Spent the bulk of the long weekend at a bucolic bit of land west of the Mendocino town of Willits. The denizens call it “Witness Peak” and there is a spectacular small volcanic peak right in its midsts, along with a variety of rolling poison-oak covered hills, beautiful buildings built over the past decades, and a pile of good friends. Getting there is a bit of an ordeal, a 3.5 hour drive at full speed, rather longer with friends who like to stop a lot and take a more meandering pace.

One of our pauses came in the misnamed “Old Downtown” of the new ex-urb of Windsor. I knew Windsor back in the 1970s when I went to Sonoma State and lived for a while in Forestville, working at the Books Inc. in Coddingtown in Santa Rosa. Loretta, my then-manager, had a place in Windsor, and I don’t recall there being anything like a center or a real town… just a crossroads with a gas station and a minimart, surrounded by an indeterminate number of ranch houses and farms.

Now Windsor’s “Old Downtown” is like Disney’s Celebration in Florida, a few dense blocks of fake old buildings full of condos and chainstores, faux antique lamp posts and an immaculate, orderly, antiseptic anti-hominess that must reassure someone that the chaos and uncertainty of urban life have been permanently barred from entry. It seems that WhiteLand is the overriding goal of such exurbs, even when a smattering of upscale BUPpies and Asian professionals sometimes give ethnic cover to the larger social agenda of segregation. We couldn’t help but wonder, as we clutched our gourmet caffeinated beverages and sped out of there as fast as we could, what will the first political demonstration there look like? When will it happen? What will it be about? Most of the answers I can quickly conjure up aren’t very inspiring…

I so rarely go to the exurbs, let alone the suburbs (which are decaying as I write, soon to be the new slums of the 21st century, as the frightened keep moving further out and the bored move back in to the urban core). Passing through a place like Windsor reminds me about my separation from what passes as ‘normal’ America, confronting me with my own version of “Otherizing.”

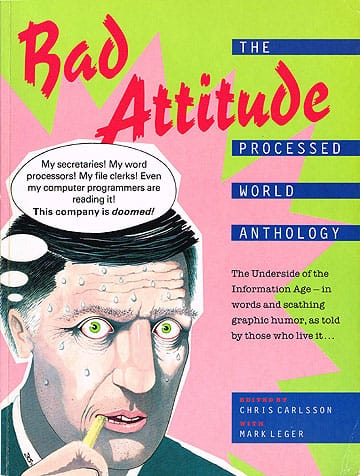

A brief pause for a word from our sponsor for today’s Blog entry:

from the back cover of Processed World 30, back in 1993, “Community Otherizer”.

It reads: “Politicians! Civic Leaders! Aspiring Spokespeople! You want to move people… GET THEM BEHIND YOU! You need the all-purpose scapegoat maker: COMMUNITY OTHERIZER. Just sprinkle liberally over stereotpyed representations of ethnic and lifestyle subcultures, and before you know it you’ll be RIDING THE WAVE! Once you’ve successfully Otherized, you’ll need our followup treatment ETHNIC CLEANSER Our bulging warehouses in Serbia, Palestine, Uganda, and Azerbaijan are standing by: Call 1-800-SPARKLE (Free personal facial scrubber with each order).

And now back to our irregularly scheduled blogging…

Hugh D’andrade did a great job of addressing this larger chasm between ‘us’ and ‘them’ in his article in The Political Edge called “Interrupting the Monologue”. Going from the Mission District to any exurb is to immediately face this; to properly digest it is to at least pause long enough to notice that the rhetoric of radical change is not obvious nor particularly resonant in such a place. Which might make us stop and think about how our ideas connect to people who are making quite different choices, usually motivated by substantially different ideas of what being alive feels like, what the range of dangers and challenges is that we face as humans, and so on.

With alarming frequency, people attracted to radical change aren’t really interesting in finding out what people think and do, but merely who they are. And judging all these human books by their covers, we make up our (often smug) minds about the relative stupidity or venality of these others. I know that the preponderant reality of such judgementalness and racism in the United States is that semi-automatic fear and intolerance that greets people of color when they venture into the ever-larger segregated regions. Nevertheless, I am deeply frustrated and offended by the corresponding racism that is being reinforced unconsciously by a fair number of activists engaged in promoting an agenda of ‘confronting white supremacy’ in ALL spheres of life.

This is a big topic, and one that deserves careful thought and argument. So I won’t claim to make my whole argument in this blog entry, and I don’t expect anyone on any side of this ongoing cultural discussion to have the last word. But the symmetry between a blindly racist culture and an obsessive and judgemental subculture of opposition is striking. The framing of the discussion with terms such as ‘privilege’ is particularly disheartening if we take seriously the notion that revolutionary change depends on the active participation of the majority of society. If the starting point to be accepted as politically relevant and involved is to publicly renounce your supposed ‘privileges’ (as opposed to, say, being a resolute opponent of institutional bigotry, social exploitation, toxic poisoning of whole communities, etc.) isn’t it obvious that an awful lot of people aren’t going to join in (unless they have a personality that is comfortable with cult-like self-renunciation)?

It belies a certain psychological immaturity to frame radicalization this way. All white people are not privileged because they’re white! If they are treated with respect by police when stopped that is not a privilege (though it is clearly a surprise!), but it is a right being denied others who are not treated the same. If they can walk in to a business and be treated courteously (so they’ll spend money there in the crucial cycle of exploitation that commodity society depends on), that is not a privilege, but it is a right being denied others who are not treated the same. “Access” is not available to everyone, whether it’s access to college, to a TV or radio talk show, the basic goods of consumer society, or even just food and shelter. Inequality of access is a symptom of a hierarchical society that produces nothing as well as it produces divisions and separations.

Affirmative action programs claim to ameliorate the problem of access. But these programs were created to halt the civil rights demands that were pushing into every sphere of life, demanding a real egalitarianism, one which threatened to up-end the logic of capitalist society. Affirmative action promised equal access, but really served to limit political and social demands in a way to reinforce the underlying (false) logic of meritocracy, of personal responsibility for success. The counterattack on quotas and set-asides was a completely predictable outcome of accepting the logic of this tepid reform in place of a more thorough-going restructuring of society.

Anyway, this topic is long and tangled. I wanted to use this entry to broaden the topic a bit from the usual black-and-white focus that it assumes so easily. I finished two books this weekend that did a bit of helpful juijitsu on my own frames of reference. First, Donna Haraway’s pocket-sized “Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness” (Prickly Paradigm Press: Chicago, 2003), and second, Mike Davis’s “Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the U.S. Big City”(Verso, 2000). I hope no one will take offense that a thread of this discussion is about to be the relationship between humans and dogs. It is not an analogue or a substitute for the problematic relations between white and black America. But it is a way of sidestepping our own predictable and somewhat automatic thoughts and responses, turning our attention to a different kind of relationship that doesn’t usually get an historical or political look, and at least in my case, is a good place to examine fixed ideas.

Davis’s book about Latino inmigration and urban transformation is an important update to our sense of who lives in the cities and what are the real dynamics of populations, municipal governance, entitlements, competition and cooperation. Though Davis is direct in his call for a black-Latino alliance, one that works through rank-and-file trade unionism, his book also uncovers some of the more difficult problems facing these two large communities as they confront the inequalities and injustice of the larger society but find themselves increasingly pitted against one another in a zero-sum (non)game of urban survival. (I’m not going to review his book further than that, but I do recommend it as an important corrective to the rear-view mirror urban politics that still predominates in the U.S.)

Haraway’s manifesto confronts my own deeply held prejudice against dogs. I have been allergic all my life, which might have to do with the fact that I was bitten in the face at age 3 by an aging and grumpy dog that was about the same height as me, but I have grown to resent the infantilization of pets in general and dogs in particular (that I’ve witnessed all too many times). I can respect someone loving their dog and having an intense relationship with it, but I just hate the mislogic of treating a dog like a child, or presuming it has a ‘right’ to be brought in to any space open to the public, as though it were a human with equal rights. Haraway probably agrees with me about that, and her ornery, thoughtful independence is why I really enjoyed her manifesto. She doesn’t cater to the American pet owner at all, but tries to take a much deeper and longer look at the historically specific relationships between dogs and humans over the long haul.

The paradigmatic story has it that

“Man took the (free) wolf and made the (servant) dog and so made civilization possible. Mongrelized Hegel and Freud in the kennel? Let the dog stand for all domestic plant and animal species, subjected to human intent in stories of escalating progress or destruction, according to taste. Deep ecologists love to believe these stories in order to hate them in the name of Wilderness before the Fall into Culture, just as humanists believe them in order to fend off biological encroachments on culture.

“These conventional accounts have been thoroughly reworked in recent years… I like these metaplasmic, remodeled versions that give dogs (and other species) the first moves in domestication and then choreograph an unending dance of distributed and heterogenous agencies… I think the newer stories have a better chance of being true, and they certainly have a better chance of teaching us to pay attention to significant otherness as something other than a reflection of one’s intentions.”

Haraway’s book ranges across many philosophical points. In contemplating ‘significant otherness’ she comes down solidly in favor of specificity and against broad generalizations, a basic approach that I would like to promote for discussions of racism, too. Haraway, in her pursuit of understanding her own relationship to her dogs, jumps into the cyberworld of dog trainers and lovers and finds some smart people who help shape her argument. And it’s Haraway’s easy move from the specifics of her topic to the gnarlier areas where these ideas pop up by themselves that makes the Companion Species Manifesto so useful. Vicki Hearne, a famous companion animal trainer and language philosopher (died 2001), gives Haraway an opening to go deeper.

“Communication across irreducible difference is what matters [among companion species]. Situated partial connection is what matters; the resultant dogs and humans emerge together in that game of cat’s cradle. Respect is the name of the game… Just who is at home [in the animals trainers work with] must permanently be in question. The recognition that one cannot know the other or the self, but must ask in respect for all of time who and what are emerging in relationship, is the key. That is so for all true lovers, of whatever species… I believe that all ethical relating, within or between species, is knit from the silk-strong thread of ongoing alertness to otherness-in-relation. We are not one, and being depends on getting on together… [Hearne’s] resistance to literalist anthropomorphism and her commitment to signficant otherness-in-connection fuels her arguments against animal rights discourse… She is against the abstract scales of comparison of mental functions or consciousness that rank organisms in a modernist great chain of being and assign privileges or guardianship accordingly. She is after specifity.”The outrageous equating of the killing of the Jews in Nazi Germany, the Holocaust, with the butchers of the animal-industrial complex… or the equating of the practices of human slavery with the domestication of animals make no sense in Hearne’s framework. Atrocities, as well as precious achievements, deserve their own potent languages and ethical responses, including the assignment of priority in practice. Situated emergence of more livable worlds depends on that differentiated sensibility.”

This passage does a nice job of confronting indirectly the philosophical retardedness that plagues so many people attracted to a political practice that consists mostly of veganism or guilt-tripping people over consumption. The easy application of complex historical narratives to the issue of the day (much like people bandying about the term ‘fascism’, though it is clearly more applicable than it was 20-30 years ago) makes the speaker sound uninformed, if not stupid. Historical amnesia and a cultural antipathy to any but romantic and nostalgic ideas of the past cripple us every day. Haraway’s eloquent plea for historical specificity in relations between species is one part of her analysis that I DO think applies much more broadly. And she can only make that argument because she’s spent so much time excavating real histories, examining the loaded ways language and philosophy shape inquiries, but coming out the other side firmly in favor of rigorous and uncompromising investigation, paying attention, giving respect, and learning to learn.

Here’s a last quote from Haraway to whet your appetite for more of this intellectually very fun and stimulating pamphlet:

“The introduction, from blasted peasant-shepherd economies, of Basque Pyrenean mountain dogs, who were nurtured in the purebred dog fancy, onto the ranches of the US west to protect Anglo ranchers’ xenobiological cattle and sheep on the grasslands habitat (where few native grasses survive) of buffalo once hunted by Plains Indians riding Spanish horses” along with the study of contemporary reservation Navajo sheep-herding cultures deriving from Spanish conquest and missionization” ought to offer enough historical irony for any companion species manifesto. But there is more. Two efforts to bring back extirpated predator species rehabilitated from the status of vermin to natural wildlife and tourist attraction, one in the Pyrenean mountains and one in the national parks of the American west, will lead us further into the web.”

And further she goes. By the end, I could almost imagine having a relationship with an animal again (I grew up with 3 cats and always feel a psychic affinity with cats when I meet them, which they usually reciprocate in allergy-inducing ways!). But I’ll leave it to Haraway to stimulate your own desires:

“When I stroke my landmate’s sensuous Great Pyrenees, Willem, I also touch relocated Canadian gray wolves, upscale Slovakian bears, and international restoration ecology, as well as dog shows and multinational pastoral economies. Along with the whole dog, we need the whole legacy, which is, afer all, what makes the whole companion species possible… Inhabiting that legacy without the pose of innocence, we might hope for the creative grace of play.”

Leave a Reply