I am popping in to recommend a listen for the 99% Invisible podcast on the Orange Alternative (which helped bring down the Polish military dictatorship in the late 1980s and ultimately ushered in the post-Communist era), which was centered around Wrocław in southwestern Poland. It’s a lovely radio show, full of inspiring history, and usefully brings it into the present by telling us about the “Little Picketers”—small clay statues holding signs that are popping up all over Russia as a kind of small, everyday dissent against the Ukrainian war.

I am popping in to recommend a listen for the 99% Invisible podcast on the Orange Alternative (which helped bring down the Polish military dictatorship in the late 1980s and ultimately ushered in the post-Communist era), which was centered around Wrocław in southwestern Poland. It’s a lovely radio show, full of inspiring history, and usefully brings it into the present by telling us about the “Little Picketers”—small clay statues holding signs that are popping up all over Russia as a kind of small, everyday dissent against the Ukrainian war.

A few images of “Little Picketers” that The Nation published, at least a couple originated with The Moscow Times.

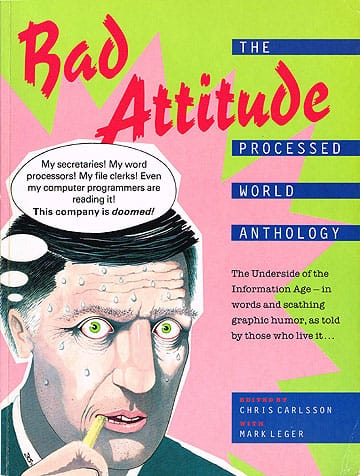

At the end of this post I’ll put the unfinished video of a journey through the last days of the East Bloc by the “Anti-Economy League of San Francisco”—we went to warn our political friends in East Germany, Poland, and (then-)Czechoslovakia about the coming disaster of “freedom.” That was our logo at upper left (taken from Oscar Bernal’s back cover of Processed World #8).

The Orange Alternative, well-presented in the 99% Invisible episode, was very inspiring to us when we learned about it. Using the symbol of a smurf, the movement grew by leaps and bounds and filled the streets in many places, especially Wrocław, using humor, ridicule, and festival to reduce the military dictatorship to the butt of a joke.  These days it’s hard to laugh in the face of the Russian onslaught on Ukraine, but we have to admit that meeting military might with the same is basically destroying the country. As Steven Cohen usefully analogized on the New Yorker Radio Hour, say you live in a big house with 10 rooms. A big bully comes barging in and takes two rooms, wrecks them, and from them begins to wreck the rest of your house. You need your house. They don’t. They have one behind that is basically safe and untouched. How long can you endure the destruction before you have to make an unpleasant deal?

These days it’s hard to laugh in the face of the Russian onslaught on Ukraine, but we have to admit that meeting military might with the same is basically destroying the country. As Steven Cohen usefully analogized on the New Yorker Radio Hour, say you live in a big house with 10 rooms. A big bully comes barging in and takes two rooms, wrecks them, and from them begins to wreck the rest of your house. You need your house. They don’t. They have one behind that is basically safe and untouched. How long can you endure the destruction before you have to make an unpleasant deal?

It’s worse of course, because the United States has been up to no good since the fall of the Soviet Union. It’s perfectly true that the U.S. pushed NATO up against the borders of Russia, violated many of the pledges made when the Soviet Union imploded, and have surrounded Russia in a way that is almost designed to provoke a belligerent response. Blowing up the Nordstream gas pipelines (as Seymour Hersch has reported) shows the real U.S. agenda: to push Europe back under its nuclear and economic hegemony. Biden seems like a baffled old man a lot of the time, but this foreign policy is continuous with the priorities of the American establishment stretching back well into the Cold War. We haven’t even mentioned how much money is pouring into the coffers of the biggest war contractors, how much they’re running down stocks of weapons that were nearing their sell-by date, and how this is another goosing of the Military Industrial Complex.

I don’t have time to go on at this moment, so for once I’ll just post this and let it be a brief provocation. (In other news, I have a final first draft of my novel, and it’s being evaluated by a publisher and, separately, a screenwriter! Fingers crossed for good news in the next month or two.)

OK, here’s the long-lost unfinished half hour of our forgotten journey to Eastern Europe in 1990:

And here is the article, written by myself and Michael Whitson (then still using the moniker Med-o), but never published until now!

The Anti-Economy League of San Francisco and Its Heroic, Revolutionary Tour of East Berlin, Szczecin, Gdansk, Warsaw, Wroclaw, and Prague, May-June 1990

We weren’t going to just go over there and be good tourists and take a lot of pictures, NO WAY! We gave our trip a lot of thought and preparation. A couple months before leaving, we settled on our name —“The Anti-Economy League of San Francisco.” First we prepared a leaflet full of broad questions and a bit about ourselves and mailed it to a wonderful mailing list provided by Bob McGlynn of the New York “Neither East Nor West” group.

As we awaited replies we busily produced or acquired an array of goods to take along as gifts when we crossed into the Zone of Consumer Deprivation. We spent several weekends making home-made Anti-Economy League t-shirts and printed up some Anti-Business Cards to go with them. Realizing our new friends wouldn’t have a nearby K-Mart to buy indelible markers, masking and scotch tape, pushpins and thumbtacks, cassettes, and other useful items, we tried to load up on them too. And of course a half pound of precious coffee for each host along the way. Med-o went first, in early April and looped around through Poland, Prague, Budapest, and Zagreb before meeting up with me in Frankfurt-am-Mein back in the West in late May. Along the way he wrote and occasionally telephoned with his impressions. For instance, he wrote from Prague in early May, “it’s certainly true that most urban Czechs are overjoyed to see the Communists out. But, unlike Poland, it’s a different story in the countryside and towns where 75% of the population live. The standard of living has been relatively high there, and that provincial, orderly, stable life (so boring to us) is what most, except some youth, want… Most of those I’ve met in Prague with some pizzazz are liberal artists and/or yearning yuppies. Many are politically progressive—but unable to envision anything beyond ‘The (free-market) Economy,’ or bourgeois democracy. Sort of like home, eh?”

East Berlin

We proceeded directly to Berlin where we met up with Siggi, a veteran of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) opposition centered in East Berlin’s Zionschurch basement, part of the Umweltblaetter group (Environmental or Worldwide Library), and an active member of the editorial collective for Telegraph magazine. For several years preceding the fall of the wall on November 9, 1989, this dark, dank church basement was the main information hub for almost all independent opposition activity throughout the GDR. How odd to imagine in the modern world of fax machines and computer bulletin boards a single point where people had to travel in person to leave and pick up the only oppositional printed material available. The one place that was a sanctuary from the police was this church basement on Griebenowstrasse 16. (Except on·one occasion when the authorities stormed in and confiscated the printing equipment and journals. They also arrested most of Umweltblaetter’s activists over the next few days (see Eastern European Reporter March 1988, Vol. 3 #2).) The basement was generally safe for otherwise illegal publications by virtue of a loophole that made legal anything “For Church Use Only.” As in Poland, the church provided the only space for free expression. Bakunin and Malatesta, to name but two, are no doubt rolling in their graves over the appearance of German translations of their work stamped on the cover “For Church Use Only”!

We met Siggi the first night in East Berlin but had to return to the West by midnight (only a few weeks later, the border was dissolved, and such silly requirements were moot). We reconnected the next evening at the W. Berlin anarchist information center, where we also met up with Marcin Rey from Poland, as well as Till Boetcher, another East Berlin anarchist well known for his long involvement in the opposition. As we crossed the border at Frederichstrasse Station, Marcin (who had been strip-searched at this same site many times) begged Med-o to play his saxophone during the normally officious identity check. After some reluctance, he agreed and we crossed the border with a saxophone serenade that delighted even the sullen border guards (who waved us through without even glancing at·our bulging bags of t-shirts and propaganda).

Siggi, with Till, Marcin and others, gave us a remarkable tour of the squatting scene in East Berlin, which in the last week of May 1990 was enjoying a blissful interlude of relative tolerance and hopeful optimism about the future. According to Siggi, the E. Berlin government published a list in December of 1989 showing buildings available for immediate occupation by people willing to.do the rehabilitation work in exchange for long-term leases. Hundreds of young East Germans, joined by some veteran Western squatters and a number of international friends, were constructing an elaborate subculture of more than 100 squatted buildings.

We visited about a dozen new cafes which had sprung up in these buildings—some were in a very rundown state, but a surprising number had been made into bars with atmospheres to match the ambience of the West. Nearly all were being run by collectives; we were struck by the irony of young anarchists as the entrepreneurial vanguard prior to reunification, even though their new “businesses” were often staffed by volunteers and money was charged primarily to cover costs. The spirit was more oriented toward creation of community than entrepreneurialism. Painting, repair .and construction were underway all around. Slogans adorning squatted walls were a meaningful departure from the rhetoric popular among western anarchists: “Freiheit Macht Arbeit” (Freedom Makes Work) and “Anarchie ist Arbeit—Arbeit an Sich Selbst” (Anarchy is Work; Work on Yourselfl). As one. West German artist explained to us, they often had to postpone their “art” while they worked on rehabilitation, so the slogan “Freedom Makes Work” had a compelling relevance to his daily program.

The squatters had organized an intersquat committee representing over 40 of the 100+ squatted buildings. Weekly meetings had led to a march on City Hall. A several-day occupation of City Hall had led to some negotiated contracts between the city government and the squatters. No one knew what would happen after July 2, whether the West German government would begin a program to return property to its 1935 owners, set up a new city agency to manage the property, sell it to its occupants, or what. I thought it likely that the squatters would be offered to keep most of their buildings as a way of defusing a possible crisis. The biggest problem while we were there was a shortage of inhabitants in each building to defend against increasing attacks from nazi skinhead youth. Bigger armed conflicts seemed to be looming on the horizon as the anarchists began to take self- defense very seriously. In fact, our West German artist contact referred to above was badly burned by a Nazi molotov cocktail attack just two weeks after we visited him.

On another angle, Siggi and his friends had staged an action a couple of weeks earlier when they climbed a 150-meter smokestack over a toxic incinerator and hung a long banner (“transparent” they called it in a charming altered English) down the side urging that toxics not be created in the first place, and certainly not to burn them into the atmosphere. When they climbed down after two hours of carefully hanging it with cables and everything, a morning newspaper was thrust at them by someone in the watching crowd and it already had a picture of their accomplishment. Two days later the police asked Siggi to come down, and when he got there the cops gave him back his banner and sent him on his way. He had broken no laws.

We enjoyed standing on the subway platform and ogling the eclectic mix of wild paintings which occupied the placard spaces previously used by communist party slogans, and now filling up rapidly with western advertisements. The widespread refusal to pay on public transit was great, too. It took me a couple of days not to seek out a ticket automatically before boarding any tram, subway or bus. My observations indicated about 50% of the population completely ignored the honor-system fare collection box. Of course the value of the fare was proportionally miniscule to match the cost of living in the east.

We heard people refer to West Germany as the Elbow Society, in contrast to life in East Berlin, which was quite relaxed and charming in the late May sunshine, especially with the generous, intelligent and witty hosts we enjoyed meeting.

Poland

We left East Berlin for Szczecin, Poland, (pronounced Stchetchin) a 3-hour train ride northeast just across the Polish border. Our train never quite made it to the Szczecin station since a strike had paralyzed rail traffic throughout northern Poland, and the station was closed by strikers. Luckily a fellow in our compartment knew a bit of English and told us what was happening and helped us get into town, a relatively short walk.

The next day we found our friend Robert Swornowski, with whom Med-o had stayed five weeks earlier. He agreed to serve as interpreter and we headed down to the struck rail station with our microphone, video camera and the barely credible claim that we were American TV (I had made up a very authentic-looking press badge indicating I was a producer for “AEL Video Productions” —AEL being, of course, Anti-Economy League!). We passed a couple of dozen hopeful travelers to reach a barricade behind which stood a bunch of blue-clad railway workers. Robert announced our desire to meet and interview some strikers and they had us wait while they went to get someone “qualified” to speak to us. A few minutes later Robert was introducing us to the strikers as from a San Francisco TV station (“Channel 25”— SF’s public access cable station). We were ushered into the office of the guy who was in charge of the Northwestern region of Polish rails. Six feet tall, greying hair, grey double-breasted suit over black shirt and white tie with white shoes, he looked like a mafioso on his way to an important business lunch. We were stuck doing a boring interview with this bureaucrat, but protocol and the fact that he was offering support to the strikers led us to continue the charade.

The strike committee VP whom we met first then escorted us into the meeting room of the strike committee. The men around the room were lost in time and looked as if they could have been from 1905. It was eerie looking into those pained faces with the combination of grim determination and hopelessness that seems to characterize the Polish situation. The committee had voted to allow us in (“American TV”!), but as we entered an older guy got rather upset and announced he was quitting his position as a leader of the strike committee because they had been calling him “fascist” on TV and he couldn’t take it anymore. He wrongly assumed we were Polish. We stayed only about 10 minutes and then interviewed the friendly VP on the abandoned train platform. He recounted the basic story as seen by the strikers:

In the small northern Polish town of Slupsk (pronounced “Swoopsk” and we later learned, the home of a secret police education center), 48 railroad workers had gone on a hunger strike for improved wages (they were making about $45 a month) and structural reforms in the administration of the railroads. After about a month this hunger strike had produced no concessions, and railway workers in other areas began to join the strike, so that now the rails were shut down throughout the northern half of Poland. He emphasized that it was not a “political” strike, that is one aimed at damaging or bringing down the current Solidarity government of Mazowiecki. It was an “economic” strike aimed at improving wages firstly, and administrative reform secondly.

It is important to note that these same railway workers went out in May of 1980, preceding by a few months the explosion that was Solidarity in August-September 1980. They also struck in May of 1988 ahead of the strike wave that led to the round-table discussions and the demise of Communism in Poland. Now they were on strike again, but this time proclaiming it as a narrow economic strike without political intent or result.

Ironically, the strikers were members of Solidarity, but their union denounced the strike, nor was the general population supportive. The strikers were hurt badly by the opportunistic support they received from Miodovich, the head of the union federation created by the martial law regime in 1982. Their denial of their strike’s inherent political meaning was naive at best, since every strike is automatically political, regardless of the intentions behind it. The strike concluded with no improvement for the workers when Lech Walesa made veiled threats that the government would have to take forceful action (implying the possibility of police or military action) to end the strike, and after holding out for an additional week, the strike collapsed.

On the last Sunday in May it was Mothers’ Day in Poland and also the first local election in 50 years. We spent the midday drinking vodka with our host’s mother and her workmate from the post office. Neither of the two 50ish women were going to vote, and neither expected their 20ish sons to live a better life than they had. They emphatically denied any hope in Polish political parties or politicians. Their visions were much more closely focused: what is going to happen to the cost of living? Why should the rail workers get more than the drastically underpaid doctors, nurses, and teachers? We learned that the local elections were for political offices with very limited power—no ability to tax or make budgets and that the scope of these offices had only been defined three days prior to the election. Not surprisingly, there was a high rate of abstention.

Projections expected a low 60% turnout, but the actual figure turned out to be 42%! Before we knew just how disinterested the Poles were in this election we went to the Szczecin Solidarity HQ and asked to do an interview.

There appeared after a half hour or so two nice gentlemen, both from the political (not trade union) wing of Solidarity, one a candidate and the other a campaign manager, both speaking good English. We asked them a lot of questions about the role of the trade union in the government, the splits in Solidarity, what their position was on the rail strike, the future for Solidarity and Poland? They admitted there was no real evidence that the rail strike was being manipulated, but there was no doubt in their minds that the communists were in fact doing so, behind the scenes.

I had to ask them, too, whether they didn’t think Poland was already experiencing a legitimation crisis for representative democracy. With the Polish working class’s remarkable experience of self-organization and direct democracy, might there be a fundamental lack of belief in the institutions of representative democracy? Not surprisingly our Solidarity representatives couldn’t really answer such a sweeping question (who could?). They offered the lame explanation that since voting had always been mandatory under communism, abstention now was the clearest expression of the new freedom in Polish society.

Speculating about how long the Poles would endure the more-severe-than-required-by-the-IMF austerity plan, their guesses were one to two years, but it seemed difficult to believe people would wait so long to object. The average wage of $40 a month was being held in check while prices were rising toward European standards. Previously unavailable oranges were for sale everywhere, but the prices were way beyond a lot of people’s means at 75 cents a pound. In desultory street markets, the newly freed Polish shoppers could choose from a variety of tools, cheap plastic electronic stuff, cheap clothes from sweat shops in Bulgaria and Turkey, and locally grown house plants, produce, and canned vegetables. In late May fresh tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce and onions were commonly available and served in most homes we visited (we later had much less pleasant culinary experiences in Prague… the Czechs hadn’t really discovered fresh vegetables yet in June 1990, but salad bars were surely about to sprout like mushrooms after a rain). We learned that the Polish people do know how to eat well!

Gdansk

Due to the strike we took a taxi ride across Poland, from Szczecin to Gdansk. We worked out a fare of $100; for us it was less than we might have paid for train rides for two across the same distance in western Europe, but for the cabbie it was a months’ normal income.

In Gdansk we were graciously welcomed by the family of Klaudiusz Wesolek(?)—sort of an anarchist nuclear family. Dad was one of Poland’s new self-employed entrepreneurs, an architect, while Mom was a charismatic woman with strong libertarian instincts and ideas. Klaudiusz, is the eldest of three sons (23, 16, and 4) and had just converted his entire family to vegetarianism two weeks earlier. He had been part of a 45-day hunger strike this past winter demanding that local residents be allowed to vote on the proposed nuclear plant for the nearby Baltic coast. A nonbinding referendum was included on the municipal election ballot, and the nuke was rejected by an 80%-20% margin, but Klaudiusz seemed to believe that it would probably be constructed anyway. The deal, being financed by W. German and French capital, calls for the first five years of electricity to be shipped across Poland to Germany. Beyond the radiation dangers inherent in nuclear technology, this plan also requires the construction of massive power lines through the small-farm-dominated Polish countryside-another future flashpoint in the economic “development” of Poland.

Klaudiusz took us to visit Andrzej and Janna Gwiazda, former strike committee members in 1980. Andrzej at one point was one of the top three leaders of Solidarity, but had been pushed out by Lech Walesa, supposedly for being too committed to direct democracy and workers’ control. They live in one of those typical Polish housing blocks, with identical buildings in every direction for miles. Entering the first floor, I felt like I’d entered a U.S. housing project. The two-tone institutional green paint job, with white stenciled numbers on doorways, and an unbelievable stench of urine, struck a certain·universal housing project aesthetic chord. Their tiny apartment, near the top and on the corner, was a very desirable place by Polish standards. People waited 15 years on lists to get allocated an apartment like this! It gave us pause to realize what such housing scarcity would do to the life we’ve known. Also, the difficulty of achieving an independent life for adult children loomed large. Most young Poles we met still live with their parents for lack of other options. So, like Berlin, the question of housing figures centrally in future Polish politics.

We sat and talked with the Gwiazdas for several hours, and they agreed to do a video interview two days later. On the intervening day we stopped by with our questions and went over them with Janna. But on the day we arrived to do the interview, she (Andrzej wasn’t there) announced to us that the interview would be impossible because “You are Communists!”

We were completely flabbergasted, and asked why, and got a big sermon on the printed word. We had left her copies of Processed World, which she apparently had read rather carefully. While liking a lot of it, she took great issue with the interview with peace saboteur Katya Komisaruk, the Vandenberg Vandal herself. Her objection, which was extended to us since were were editorially involved with its production (Med-o was the actual interviewer), was that all the critical talk of the U.S. military without at least a corresponding mention of the perniciousness of the Soviet military proved we were allies of the Kremlin. U.S. militarism was a favorable force in her world view.

In the course of our discussions she had argued that Solidarity was working for the Soviets, and that they weren’t really going to change anything. She said their claims to be for true independence, real democracy and private property were empty lies-she said she wanted a “normal life, with normal things in the newspapers and normal things in the stores,” a goal she imagines can be achieved by adherence to the three pillars of independence, democracy and private property. As an economist, but only well acquainted with the absurd operation of the command economy, she was convinced that a real market economy was the only way to go. She also argued that none of the measures taken so far under the aegis of “privatization” really amounted to any structural changes in Poland’s domestic economy.

Being held so literally accountable for the words of another person, one whom we had published in the context of a rather critical interview, was quite a surprise to us. I’ve often helped things get into print that I don’t personally concur with, but this was inconceivable behavior for the Gwiazdas, and probably for Polish radicals in general. The obvious reason is the wide difference in availability of resources. In Poland, there hasn’t been much room for waste, but then the political situation was much less ambiguous and amorphous than ours in the U.S. People had clear ideas of what they were arguing and why, and it wasn’t difficult to determine whether or not things fit in with the “line.” I think this is less so now, and perhaps there will be a loosening of attitudes regarding such matters after some experience of a free press.

We argued with Janna for a couple of hours, finding it a bit like trying to convince a U.S. Communist Party member that Solidarity was a workers’ organization. Her anti-Soviet paranoia (legitimate.to be sure, but out of touch with reality—Andrzej actually told Med-o on his first visit in April that the U.S. should still be concerned about a sudden Soviet military invasion!) completely muddied her ideas about the world politics.

This may be the worst product of the equally insidious USSR and US cold war propaganda machines—an intolerant, asphyxiated thinking process that can only take in one of two possibilities. It’s either the US (capitalism) or the Soviet Union (“communism”). This idiotic dualism has percolated far beyond the Gwiazdas and claimed the minds of most people the world over. It is the ideological cement that has kept our essentially authoritarian, military-based “democracies” together for the last four decades.

It was depressing to see such a dead-end, one-dimensional world view from radicals who in other ways had a critical analysis of “Polish Perestroika” as a test case for Eastern Europe (and the Soviet Union). They were also very critical of how Solidarity had been co-opted through continual compromises with the Communists and the Catholic Church. Unlike most US anti-communists, it is not the lack of experience with critical thinking but the accumulated paranoia of forty years of Stalinism that has blocked the flexible thinking we usually call “normal.”

One day in Gdansk we were arrested after leaving our usual “droppings” of t-shirts and printed propaganda on a local anarchist’s doorstep. Since he wasn’t home we were standing in the stairwell writing a note to leave with our stuff, when a young cop and a football-sized man in plain clothes walked by. We thought nothing of it until we were meandering away from the building and heard loud voices in Polish behind us. By the time they got our attention we turned around to find the young cop cocking his pistol at our heads! When Med-o was found to have left his passport at the house we were visiting (which under the new laws is no crime), they drove us in their paddywagon to the local jail. There they spent an hour alternately demanding ID from Med-o and threatening that we would have to pay “many thousands of zlotys!” (it was currently 9,500 to the dollar!), then $50 U.S., but finally it was dropped. An older cop (only the younger ones were bald enough to hint about bribes) told us to “GO! GO, Crazy Americanskis!!” So we went.

No one we spoke to had any conceivable explanation for our arrest, and everyone was quite surprised and outraged. Several people suggested they march down there and make a complaint. We later concluded that we had been arrested purely out of boredom. There could no longer be any illegal political conspiracies in Poland, and crime was rather minor, so we got the Kojak treatment mostly because we were “there” and looked strange.

Warsaw

Warsaw is not a pretty city: it is the ugly sprawling “Los Angeles of Poland,” without the posh glamour of Hollywood. Dominated by 20-story concrete block apartments throughout, it’s a place to get out of. We visited with Anna Niedzwiecka, who was a charming hostess. Still in her early 20s, she has already been involved for years with the anarchist and oppositional political scene. She told us about the breakdown in the anarchist movement in Poland. Sectarian splits and bad blood have broken out all over, with some groups no longer even able to talk to each other. It sounded too familiar. Most radicals were stymied by the headlong rush to western-style consumerism surrounding them which quickly changed the rules of the political game they were playing. This wasn’t unique to the Poles, only new. The problem of consumerism afflicts radical politics everywhere. Only capitalist ideology unflinchingly embraces a life of material abundance. Radical visions are usually couched in terms of reduced consumption, less goodies, less self-indulgence, and lurking beneath it all is a basic distrust of people’s desire for pleasure and comfort.

It’s not surprising that people aspire to a high standard of living. The problem is not people’s desires, especially that they desire too much. Our problem, which there is now virtually no way to address socially or democratically in capitalist democracies, is what can the planet’s ecology sustain, and how can we shape our activities so we enjoy the part of our lives spent interacting with nature and other people to meet our needs and desires (presently known in a highly perverse and distorted form as “work”)?

Anna took us on a walking tour of Old Warsaw, made sure we tasted the local specialty Honey Wine, and hung out discussing all these big questions with us. One day she took us to a planned demonstration at the State Prosecutor General’s office, a building situated near the Old City and in the middle of the hangout area for heroin addicts (yes, Poland has thousands of addicts, mostly using locally grown and refined heroin, many of them HIV-positive and begging on the streets). The protest demanded the release of an anarchist who had been jailed two weeks earlier after allegedly participating in the firebombing of the Soviet consulate in Cracow (southern Poland). The firebombing had been an unplanned outgrowth of another protest over the death of an anarcho-syndicalist in a Soviet prison that May.

On this day a crowd of 20 mostly teenage, scraggly Warsaw anarchists gathered only to learn that he had been released a few days earlier. With that demand now meaningless, they grabbed our t- shirts and began handing out our Polish language anti-business cards to passersby in downtown Warsaw, which for us was a wonderful fulfillment of a fantasy, and for them a lot of fun, too.

Wroclaw

Wroclaw (pronounced Vrahts-wahv) used to be the German city of Bresslau, and its German past makes it a more physically attractive place than most Polish cities. It’s much greener and the architecture is considerably less block-like and obnoxious. Our hosts were Hanka and Wiestof and their 2-year old daughter. They had been active with the Orange Alternative in the couple of years preceding our visit, but the OA is in a state of limbo now. We had hours of fascinating discussion with them, and they walked us around town, explaining the recent history of the local movement, now in hibernation.

The Orange Alternative was once thousands of people from Wroclaw who filled the streets in 1987-88, in a dramatic break with the fear that had been paralyzing Polish society since martial law was declared in 1981. Unlike any protest groups before them, they integrated humor, theatrics, and psychological liberation into their call for broad social changes. One of their bigger campaigns was to “Free the Smurfs.” Another one featured 9 people wearing t-shirts bearing one letter. When eight of them stood together, their message (during a big heat wave) was “Stop the Weather!”, but when the ninth person stepped in and added a letter, the message changed to “Stop the Police Clubs!” Their actions were designed to pre-empt police repression by avoiding overtly disallowed political stances. A moving force within the Orange Alternative was a fellow known as Major. He ran a mock electoral campaign under the slogan “A Red General or an Orange Major—Relax! It’s Your Choice!” They also printed and widely distributed posters of “General Jaruzelski: Wanted Dead or Alive—$1,000,000 reward!” Their political protest is stylistically very similar to many political protests in the U.S. and Europe during the past two decades, relying heavily on humor, irony and the disruption of social conventions accepted as “normal.”

A friend played music he and others recorded in an abandoned giant underground military tunnel (hundreds of kilometers of tunnels lie under western Poland—built by the Nazis in WWII—large enough to drive tanks through), a wildly eerie sound. They go down into the tunnel for 3 days to 2 weeks at a time, take hallucinogens and play music. We were intrigued, but without several days and a car we couldn’t visit the place.

We visited Wroclaw for a couple of days, and then left Poland. After 10 days in Poland (Med-o had been there for 2 1/2 weeks in April as well) we were ready to go on. Active opposition was in a state of disarray, and we too felt stymied by the predicament of the Poles. We certainly couldn’t offer practical answers when Poles perplexedly asked us what Poland should do. I could only see the two extremes: slavish obedience to the West/IMF (which is being attempted with certain qualifications) and an autarkic break with the world economy and an attempt to forge a debtor’s cartel and an alternative non-economic . system. What would that look like? How would it work? What countries could Poland turn to participate in such a grandiose plan? We didn’t have such answers. Few Poles want to experiment again after 40 years of the Communist “experiment.” They want the tried-and-true fantasy of free market capitalism, a deception that “works.”

We sure liked the Polish people. The vibrant spirit and lively energy are forces to be reckoned with. Maybe after a few years of trying to conjure up a West German standard of living in Poland, they’ll want to try something different. Like most of the east bloc countries, they’ll have to overcome a basic racism that makes them think that because they are white Europeans, they should be able to achieve a western standard of living. When discussing the market and the economy, the U.S. and Germany are the models, not Brazil or South Korea or any of the many highly stratified and exploitative societies characteristic of Capital in most of its domain.

Prague

Our stay in Prague coincided with the June 9th national elections—the first free, multi-party elections since before the 1940s. Med-o had passed through earlier and found it very difficult to make contact with radicals, since so many of the known oppositionists were now involved in the government and election campaign.

Instead he had arranged to have the crazy Russian in the English section of Radio Prague to be our guide and host. Misha had lived in New York from age 8 to 13 and quickly proved himself to be the most complete chameleon I’d ever met. He is a heavy drinker, like Russians are generally reputed to be, but maintained a rather European lucidity with the right amount of alcohol coursing through his body. He adapted to our syntax and pronunciation even quicker than he tuned in to our political views and style, but he managed that too.

Seeing Prague, the Civic Forum, and the elections through his (and his Czech wife Maika’s) eyes gave us a pretty different slant on things. Maika had been a member of the Communist Party since 1980, when, at age 20, she joined at the behest of her more elderly coworkers at the post office. She had recently lost her job when the Lenin Museum permanently closed down, and her studies in Marxism-Leninism had been rendered moot. My impression after five days was that she had no attachment to M-L-ism per se. Through her personal experience she was already deeply suspicious of the Civic Forum and was suffering the fate of the dispossessed. No job, no future. She had studied Russian in Kiev (Ukraine, USSR) for five years (in large part to be with Misha), and then they married, and moved 25 kilometers outside of Prague on the commuter train line. (Misha’s father, once stationed in New York with the Soviet UN delegation, lost his diplomatic job and was banished to a lowly professorship the day after Misha married Maika, since she was not Russian.) She worked at the Museum while he worked at Radio Prague.

Misha had survived the first round of purges at Radio Prague thanks no doubt to the overwhelming fact that he was naturally anti-authoritarian, regardless of whom was in power. Because of their pessimism about future life in Czechoslovakia, and their fear of being blacklisted for their background as survivors (and beneficiaries in some small way) of the old regime they fantasize about moving to another country.

Misha helped us interview a number of politicians and people on the streets. The chairman of the Czech Green Party, for instance, explained how Czechoslovakia would have to continue using nuclear energy until the economy was converted to a free market. The market economy was a prerequisite for improving environmental conditions in general. The chief editor of the Social Democratic Party’s newspaper explained how Austria was a good example of how Czechoslovakia could be, and a Social Democratic Party as big as West Germany’s could help engineer a strong national economy. Many people on the streets defined democracy as the absence (and even banning) of communism and communists. A woman in a park with her baby, an economist on 3-year motherhood sabbatical, was an exception, as she quoted Vaclav Havel’s rejection of collective guilt.

Generally we found the level of political discussion in Czechoslovakia stunted. There was very little disagreement about “returning to Europe” or moving to a market economy. Like Poland and East Germany, a popular fever for the West was quite tangible. How interesting it will be in two or five or ten years to see how people are feeling then. No doubt some people will prosper and generally everyone will feel somewhat richer just being surrounded with the images of commodities if nothing else. But the desperate fantasy that so many of its citizens seem to harbor about an economic boom in eastern Europe with its opening to the West, is a bubble that is sure to burst. Will the racist and reactionary tendencies in that part of the world become ascendent in the unstable climate ahead? It’s impossible to know, but the fantasies of shopper-filled malls and a New Prosperity can’t last. The question remains, what will replace them?

—Chris Carlsson and Med-o (Michael Whitson)

Leave a Reply