I spent Thanksgiving with a pleasantly boisterous and squishily affectionate gaggle of about 75 friends at an obscure box canyon resort called Saratoga Springs (not far from Ukiah or Clear Lake). It’s an annual event going on a decade now, and many of the friendships discovered there have been extended to our daily lives in the Bay Area, an ever-expanding community that feels a lot like an extended family.

Many of the participants understandably object to the whole amnesiac and gluttonous ritual known as ‘Thanksgiving,’ which has led us in each of the last two years to begin with a large group discussion. The “dark side” of Thanksgiving was aired out two years ago and this year the focus moved more broadly to questions of justice and our individual experiences of oppression. In both discussions an interesting dilemma emerged–when and how do our current choices and behaviors derive meaning from the past? In other words, does Thanksgiving have to carry the weight of genocide past, or can we collectively redefine it today as a convivial gathering and a brief long weekend of community and engagement?

Beneath this practical issue lurks ever-present concerns about noticing, responsibility, memory and history. Simply put, how can any of us ever enjoy a good meal with friends without simultaneously admitting that our prosperous and peaceful moment depends not only on centuries of genocide and slavery, but actually perpetuates real terror and barbarism right now, while we’re eating! We make political and practical choices all day long every day to ignore or at least skip over a very heavy history of violence and inhumanity that contributed crucially to our “peaceful” existence. How do we do that? Is it just a question of moral failure? I think not. There are intricate institutional and psychological mechanisms that have shaped our culture of irresponsibility, atomization and individualism.

Again I find my reading overlapping in surprising ways. Three books I’ve been reading in the past couple of weeks offer some insight into the aforementioned mechanisms (Gangs of America: The Rise of Corporate Power and the Disabling of Democracy by Ted Nace; Disciplined Minds: A Critical Look at Salaried Professionals and the Soul-Battering System That Shapes Their Lives by Jeff Schmidt; On the History of Natural Destruction by W.G. Sebald). Gangs of America is a highly readable account of the emergence of corporations as we know them today: unaccountable, immortal, anti-social. Nace provides an important missing history: the clear anti-corporate biases of the U.S. founders and the population right into the latter 19th century. Corporations were mistrusted and in general only allowed to exist (by government charter) for specific purposes and limited times. Nace wants to find out how that healthy social control was eroded, ultimately leading to the 21st century reality of nearly untrammeled corporate power.

He details the individuals who slowly but surely created a whole new legal framework for corporations–dozens of Supreme Court decisions (and some non-decisions) have unleashed a malignant institution which has systematically subverted democratic norms and all efforts to subordinate corporations to meaningful social controls. An upside-down legal world has extended rights meant for individuals to legal fictions called corporations, ostensibly because individual shareholders’ rights are equivalent. But it is the limited liability corporation that precisely makes no humans responsible for its behavior. Shareholders are screened from decision-making and consequences; managers make decisions but are utterly constrained by their fiduciary responsibility only to pursue profits regardless of social or moral or environmental effects; workers do what they’re told or lose their jobs; customers “choose” from a series of end products with no say over how or why they came to be.

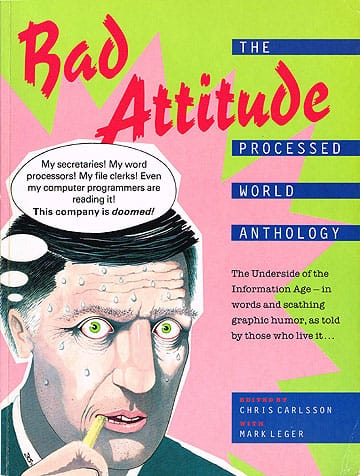

Jeff Schmidt’s Disciplined Minds delves into the ongoing mystery of why skilled, well-rewarded technical and professional workers blithely go along with anti-social and dehumanizing corporate behaviors and goals. More than anything Schmidt excavates the attitudinal expectations that undergird the selection processes that in turn allow entry to aspiring professionals.

“The qualifying attitude, I find, is an uncritical, subordinate one, which allows professionals to take their ideological lead from their employers and appropriately fine-tune the outlook that they bring to their work. The resulting professional is an obedient thinker, an intellectual property who employers can trust to experiment, theorize, innovate and create safely within the confines of an assigned ideology. The political and intellectual timidity of today’s most highly educated employees is no accident.”

As a trained physicist himself, Schmidt was fired from his job at Physics Today when this book appeared, ostensibly because he admits in the introduction that he “stole” time on the job to write the book. He dissects the processes by which people are chosen–and choose themselves by attitude and behavioral adjustments–to become professionals, whether physicists, doctors, lawyers, or any other profession. For aspiring scientists in particular, Schmidt’s analysis illuminates the false neutrality of supposedly pure technical and empirical knowledge, brilliantly presented in a chapter called “The Concealment Game.” The federal government funds about 75% of all physics research, and a huge proportion of that goes for military and weapons purposes. Officially the requested research is for condensed matter physics, plasma physics and particle physics, and with that financial incentive an overwhelming majority of the degrees granted are in one of these subfields.

You should read the book to see the specific, detailed examples, but Schmidt shows convincingly how curiosity gets “adjusted” to suit the needs of funders, that often turn out to be weapons procurers. In the process of progressing through a professional training in science, the student’s original excitement and hope to contribute to social well-being gets channeled into seemingingly abstract “pure” research goals, but whose application is ultimately anti-social. As the training progresses, many students drop out or are expelled, winnowing the crop to those most adapted to the directed curiosity of the funders, those least likely to continue insisting on an independently determined course of research.

From this process, vastly oversimplified here, come the nightmares of reason Francisco Goya lambasted during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain before the Industrial Revolution. But today’s nightmares more often fall from the sky instead of being imposed by bayonet (not that death and rape squads, torture and murder, aren’t still erupting every day from the dark recesses of human depravity). And that’s where my third book comes in, Sebald’s On the Natural History of Destruction. In it he describes the horrific destruction of German cities by mass incendiary bombings in WWII. Over 600,000 civilians were killed, often in hellish firestorms by this strategic bombing.

An interesting side note for “fans” of air war–the German war machine was never seriously damaged by these attacks, just as the air war in Vietnam was effective at terrorizing and killing civilias but not in destroying military targets. Now, as Sy Hersh notes in his latest New Yorker piece, the Cheneyites are planning to increase the already unaccountable bombardment of Iraq from the air while removing exhausted and demoralized ground troops in response to the political pressure of the ’06 midterm elections.

Air war IS terrorism–of the greatest magnitude, unimaginable if you’ve never lived through it (I haven’t). No state in the world today is as capable of pure unadulterated terrorism as the United States. W.G. Sebald was one of the first to seriously investigate how Germans managed to suppress their own experiences of terror from the sky, apparently blotting out a whole range of visceral and horrifying events. After WWII German writers could barely acknowledge what had happened, and when they did it was often in the most banal and even self-romanticizing ways.

The sheer barbarism of the mass destruction could not be lived with by the generals ordering it (military necessity was the rationale with no evidence that it was effective), by the airmen doing it, and it turns out, by the civilians enduring it. A jarring process of disconnection, forgotten as quickly as it happens, is the crucial piece.

Isn’t that normal? Don’t we all do a version of this every day? How can we maintain any sense of normalcy while Iraq is being blasted and pounded, Iraqis are being tortured and murdered, all in our name? (Not to mention the murders and torture sponsored by U.S. taxpayers in Haiti, Colombia, Afghanistan, Egypt, Israel/Palestine, et al.) But what is normal? Taking these three books together, a global society has been constructed that normalizes mass murder, even making of it a necessity. But the institutions that are most responsible for driving the process are virtually unaccountable to any political or social or human authority. Increasingly military action is being placed beyond scrutiny as well. And even if there are occasional glimmers where an individual might alter the course of these lumbering barbaric behemoths, such individuals have been pre-selected by a “soul-battering system” to be exactly incapable of exercising independent critical thought and behavior that challenges the logic of corporate power and the militarization of everyday life or the basic objectification of all life into commodities and resources to be devoured by a planetary work machine.

So our challenges are huge and our odds of success are rather small. Nevertheless, this system is ALSO remarkably fragile. Fissures and cracks abound. You could even optimistically claim that this kind of blogospheric discourse is one way we are exploiting that cracked fragility.

Or maybe I’m just talking to myself!

Fair enough. That was a bit of a glib ending. Not sure if these comments will solve that problem, since my perceptions, in the absence of actual action, can be seen as wishful thinking. Nevertheless, I think there are enormous reservoirs of discontent that don’t get much notice. My sense of this period is that there are big changes percolating beneath the surface, but are still some distance from making themselves felt. That is, the mass media won’t pay any attention until there are riots in the streets or mass strikes halting the economy.

The fragility of the system stares us in the face every day. Daily life depends on cooperation and there are countless times every day when people might withhold cooperation from overtly dehumanizing moments. The increasing distance between verifiable truth and the blatant falsehoods that pass as reality are remarkable. The only thing that really solidifies the status quo is the fear of falling, the fear of change, which is reinforced by an abysmal lack of public imagining, or discussion and expression about other ways of living. And yet, many people are engaged in daily acts of mutual aid, cooperation, ecological restoration, community building, etc., all of which have the potential to create the foundations for a different society (of course most of them can also be coopted into the endless orbit of business, nonprofit or otherwise)…

What will tip us from cooperating with our own immiseration and degradation over to making a world worth living in? Hell, if I knew that…

Do you think you could comment a little bit about this fragility? As great as your exposition was, I wanted to hear just as much as to why you think this behemoth of a system is yet so fragile to those who would take it down.