A luxury tech bus graveyard near the SF dump on Tunnel Road! (probably they are just parked there when not in use)

Once again I’ve left my blog languishing. I have a better excuse than usual. I’m working on a new novel! Have about 75,000 words written so far, and probably as many more to come. I hope to wrap up a first draft sometime in summer, and then there will be the rigorous purging and rewriting… we’ll see how it all goes. But the good news is that so far I’m having fun. I got past the beginning slog, and now the book is just coming to me every time I sit down to write. I always have a chapter or two in mind and just go into the moment and let the story unfold. It’s a blast when it flows like that.

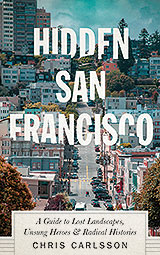

That said, I still carry on reading all sorts of fascinating books, some of which should help my character and scene development in the novel (sneak preview: it’s set starting in 2023, but mostly later in the mid-2020s, finally ending in 2050, working title is “When Shells Crumble”—it was supposed to the prequel to my 2004 novel After the Deluge but it has shifted too much and I wouldn’t characterize it that way anymore… though there are a few connective tissues).

And I also can report that I am continuing to be cancer-free. The melanoma has not reappeared and I just had my every-three year colonoscopy and it didn’t turn up anything worrisome either, I’m happy to report. I have had a weird shoulder/upper arm injury that has persisted for several months now. I just had a great therapeutic massage today and am optimistic that a new approach to my daily exercise and posture may help me recover sooner than later. I have had to give up weekly frisbee throwing (that’s probably how I hurt myself in the first place) but continue to enjoy petanque, and can’t help but love having my granddaughters leap into my (aching) arms! I’m on Medicare now, which is a much worse deal than the CoveredCA deal I had until I turned 65 a month ago. But it’s better than nuttin’.

The Russian attack on Ukraine is dominating the headlines and pushing out of sight the dire humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan imposed by the US impounding billions of their national assets. Rendered invisible also are the ongoing catastrophes in Yemen, Gaza, Sudan, Somalia, etc., all fueled by US arms sales and political support for barbaric regimes. Meanwhile climate refugees are fleeing violence and collapsing ecologies in Central America, northern Africa, and other regions, all of which is driving the rightwing xenophobia that continues to gain political momentum. It’s a bad time on ol’ Planet Earth!

This building on 25th Street a few blocks from my house is organized against being evicted by way of California’s evil Ellis Act.

Price Wars is a new book by Rupert Russell, an enterprising journalist who decided to visit many of the most problematic spots on the globe to see what was driving the crises. He visits eastern Ukraine, exactly where the new Russian attack is unfolding as I write. He goes to Kenya and Guatemala too. But his main point is that prices, that seemingly neutral outcome of market transactions based on supply and demand, are anything but neutral or “natural” (as the neoliberals tend to argue). He details the role of speculation and derivatives in driving all sorts of price dislocations (in energy, food, and other basics of modern life) which completely separate prices from their signaling function, and instead become a means of deceiving large numbers of people while a very small number of people are pocketing vast social wealth.

It is the collectively shared perception of reality, rather than reality itself, that drives prices.

p. 171

Their irrationality serves a rational interest. It is how those who sit atop the market pyramid are able to transfer wealth from others to themselves. It is precisely prices’ inefficiencies and inaccuracies, their ability to manipulate, hide, amplify and narrate that makes them engines of enrichment as well as engines of chaos… The market mythologisers have deployed the same tactic. As I had seen again and again, migrants had played a pivotal role in keeping the would-be reformers at bay. The Feed, filled with the “rapist hordes” and “invading caravans,” served up ready-made scapegoats, deflecting attention from the inscrutable financial alchemy to the photo-friendly “barbarians at the gate.”

p. 239

In my previous post I discussed in depth various aspects of our militaristic society and the omnicidal impulse shaping the colonial logic that has spread across the planet for the past five centuries. I read Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War by Howard French (Liveright Publishing Co., W.W. Norton & Co., 2021). French is a longtime New York Times reporter, which doesn’t necessarily establish much credibility in my mind, but this is a wonderful book. It helpfully backs up the “beginning” of our timeline to decades before Columbus’s 1492 voyages to the Caribbean. He recounts the tale of a prominent king from Mali who traveled in the early 1300s to Mecca by way of Egypt and gave away several hundred tons of gold along the way to prove his power and wealth. Stories of this gold-laden monarch and his kingdom in Africa made it to Europe and sparked early Portuguese exploration voyages along the West African coast decades later in the early 1400s. Our common histories have portrayed Portuguese exploration as a brief sojourn along West Africa before one of their explorers finally made it around the southern tip of Africa and “discovered” the Indian Ocean, eventually establishing trading posts in East Africa, India, Malaysia, Indonesia and China (Macau). French corrects this deeply deceptive account. Actually it was a slow process, taking many decades, before that journey around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean. During those decades Portuguese traders gained preferential access to gold trading first, and then trading in black humans in West Africa and eventually further south in what is later Angola. With this early trade in gold and slaves, the Portuguese state became one of the wealthiest in that period, eventually taking over the island of Sâo Tomé where they pioneered the sugar plantation using slave labor (this followed the heavy exploitation of the Atlantic island of Madeira, and then later the Canary Islands). The integrated sugar plantation was then transplanted to Portuguese colonies in northeastern Brazil before finding its full barbaric development in the Caribbean under Dutch, British, and French control more than a century later.

São Tomé’s plantations, in other words, were designed for and run exclusively on the basis of violent domination of Black African slave labor. This would prove to be the indispensable killer apparatus of modernity. And it was from the harbors of São Tomé that the model soon spread to the New World, with all of the grotesque inhumanity inherent to it.

p. 116

He continues his argument later in the book to expand his main point. Not only was African slavery essential to the growth of early European states and economies, it is at the very heart of modernity and our sense of what “The West” is.

The most important contribution of African slavery to the West … was something far larger and yet hiding in plain sight, something in fact that is indisputable: Africa, and the human resources drained from that continent via the greatest forced migration in human history, provided the most essential input of all by far to making the New World economically viable. Africans, in other words, became the ingredient sine qua non in this vast project… The Atlantic world was not just made viable through their labor. Yes, as we have claimed here, it was this appropriated toil that generated nearly all of the commodities and much of the gold and silver that helped fuel the ascension of the West. But that is not all . Far from it. More important still, it was the very founding of this Atlantic world, an unprecedentedly large geographic sphere spanning four continents, that created what we now think of and understand as the West, and this is what made the very greatness that we associate with this geographical notion possible.

p. 223-224

Moreover, being published by a mainstream publisher like Norton in New York City, and written by a New York Times reporter, this book is a great example of how much the crazy right has lost control of the boundaries of American history. Their fervid attempts to block Critical Race Theory and ban talk in schools of race or gender will look in retrospect like the absurd attempts to halt the march of history that they are. French’s book surprised me by relying extensively on some of the excellent books that I read in the past couple of years and blogged about earlier, like Walter Johnson’s epic tale of St. Louis, or the role of undocumented oral transmission in passing news of revolution around the Atlantic world, or the role of cotton slavery as the source of time-and-motion managerial thinking, or the use of “predatory inclusion” by HUD and private lenders to further drain black Americans of generational wealth during the 1970s official “desegregation” of housing. French knits together much of this new historical work to bolster his deeper argument about the fundamental role of black Africans in the creation of the modern world.

In developing some of these arguments, I have drawn heavily upon the work of the recent generation of historians—some of them quoted or cited here, and many others who are not. Taken together, their research has offered new clarity and depth about the ways in which the rise of the United States was predicated directly on slavery and especially on the wealth generated by the cotton-growing South. This ongoing revolution in historiography has helped overturn a number of long held notions, some of which border on a denial of slavery’s fundamental economic importance to America.

p. 392-393

But new scholarship has shown that the “peculiar institution” played a pioneering role as a source of innovation in management, an avatar of modernity if there ever was one; indeed, this occurred well before the railroads were given credit for this by the famed Harvard scholar Alfred Chandler, who called them the initiator of the “managerial revolution.”

p. 410

The story of slavery, of plantations, and of the Black labor that generated the most important product of that era, cotton, is by any reasonable standard a core element in this immense human change [industrialization]. But that is not all: the economic activity that surrounded cotton also lifted banking and insurance and drove globalized commerce on scales never seen before.

p. 416

All of this is to underscore the strange disconnect between the burgeoning expansion of deep histories that rip away the veneer of self-congratulatory bullshit that has been spooned out by American and European historians for a century, and the frantic efforts of right-wing politicians to stamp out these new understandings and insights.

At our recent walks on San Bruno Mountain we saw some beauties… David Schooley said this was a Mission Blue but since it was on a Ceanothus I still think it was an Echo Azure.

There were tons of these Variable Checkerspots!

Finally, the last book I want to highlight is by two friends, Rupa Marya and Raj Patel. I’ve known both for years now, and have enjoyed their respective evolutions, Rupa as an activist doctor and anti-racist campaigner as well as an inspiring rock musician (Rupa and the April Fishes); Raj is a brilliant writer with a sharp sense of history, whose books run parallel to much of my own work (especially The Value of Nothing and The History of the World in Seven Cheap Things cowritten with Jason Moore). He also makes movies and teaches! They cowrote a new book Inflamed: Deep Medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, NY: 2021), which is simply essential. Of the gazillions of self-help and alternative medicine books, none of them ground their analysis in this kind of systematic critique of the context, both historic and contemporary, in which medicine (of all types) is practiced. Key to their analysis, beyond more familiar categories like racism and colonialism, is the idea of the exposome.

Damaging exposures are the game changer, converting our aging cells into ones that do us harm. The sum of lifetime exposures to nongenetic drivers of health and illness, from conception to death, is called the exposome. The exposome encompasses chemical, social, psychological, ecological, historical, political, and biological elements that determine whether aging cells will become drivers of chronic systemic inflammation.

p. 32

The book is full of amazing facts (like in 2005 there was 1930 metric tons of human-generated mercury vapor on earth!), but what really worked best for me was the lyrical writing that managed to always recenter deeply historical and political contexts when thinking about the inflammations that characterize most modern illnesses.

Humans are not little states with their own border patrol but assemblies in a web of life… Medicine has come to understand the emergence of disease through the metaphors of war and tolerance because these were the liberal and neoliberal political metaphors at hand.

p. 49 and 50

I was reading along when up popped a reference to my own recent bout with metastasized melanoma.

Another example of immunotherapy is the use of IL-2, a cytokine that expands certain T cell populations in a specific subset of patients with metastatic melanoma,a deadly skin cancer. Lifespans increased for people with what was formerly seen as an untreatable disease.

p. 57

This short reference reminded me of reading the New York Review of Books some months ago, curiously delving into an article by physician Jerome Groopman on how the microbiome works (the word that refers to our gut and all the millions of other beings that live there and help shape our well-being, our moods, and much more).

Last February two reports appeared in the journal Science that moved research on the microbiome an important step forward. One report was from the Sheba Medical Center at Tel HaShomer, Israel, the other from the Hillman Cancer Center at the University of Pittsburgh. Both concerned clinical trials on manipulating the microbiome in patients with metastatic melanoma. Until recently, melanoma that had metastasized widely in the body was almost always fatal. But over the past decade a therapy was developed that causes immune cells to attack cancers, resulting in the survival of between 20 and 40 percent of patients. (The researchers who provided the groundwork for this treatment were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2018.) Conversely, some 60 to 80 percent of melanoma patients treated with immune therapy do not benefit from it. There is little else doctors can do for many of them.

I am in the 20-40% happily. I was cured by the immunotherapy, maybe because I have a very healthy diet of fresh, mostly organic foods. Or maybe because I live in San Francisco where the air and water are relatively clean? Who knows? But the treatment I got was only authorized for this use in February 2018, and I got it in August 2020. When the surgeon gave me the pathology report a week after my October surgery, he told me they found only dead cancer cells. It seems the treatment had vanquished it prior to the surgery! So for me it was a miracle drug that killed off my stage 4 cancer in 3 treatments that boosted my own immune system’s T-cells to attack this particular cancer. So I don’t take modern medicine lightly or for granted. I’m a lucky beneficiary. That said, the critique Rupa and Raj have put together should be read by everyone. One of the crucial pillars of their analysis is a frank and humble appreciation for ancient knowledge carried through to the present by indigenous peoples across the world.

Indigenous communities should be understood not so much as “artifact[s] from the past but as instructions for the future.” They are not relics of lost or destroyed civilizations. On the contrary, they record in social memory the successful technologies of the planet’s most resilient human survivors… Listening is a skill that is neither honored nor modeled in a medical system in which the primary focus of the doctors’ gaze is the screen on which they transcribe and code the record of symptoms. The rise of big data in medicine doubles down on the idea that the patient’s words are mere noise hiding a signal, rather than a speech act in a dance of mutual knowledge and vulnerability. Listening require humility, to acknowledge a state of not knowing.

p. 175 and 178

Curious art on the wall in the neighborhood.

Ultimately, if we take their analysis to heart, we can no longer hold on to our powerfully egoistic sense of self. We are comprised of literally millions of lives and the boundaries at the edge of whatever it is we think of as our self are extremely fluid.

Individual organisms are constituted in mutualism and exchange in which the borders between self and other are fluid. That we have failed to appreciate the significance of this web of life reflects on the individualist strain in the human sciences, the sciences borne of modern liberalism. If your biological theory allows you only to look for individuals, then the research technology you’ll develop as a result will be very good at investigating individuals. But if your theory is different, the world is cracked open… While the last century’s frontiers of biology focused on the gene, this century is defined by its fascination with systems, from the gut microbiome to neural networks. Both of these systems impact the biology of the mind, which is not located simply in the brain but is a composite of phenomena that occur throughout the body—an oscillating identity, fully embodied but not restricted to one site.

p. 299 and 301

Just in the same way that the histories I been reading and writing about, and that French based his own book about Blackness and modernity on, Inflamed confronts us with the origins of the paradigms that shape our sense of self, our sense of well being, and even the relationship between individuals and history. The entirety of our surroundings shapes us as much as genetics is imagined to do, in fact, much more. Understanding that medicine is no more neutral or natural than the prices analyzed by Rupert Russell is one more building block of a new way to understand life more broadly. This book is a great contribution to the larger process of unpacking colonialism and omnicide by locating it in the unlikely intersection of our bodily health and the industrial provision of medical care. Check it out!

A sunset from my back window… one of my ongoing pleasures in every day life!

Here’s David Schooley talking to some of the Shaping SF guests on our recent hike up Owl Canyon on San Bruno Mountain… thanks David!

If you never walk up San Bruno Mountain you won’t know that there are amazing dense oak forests up there!

Great blog post. Always appreciate your literature reviews

Brilliant column. Well-written, highly informed exposition upon notable books. You sure you’re not cheating the Internet by writing here so infrequently?