the conservative politicians of that time made sure the vast majority of that expansion would be oriented towards empire and the military. In fact, the interstate highway program was sold by Republican President Eisenhower, the former WWII general, in part for its importance to military defense. Old liberals closed ranks with conservatives against the communists during the Cold War, often becoming aggressive hawks to prove their patriotism. During this era, there were liberals and conservatives in both Democratic and Republican parties, a reality that didn’t really begin to change until the breakdown of Old Liberalism in the 1970s.

Meanwhile the U.S. economy enjoyed its unchallenged global supremacy from WWII to the late 1960s when competition re-emerged from the war’s losers, the Japanese and Germans. During that boom period under Old Liberalism, the American “middle class” as we think of it now was invented, but it wasn’t really anything but a better paid working class. Weekends, vacations, employer-based health insurance, higher wages, 40-hour weeks, all became routine during this period. But the price-tags of the Vietnam War and the Great Society programs proved too much by the end of the 1960s. Nixon took the dollar off the gold standard, and after the 1973 Israeli-Arab war, OPEC imposed an oil boycott which doubled the price of energy in a year. By the mid-1970s the world built by Old Liberalism based on cheap oil, U.S. military and economic power, a well-paid but politically conservative working class that was convinced that it had become “middle class” through profligate consumption, was falling apart.

Deregulation, privatization, and ruthless attacks on public spending began under Jimmy Carter and were greatly accelerated under Reagan in the 1980s. Old ways of living were disrupted, vast swaths of the industrial heartland were turned into a Rust Belt, and people moved by the millions to the south and west. Consumerism was radically expanded by the rise of malls in the suburbs and the creation of global shipping based on the container, which combined with rock-bottom wages and zero environmental controls in large parts of the Third World to make clothing, electronics, and all sorts of goods cheaper than ever. Suburbanization reached its zenith in the 1980s fueled by a deregulated Savings & Loan industry engorged on junk bonds. Oil prices had fallen, food surpluses based on fossil-fueled, hyper-productive corn and wheat kept prices low, automobilization was the sole answer to transportation needs, and the military budget expanded repeatedly as the Keynesian motor of U.S. capitalism. Massive military expenditures gave rise to the internet and modern computing as well.

When the Hunters’ Point Shipyards were active this massive crane (floating in the fog in this photo) was used to lift thousands of tons to equip naval ships.

It was during this radical reorganization of the world that neoliberalism came into its own. The neoliberal “Washington Consensus” imposed by the World Bank and IMF on country after country led to the gutting of the public sector and the privatization of water, schools, roads, and more. New telecommunications capacities facilitated the management of far-flung networks of mining, production, and distribution from the global cities at the heart of the world economy: New York, London, Paris, Zurich, and even San Francisco. Currencies rose and fell, stock markets expanded and prices rose only to crash in the newly deregulated environment. Capital moved heavily into real estate and housing as hedges against uncertainty in financial markets.

This New Liberalism was and is dedicated to the untrammeled power of capital. No longer fearful of an insurgent working class or a global communist “conspiracy,” liberalism returned to its 19th century roots, promoting individualism, self-reliance, private property rights, and a reduced public sector. Publicly financed health care for all, strengthened environmental protections, public investment in economic development and infrastructure, all came to be seen as tired tropes of the failed Old Liberalism. The New Liberalism advocated private investment and markets as the mechanism that would solve any and all problems of economic development or distribution.

So we find ourselves in the heart of one of the cities that have taken this logic to an extreme. Market-rate housing has benefited investors and the super-rich exclusively. Housing policies here have largely followed the national pattern, gutting public subsidies in favor of private solutions. Thousands of people rendered homeless by three decades of these public policies favoring private solutions are portrayed as weak, lazy, morally bankrupt, and deserving of their fate. The ongoing squeeze on the working class who do the teaching, hospital work, firefighting, hotel keeping, restaurant cooking, etc. is pushing them out of the city and into far-flung suburbs. Artists, writers, and cultural producers of many types find they cannot enter the flow of life in San Francisco unless they are already wealthy, or ready to sacrifice their art to work in well-paid tech companies. Life in San Francisco is succumbing to a creeping and creepy monoculture, but it could be so different.

First of all, a city worth its salt needs to take its own memories seriously. Gentrification’s role in churning the population contributes mightily to a culture that can’t remember its own past. San Francisco makes no sense without knowing and honoring the social movements that fought for it. From Casper Weinberger’s curious role in preserving waterfront views and height limits, to the movements to save the bay, stop the freeways, and halt nuclear power, to our resilient anti-war population that has taken to the streets against every conflict the U.S. has been in since Vietnam, to the still-unfolding movements that started with Occupy and have re-emerged as efforts to combat racist police violence, San Francisco is home to energies that live on in the present but are deeply rooted in a multi-generational lived experience.

Amidst the hand-wringing over gentrification, we rarely discuss the underpinning to this whole system: the work we do. Together we make the world we live in. Working together we could be producing a beautiful life for everyone, not just here in San Francisco, but for everyone on the planet. This would require reducing and eliminating a great deal of the stupid work done now, and an intelligent reorganization of how we do things. Technologies have roles to play, but the missing link is a social process of decision-making. How do we want to live? What should be the basic minimum for everyone? How can we get there, what is the work we need to do to produce such an achievable utopia? How do we evaluate the ecological consequences of that effort and learn to work with natural systems instead of against them?

We rarely ask such basic questions, partly because there is no venue for it. There is no mechanism in our pseudo-democracy to decide together what to do, how to do it, at what pace and with what consequences, socially and ecologically. Instead, we rely on weird fetishisms about the “health of the market” and wait for those with wealth to decide what to invest in, hoping that maybe we can through some minor tax or public policy incentive divert some social wealth into actual social needs. The housing question is a central one, but the gentrification discussion tends to avoid the elephant in the room: private property. A social system based on private property as the supreme right over all else, will unavoidably produce great inequality and intolerable injustice, not just in housing, but across the board.

It’s time to recognize that life is a grand cooperative venture and the more radically we democratize it in all aspects, the better we’ll be able to address the crises we face. Whether it’s climate chaos, gentrification, brutal police and military acting with impunity in our name at home and abroad, ecological devastation, or whatever, a major rethinking and reorganization of how we produce and share life is at the heart of the solution.

Thank you.

Nowtopian – you are one my favorite writers. Great sensibility, ideology and appreciation for history and landscape and all the best of urbanism and culture and visual beauty.

Thanks for the history of the Barbary Coast and I always knew what the phrase to shanghai meant, but I had no idea that the Supreme Court actually ruled that is was legal!

Yes, we’re also looking for an end to that stupid work and towards meaningful work – and the joy of just living without all the BS

That’s why I love your work – you pose the essential and eternal questions!

Hi… People have gotten upset somewhere on facebook regarding Chris’ intro to this blog, in which he calls out Roberta Seagal’s presentation. I was there at The Battery and I had to walk out of Roberta’s talk because I found it insulting to myself and the other artists in the room, while madly pandering to the wealth in the room to finance her “solution”. I suggest that just like Chris, Roberta publish her Battery reading online so those not present can read for themselves her “solution” to scarce housing for artists.

Among points she made: (1) Nothing art worthy has taken place in SF since Burningman, (2) Rich people need to finance her idea to make existing housing in SF available to artists, (3) the Solution requires handpicking the “best” artists to be allowed to live in these exclusive artist colonies in SF, and (4) All of the financing and building acquisition should be funneled through her non-profit organization … I’ll leave it at those four points which are part of her solution… An exclusive and narrow solution, at that, because it reinforces exclusivity and scarcity.

Roberta advocates for a solution that acknowledges private property and the market as the reason why housing resources are scarce, but avoids any critique of this premise. As far as artists are concerned, it seems she would like to see a return to fuedalism, where only artists chosen by the landed gentry get support. In this manner, Roberta’s solution is one with the problem. I too expected a conversation to take place after the talk and would have gladly said this and more publicly. I walked back into the room once I heard the clapping…

Several of the artists invited to the Battery are know for non-normative and even politically radical points of view. Why you should be surprised that there is a critique of Roberta’s solution is baffling to me… That’s what we do. Missing at the talk were local artists Latino, Black or Asian or other minority voices born and raised in SF. THis is not to say that they had to be invited, but that there was a homogeneity to the vastly white artists presenters that needs to be acknowledged. Michelle T described in her reading how she had moved into the Valencia corridor decades back to be part of the cohort that changed the demographics and landscape of the Mission. That points to self-critique. Artists can also be part of the problem.

I am a writer and artist, a Mexican national, who in the last year spent time working on a project with legendary Chicana artist Yolanda Lopez to highlight her no-fault eviction from her Mission home of 35 years. I’ve also collected narratives of other lifelong Mission locals being pushed out of the City. I’m interested in the artists and writers who are politically engaged with the issues of inequality and injustice of their time. I could not disagree more with a solution that avoids talking about the inequalities of wealth fueling injustice in the City. It seemed shameful to me that in the context of inviting critical thinkers to the Battery, the closing talk was about abandoning any such thought, and asking for a hand out. I thought we were there to dialogue and challenge each other, that is, to engage the gap between the Battery club members and the artists, not encourage it.

In any case, Roberta can propose whatever she likes, but given the public nature of her comments at The Battery, a follow-up discussion was sorely missed to air out divergent points of view from artists and audience. Too bad, I would have liked to experienced a public discussion of these issues at the Battery…

Hi Chris – wow I love what you’ve written. I love your characterization of “the stupidity of modern work”. That’s how I’ve always seen it…..

I can just see the gentry in attendance squirming in their seats. Your broad view probably isn’t something they’ve considered. Did any of the club members approach you afterward?

Your photos are beautiful, too. It’s obvious how palpably you love this city. With the current wave of cultural annihilation going, I have to wonder how many of the people coming here really get the essence of this place – it’s eclectic nature, it’s geography, it’s vividness, it’s exquisite surreality. Else why would it be becoming something else entirely?