Had to put a nice photo first… this is on the Bay Trail north of Carquinez Strait looking east/southeast towards Mt. Diablo on May 4.

Art Hazelwood produced this poster to help promote unionization among the adjunct (visiting) faculty at the San Francisco Art Institute

I have been teaching college classes at the San Francisco Art Institute since 2011, and just cast my vote to join SEIU 1021 in a current union election campaign to organize all of us “temporary” teachers (i.e. visiting faculty, adjunct professors, etc.). Adjuncts at Mills College over in Oakland just voted 68-19 to join the same local, and soon our colleagues at the California College of the Arts will be voting too. There’s a huge nationwide push on among adjuncts to unionize and I’ve been getting steady news about it all thanks to Joe Berry’s excellent email newsletter for COCAL (the Coalition of Contingent Academic Labor).

There’s no small irony for me in this moment and this vote. I trace my own involvement with organized labor back to the mid-1970s when I volunteered to work on the UFW lettuce boycott in 1974 in Oakland, and was actually fired from Books Inc. in Santa Rosa at the end of 1977 for supposedly trying to start a union there. (Actually I had knocked on the doors of the Retail Clerks Union one floor above our bookstore in Coddingtown Mall, but they had never been there and had not responded to my phone message. Writing a letter to the chain owner asking for a 15% store-wide raise–after a 41% increase in December sales from 1976 to 1977–led to my firing by the store manager before my letter was ever delivered. I contacted the National Labor Relations Board and they got me a two-week back pay settlement some months later, and Books Inc. posted signs in all their 27 stores promising not to interfere with “protected concerted activities” which my meager effort was). Later I volunteered on the JP Stevens boycott, and did minor support work on the UMW Coal strike in 1978 and the OCAW refinery strike in 1979. This was the same period in which I read Marx, and met up with the Union of Concerned Commies.

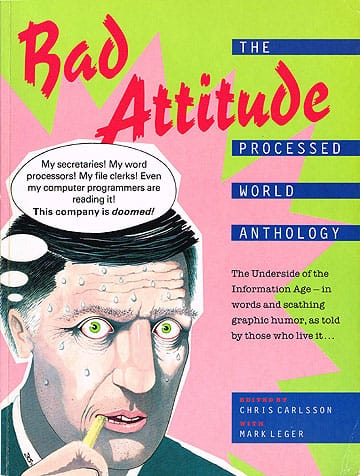

By fall 1980 we were working on the first issue of Processed World. We wanted it to be a place for “dissident office workers” to write, to joke, to share ideas, and create bridges among workers and workplaces across various geographic, class, racial, and ideological boundaries. The Old and New Left were still very much part of the scene in 1980, and we were convinced that Jimmy Carter was as far right as the U.S. could possibly go, so we were not very worried about Reagan having any chance of winning the election that fall. (A great history of the period 1968-84 is in Jefferson Cowie’s “Stayin’ Alive: The Last Days of the American Working Class“–in it he convincingly shows how Nixon was the last New Deal president, and Carter was the first neoliberal president, meaning it was Carter who put in motion the shattering of the old labor movement, the deregulation and privatization agenda that we saw Reagan/Thatcher radically deepen and accelerate, etc.). In the first issue of Processed World we got to cover the largest ever private sector white collar strike in San Francisco at the Blue Shield health insurance offices around the city. Office and Professional Workers (OPEIU) Local 3 was the union, about 1100 workers were on strike, mostly women of color (we learned much more about the strategic leverage they had–and didn’t use–several years later when a new Processed World contributor told the story he saw as a consultant to the white male managers who were utterly clueless about how the work was conducted by their female workforce).

The Blue Shield strike was at that big turning point just before Reagan fired all the air traffic controllers. But it was a harbinger of what was taking shape. OPEIU Local 29 over in Oakland was on strike at the same time, against Blue Cross, and facing much the same set of demands and possibilities as their colleagues in San Francisco facing Blue Shield. Rather than maintaining a united front, Local 29 settled for a very weak agreement in the middle of the strike, completely undercutting the bargaining position of Local 3. Simultaneously Local 29’s own members were on strike against the East Bay AFL-CIO Council of Building Trades Unions who were denying them cost of living wage increases! Building Trades Union bureaucrats blithely crossed the picket lines daily of their striking secretaries and other office support staff. This everyday business unionism was so taken for granted that none of these raised much of a ruckus at the time. By the time OPEIU Local 3 settled the Blue Shield strike in 1981, only 150 workers returned to work, and the terms of the deal were more or less what had been offered at the outset of the strike. It was a devastating defeat, but by April 1981 there was Local 3 representatives on stage in Justin Herman Plaza on National Secretaries Day crowing about the great “union victory” their miserable strike had produced!

We covered many strikes and other labor issues over the years in Processed World and it was remarkable how consistently the unions would aggressively impose bad contracts on their members during this period of capitalist restructuring. Could they have bucked the trends at the time? As willing participants in the capitalist economy, with personal stakes in the maintenance of their own privileged income and access to universities, country clubs, etc., probably not. But by staying fully within the logic of a narrow business unionism, seeking only the best deal for the existing members, class-wide solidarity (never very strong in the U.S. anyway) was routinely repudiated as a strategy. The legally allowed tactics for the shrinking number of organized workers to defend themselves made sure they would keep shrinking, and watching their standard of living deteriorate, or at best stagnate, while the owning class took more and more (all this is well documented by now in the burgeoning research bolstering the 1% vs. 99% occupy meme).

We even discovered an interesting alternative history of a different kind of union that appeared among social workers in the period 1966-75, that had to break away from the existing union (then Building Services Employees International Union Local 400). Of course the social climate was quite different in that era than in the 1980s, but it was fascinating to find a working example of a horizontalist, transparent, democratic union that refused to sign contracts, that understood its strength as based on the daily exertion of power by its members at the workplace.

Which brings me to a great book I just finished by Frank Bardacke called “Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers.” (Interesting overlap here too: Cesar Chavez’s tactics were invoked as an inspiration for the organizing that some people experienced as invasive and harassing. During the campaign to organize adjunct professors at SFAI some SEIU organizers went to people’s homes, causing at least a few to object and to feel they were being stalked–even though by all accounts the organizers were perfectly polite and left as soon as asked. In explaining it during an online discussion a couple of pro-union teachers pointed out that this is a technique that Chavez and the Farm Workers employed during their early organizing days in the early and mid-1960s–which was derived from Saul Alinsky’s model of community organizing.) Anyway, Bardacke is a long-time radical who spent many years writing this incredible history of the Farm Workers and the whole decades-long experience in the Central Valley grapes, in the Imperial Valley, in Salinas and Watsonville, and beyond. He provides a painstakingly detailed history from the beginnings of Chavez’s organizing efforts when farm workers had no rights, were not under the National Labor Relations Act (it passed in 1935 in part by excluding agricultural workers from its provisions), and were living and working largely at the mercy of ruthless farm owners, some of whom were in the midst of upsizing into organizations that preceded the massive agribusiness corporations of today.

Which brings me to a great book I just finished by Frank Bardacke called “Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers.” (Interesting overlap here too: Cesar Chavez’s tactics were invoked as an inspiration for the organizing that some people experienced as invasive and harassing. During the campaign to organize adjunct professors at SFAI some SEIU organizers went to people’s homes, causing at least a few to object and to feel they were being stalked–even though by all accounts the organizers were perfectly polite and left as soon as asked. In explaining it during an online discussion a couple of pro-union teachers pointed out that this is a technique that Chavez and the Farm Workers employed during their early organizing days in the early and mid-1960s–which was derived from Saul Alinsky’s model of community organizing.) Anyway, Bardacke is a long-time radical who spent many years writing this incredible history of the Farm Workers and the whole decades-long experience in the Central Valley grapes, in the Imperial Valley, in Salinas and Watsonville, and beyond. He provides a painstakingly detailed history from the beginnings of Chavez’s organizing efforts when farm workers had no rights, were not under the National Labor Relations Act (it passed in 1935 in part by excluding agricultural workers from its provisions), and were living and working largely at the mercy of ruthless farm owners, some of whom were in the midst of upsizing into organizations that preceded the massive agribusiness corporations of today.

Chavez’s earliest effort was to end the Bracero program, a federally organized system of bringing cheap contract labor across the border from Mexico to work in the fields of California and Arizona that started during WWII, a phenomenon which perpetually undercut efforts to organize and improve conditions for U.S.-based farm workers, citizens and residents alike. About the time the campaign succeeded at getting the Bracero program ended, the first grape workers’ strike erupted in Delano in the Central Valley in 1965. Chavez was opposed to the strike, but out of the complicated failure of the actual strike arose the remarkably successful years-long boycott campaign. Chavez brilliantly used religious iconography, a hundred-mile-long pilgrimage from Delano to Sacramento, hunger strikes, and a range of nonviolence-based tactics to galvanize public opinion to support the farm workers. Focusing in 1969 on pesticides, in particular aerial DDT spraying of grapes AND farm workers, helped raise the profile of their campaign among U.S. consumers (and eventually helped produce a big market for organics, but that comes many years later). Chavez made a strong relationship with Robert Kennedy before his assassination, then later with Jerry Brown during his first governorship, and found an accommodation with George Meany’s AFL-CIO, eventually agreeing to turn his organization into a normal union.

Bardacke has pored over the records of the union and its predecessor organizations, following the organizing, the volunteers, the lawyers, the money, and the politics and evolution of the UFW and Cesar Chavez. Many myths are dispelled along the way and a great deal of dirty laundry is aired out in the plain light of day. The deification of Chavez since his 1993 death, including a statewide holiday here in California on March 31 every year, has helped reduce the complicated dimensionality of Chavez the man, and has helped sweep under the rug many of his uglier actions over the years: the ruthless top-down purges of union stalwarts he repeatedly engineered, the disdain and disapproval he often seemed to have for actual farm workers taking action on their own, his bizarre embrace of the cult-ish Synanon and its semi-secret “Game” that he used inside his Executive Board to ferret out disloyalty and isolate dissent, and his paradoxical embrace of a strident anti-immigrant position for many years (from p. 488-89):

In May 1974 a memorandum from Cesar Chavez to all UFW “entities in California, Arizona, and Florida” announced “the beginning of a MASSIVE CAMPAIGN to get the recent flood of illegals out of California” (emphasis in original). The memorandum was clear: “We consider this campaign to be even more important than the strike, second only to the boycott. If we can get the illegals out of California, we will win the strike overnight. This campaign, therefore, is our number one priority here in California, and we expect all Union entities to cooperate to make it successful.”… In the six months that followed, until December, when the campaign was officially ended, there is no record that any member of the Executive Board registered any reservations about what became an organized, systematic attack on undocumented workers, nor did any Executive Board member subsequently interviewed remember criticizing it.

Scapegoating illegals had been part of the tool kit of the union in all of its incarnations–National Farm Workers Association, United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, and United Farm Workers of America–since 1965, but the scale of this new campaign was unprecedented… The illegal invasion of the fields became a main subject of Chavez’s speeches, the primary focus of most UFW press releases… UFW literature accused illegals not only of taking jobs and dooming strikes but of bringing disease into California… Boycott offices were also involved. They collected more than 40,000 signatures on a petition calling on the Justice Dept. and INS to enforce the immigration laws and to remove the “hundreds of thousands of illegal aliens now working in the fields.”… When the government wouldn’t, or couldn’t, sufficiently execute deportations, the union took action itself, fielding an extralegal gang of a couple of hundred people who policed about ten miles of the Arizona-Mexico border, intercepted people attempting to cross it, and brutalizing the captives.

Some things are only understood in retrospect, but that cannot be said about the UFW’s Campaign Against Illegals. Plenty of people recognized its risks. They argued that the campaign reinforced the differences among farm workers rather than trying to unite them; they complained that the call for increased Border Patrol raids seemed to ally the UFW with the migra, one of the government agencies most hated in the fields, even among legal workers. The campaign was politically and ethically reprehensible, the critics said, and it would hurt the union’s support among farm workers.

Given the dark history of white racism that dominated the labor movement in California for a century from the 1850s on (only being broken in part by the Marine Cooks & Stewards Union and the Longshoremen in the 1930s), it’s perhaps both understandable and befuddling that Chavez and the Farm Workers would take such a wrong-headed stand against “illegals.” As Bardacke ably points out, it’s even more amazing when you consider that they were living through one of the greatest and most obvious demographic shifts in recent history:

When the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) was founded, in 1962, California farm workers had been a diverse bunch: braceros, Filipinos, whites, blacks, Tejano migrants, Mexican migrants (documented and not), Mexican American migrants, and settled Mexican Americans. Although the braceros did much of the stoop labor, dominated vegetable harvesting, and worked in several tree crops, domestic farm workers still played a significant role in the table grapes and many other crops. By the mid-1980s, when the UFW was defeated in the fields, less than 10 percent of California farm workers would be native-born, and more than 80 percent would be born and raised in Mexico. At the time of the union’s attack on the undocumented, this trend was already making headlines in the mainstream press. (p. 490)

In 1974 the UFW was still, conceptually, a union of legal, domestic farm workers. That is how the union defined itself. Most of its leadership came from that group; so had most of the farm workers recruited onto the staff… Chavez… automatically thought of the jobs in the fields as belong to legal Mexican American farm workers, people who came from the same background as he. He thought this even though, since the loss of the table grape contracts, most of the unionized jobs in the fields were not held by Chicanos, and the majority of UFW members were Mexicans, either green-carders or undocumented workers. That fact had not changed the UFW leaders’ image of their union. (p. 493)

In 740 pages you can learn a great deal about the history of farm work in California, how different vegetables and fruits are harvested, what the relations are like among the people doing the work, where and when different crops grow, who the companies were that the farm workers faced in their efforts to gain a then-standard U.S. working class (i.e. middle class) wage, and more.

I love Bardacke’s descriptions of how the lechugueros (trios of lettuce cutters and packers) would work together producing finished cases of iceberg lettuce, how the celery is cut and stacked, how the lemons are picked. We eat all these things all the time and have so little knowledge of the strenuous manual labor that goes into getting us a beautiful stalk of celery for two bucks, or those heads of lettuce for less than a dollar. It doesn’t end well, this story of the remarkable rise and fall of the UFW. The union still exists today but faces a radically redesigned and globalized food production industry. The workers in the fields are largely immigrant workers, documented or not, and many have bad memories or knowledge stemming from past conflicts–whether between legal and “illegal” workers, between Mexican Americans and Filipinos, between UFW and Teamsters organizations, etc. The gains that were won in the 1970s were mostly lost by the mid-1980s and have not been re-established to this day. The poverty of modern farm workers is stark and unacceptable, especially considering the enormous profits of food companies.

Unfortunately I don’t think the UFW saga is so exceptional. For sure, the charismatic Cesar Chavez and his well-publicized use of nonviolent fasting and marching, and the remarkably successful consumer grape boycott (never matched before or since), give this story its inspiring specificity. Similarly, some of the darker aspects, like the role of Synanon, are quite specific to Chavez. But the logic of a top-down union, its lack of transparency or rank-and-file democracy, its general caution and obstructionism when workers began to act for themselves, are all characteristic of the mainstream of U.S. trade unionism going back to the beginnings.

Now I’ve voted for the SEIU! I held my nose while I did it. The local officials I met promise they are different, that they are working for a decentralized, horizontalist, transparent, and friendly to worker autonomy type of social unionism, rather than the familiar disaster implied by its parent International. I am pretty sure, assuming the union vote wins, we’ll have a couple of years in which to try something different, to see if we can organize to really alter our conditions of employment, the conditions of pedagogy at the Art Institute, and more ambitiously, to take on the ridiculous rise of the radically overpriced–and often worthless–Debt-Plus-Precarious Professor degree factory that is increasingly the model across higher education. I am unfortunately pretty sure that if we can find a way to address the deeper (il)logic of how higher education works, the SEIU International will come in and put Local 1021 into Trusteeship and force the organization to back to being a “normal union.” Only time will tell. It would be sweet to look back in a few years and realize that we were in on the beginning of something much bigger than we could imagine when it began.

Turns out this was a dead-end on our ride, and we had to go back, but it was a sweet golden light moment with a great view of the refinery and Mt Diablo behind it.

I could give you the nihilist push-back on this hopeism about reforming higher ed and reforming unions and making the butterflies dance again, but no one likes a buzzkill, and there is a new classic by Gabriel Thompson on the subject of farm work and poultry workers that would give this reportage a contemporary twist.

So I read books, yeah, and I can one-up anybody on any subject they choose to bring up. Who cares – am I running for running for rationalist troll of the year? Why keep raising these snotty rejoinders? Well, because your essayage is always precise and fresh, unlike this even more outre older dude hopeism from Counterpunch: http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/05/16/how-did-we-get-here-university-hall-at-this-point-of-time-the-anthropocene/.

Great reading, as always. I read it on an Amtrack train speeding through the beautiful Delta and flatlands of Stockton and Modesto. Perfect place to read this.