Went to see the just-released film “Why We Fight” yesterday. It’s a very well-made, sound bite-style documentary. It begins auspiciously, with Eisenhower’s 1961 farewell speech in which he warns against allowing the military-industrial complex (M-I-C) to gain unchecked power. Then Gore Vidal appears to announce that we live in the United States of Amnesia. So far, so good.

But as we were leaving the theater 90 minutes later, Hugh told me he didn’t like the film. So we spent the next hour dissecting why. Mainly, the film frames the title’s claim in terms of a bipartisan, industry-driven expansion of the military since WWII. At a certain point every president since Truman flashes by along with a map showing the three dozen or so military interventions and invasions by the U.S. around the world since 1950. While much better than no reference to any of these at all, none are given more than a cursory mention except for the overthrow of Mossadegh in Iran in 1953 (and the ensuing installation of the Shah, which eventually leads to the 1979 revolution and the Iranian theocracy).

The film explains that in 1953 the British were angry after Mossadegh tried to negotiate a better deal for Iran and when the British refused, the Iranian parliament voted to nationalize the oil industry. The British turned to Eisenhower who obligingly labeled Mossadegh a communist (he wasn’t) and green-lighted the CIA-organized coup. This short schematic, sandwiched within a larger narrative, doesn’t really do justice to the complexity of history, to say the least. But this movie is not about a detailed analysis of any given use of the U.S. military, but rather to look at the half century process in which the M-I-C has taken over the government and made itself practically invisible in its ubiquity.

The film is a good antidote to the current last gasp of liberalism, which frames the Cheney-Bush regime as a rogue departure from a democratic norm, a fantasy United States that is basically “good” but has been taken over by a cabal of evildoers. (In this common narrative, plastered all over the blogosphere, from DailyKOS to MYDD to FireDogLake, the Democrats are still the good guys who just have to right the ship of state–this ahistorical, amnesiac frame dovetails perfectly with the regime’s own Manichean worldview.)

Unfortunately, “Why We Fight” makes the same mistake of history that it is is critiquing. The origin of the United States’ culture is based on Indian eviction and genocide, and African slavery. The M-I-C and the projection of U.S. military power dates to at least the late 19th century. The annexation of Hawaii and the Philippines in 1898 (followed by a 15-year war in the archipelago of incredible brutality) are the real beginnings of what Ike and this film frame as a post-WWII phenomenon.

It is perhaps beyond the scope of a documentary film, but a proper historic framing of the M-I-C would also trace the shifts in the world economy since the late 19th century, and relate the military empire of the U.S. to its role as financial coordinator and ultimate beneficiary of the world economy. The IMF and World Bank, e.g., don’t even get mentioned in the film.

The filmmaker allows the loony right to have its say quite a bit (can anyone doubt the palpable insanity of Donald Rumsfeld?). Richard Perle, the ultimate smug bastard, goads liberals directly by asserting that there will be no turning back to a pre-Cheney/Bush foreign policy. These guys have not only altered the geopolitical landscape. Crucially they’ve altered the polity in ways we can’t fully know for years to come.

That leads conveniently to another theme that popped up on Commie Curmudgeon–solidarity. Solidarity is a concept that depends on continuity and history. Its relative disappearance in U.S. culture is closely connected to Perle’s assertion, and to the ongoing erasure of history and truth as meaningful categories in our daily lives. In an In These Times article by Christopher Hayes, solidarity is distinguished from the more common charity that progressivism has degenerated into:

Right now, our politics are atomized and transactional: we send checks, we sign petitions, we forward articles. We buy sweat-free clothes, recycle and look for vocations that don’t collude too egregiously with evil. But we’ve unconsciously circumscribed the boundaries of political action. What is MoveOn’s equivalent of a strike? As union membership and urban ethnic machines decline and the “netroots,” overwhelmingly white and affluent, comes to represent the progressive movement, the left is in danger of becoming, as Thomas Frank wrote in Le Monde Diplomatique in February 2004, “a charity operation.” That is, “people in sympathy with the downtrodden, not the downtrodden themselves.”

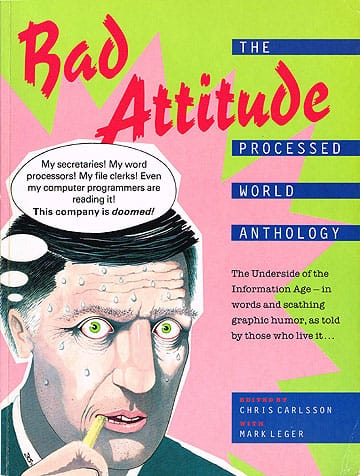

I’ve been railing about this since the early 1980s when we started Processed World as a forum to address our own situations. Politics, the kind of politics that really animates change, cannot arise out of wanting to do good on someone else’s behalf. First and foremost we have to recognize how our own lives are degraded and stunted by living in capitalist (racist, misogynist, homophobic) society. Our dissatisfaction and rage with our own lives has to be the starting point. From that kind of powerful subjective engagement with the potential of our own lives being made radically better we can meet others in a wide range of conditions and states of mind with authentic solidarity; a solidarity based on mutual respect and a mutual understanding that our lives can only be reclaimed and redirected under own control in collaboration.

Kudos to Commie Curmudgeon, too, for rebuking leftist depression over the decline of unions. Paralleling the ahistorical fantasies liberals have about Democrats, people committed to radical social change are too often delusional when they think trade unions are on their team. The vital distinction between self-organization (in workplaces or neighborhoods or otherwise) and the institutions which have developed in capitalism to stablize an exploitative daily life is too often lost or never properly understood. Of course we all need to figure out the new forms of politics and self-defense and utopian upheaval that can really overturn this barbaric world. But too many leftists in the U.S. are unimaginatively stuck in a moribund loyalty to forms and institutions that have been properly abandoned in practice by most people.

My friends at Retort who published Afflicted Powers have been getting due attention for their important book. In the current New Left Review Julian Stallabrass critically engages with their effort and reminded me of why Afflicted Powers is so good. In their analysis of the spectacle, Retort helps explain why solidarity is so attenuated, since the function of the spectacle is to atomize and fragment social life.

Stallabrass: “The nightmare of the spectacle, write Retort, is that of living in an eternal present, sundered from history and tradition, while prey to an unknown future a life of fundamental meaninglessness governed by the contingencies of the market.”

Stallabrass argues that Retort has overstated its case (like the Situationist critique in general, perhaps).

“Retort claim that commodity society and spectacle are ‘endlessly parastic on the values of a vanished sociality.’ But if that is so, the endlessness of the process implies that sociality is being rebuilt at the same time as it is being colonized and simulated.”

This is exactly correct. The ability of capitalism and spectacle to persist at all depends on a perpetual renewal of human life beneath it, a life that is fundamentally cooperative and social (and deeply antagonistic to the logic of capital). The project of capitalism, of which the spectacle is a crucial tool, is to colonize that everyday life of cooperation and break it apart and reduce it to commodities for sale. Insofar as we cannot clearly see how fundamental, creative and powerful our reproduction of everyday life is, and our own minds are colonized by the endless repetition of spectacular blather, the system continues to function, and even to extend its reach into more and more corners of our lives and the globe. We feel helpless and alone, when together we are all-powerful and fully capable of making life as we would like it to be.

Looping back to “Why We Fight”‘s failure to adequately frame the history it is portraying, Retort claims that neoliberalism (even or especially in its neo-conservative form) mutates into continual outright warfare in pursuit of primitive accumulation. Afflicted Powers is so good because of how well it unravels the longer view of U.S. strategic power, military adventures, and the role of spectacular images in this history. Like Arrighi and Wallerstein, their analysis points to the likelihood that we are entering the terminal crisis of U.S. hegemony. The M-I-C’s hubris, so well shown in “Why We Fight”, is fundamentally a delusional and ahistoric worldview. The despair or hysteria of liberals is not adequate to the times. A deep reconceptualization of radical politics, an elaboration of a vision of how much better life could be, is our historic responsibility now. Anything less is unrealistic.

Thanks for this entry Chris. I was grousing just before reading this over the new

Those BBC docs are by Adam Curtis, and why aren’t they available at our local video rental places? gol’dangit!

A good review of the film, which was worth seeing, but still has many deficiencies. My objection was not that the time frame was too short, or even that this or that pet issue was not discussed. (Though the coup in Iran is one of my favorite bits of buried “public” secrets which more people should know about.)

My complaint is that in this film, and in documentaries generally, ideas are never fleshed out or developed in any systematic way. We skate from one brief flash of info to the next. Yes, I know that television news is much worse in this regard. So what? It’s still a debased form of communication in which the real issues are only barely hinted at. As an example, I would point out that you could ingest all the information in this 2 hour film by reading a short magazine article in 5 minutes.

A good counter example of a documentary done well is the Century of The Self, and also The Power of Nightmares, BBC docs by a guy whose name I’ve forgotten at the moment. These films take a novel approach to complex subjects, keep you engaged and leave you thinking on the subject long after the film ends. No such luck with this one. I guess my expectations are too high!

H.

One could argue that the M-I-C began in the USA even earlier than the late 19th century. Early in the US Civil War, the North and the South had major ordinance shortages (the CSA got most of their arms via looting dead Union soldiers and raiding ammo warehouses).

By the end of the Civil War, there were TOO MANY guns in the USA, thanks to European manufacturers like France, and the rise of modern industrialism in the Northern US. This was one reason why we headed into late 19th century “expansion”.

This bit of history, along with the well-known fact that the US Civil War modernized warfare as the world knew it, is an earilier example of our/humanity’s drive to make a better killing machine…and develop a more efficient M-I-C.

Also, I agree with Justin on his “armchair activism” angle. I keep saying it: the only way to really foster a new, improved vision is if those Middle Americans get hit by a major economic collapse. That could come from a major event larger than 9/11, or from China, the country that currently floats our economy.

Take away the comforts that the spectacle gives them, shake their basic needs, make them feel the reality of economic precarity, and you’ll have millions of open ears. For now, they’ll just keep watching the Olympics and going to church.

Hi Chris,

Regarding the movie: I haven’t seen it (it sounds like a good history lesson) but your friend didn’t like it because it seemed too short on the time frame — war and killing has been part of U.S. history since the beginning. But can’t you take this even further and say the same for all of recorded human history? Genghis Khan and the Mongols, Roman Empire, etc – every nation state has risen to power and influence from conquering people. Maybe this is all just part of being human. 😉

Regarding the rest against the current progressive agenda: Yes there are certainly a lot of problems with our current way of life in the U.S. And I agree it will take individuals finding deep conviction from rage and dissatisfaction to make changes. But your average American leads the best life that’s ever been possible in human history. They’re educated, don’t worry about where there next meal’s coming from, have leisure time, friends, family, good health and can buy frivolous things. I don’t think people who have this life, no matter how progressive their politics or thinking, are going to find the determination to make the changes that one philosophically knows are needed. Hence the armchair activism through moveon.org.