San Francisco is nearly at full boil. Rampant eviction and displacement, combined with a nearly unprecedented frenzy of new construction, and a wild west of new restaurants, boutiques, and other establishments opening and closing like a spinning top, is changing the face of the city so rapidly that it’s becoming unrecognizable even to those of us who have lived here for decades. Hardly a day passes without news of another friend losing their home to a new buyer who is determined to evict either using “owner move-in” or the state “Ellis Act” which allows owners to leave the rental business and clear their buildings.

Curiously, thousands of apartments are estimated to be lying empty in San Francisco, held as investments by distant speculators. Thousands more lay unused by the elite who maintain empty apartments in so-called “global cities” spanning the world, pied-a-terre’s for the 1% who drop in once and a while for fun or business. Many more homes have been informally converted into temporary tourist dwellings via the latest dotcom scourge AirBnB, and similar predatory neoliberal business models masquerading as “the sharing economy.”

San Francisco progressives, once known as the Left, but today a bit too compromised and confused to earn consistently even that tepid moniker, are a paper tiger, unable to contest or even slow down the onslaught ripping the fabric of the city. The long-term demise of organized labor, holding on for dear life among city workers, transit workers, and some hotels and the building trades, is an important part of the shrinking of social opposition, but it goes a lot further than that. In the first dotcom boom-and-bust in 1999-2000 a spirited movement emerged, centered in the Mission District and with activist pressure showing up in most parts of town, but an equivalent effort at contestation has simply not appeared this time around. Protests echoing the decade-ago efforts have not drawn the numbers or the attention in 2013; the fact that gentrification has proceeded stealthily and steadily all these years has already radically altered the demographics of the city. Thousands of wealthy people are now living in new condominiums in the South of Market, downtown, Mission Bay, the Haight-Ashbury, the Fillmore, and the Mission District. Thousands of old Victorians have been bought and removed from the rental market, now owned by the burgeoning population of well-paid lawyers, financial analysts, medical and biotech workers, and of course the much-blamed tech workers of the social media empires.

Trying to make sense of the trajectory from the much-heralded Left Coast City of the past to the increasingly brutal neoliberal cauldron of today is difficult, but two new books published this year offer complementary analyses that help start the introspection. Karl Beitel’s Local Protest, Global Movements: Capital, Community, and State in San Francisco (Temple University Press, Philadephia: 2013) and Jason Henderson’s Street Fight: The Politics of Mobility in San Francisco (Univ of Massachusetts Press, Boston: 2013) both set out to analyze the state of progressive politics, albeit from different points of focus (I should say that I consider each of these authors my friend, too).

Trying to make sense of the trajectory from the much-heralded Left Coast City of the past to the increasingly brutal neoliberal cauldron of today is difficult, but two new books published this year offer complementary analyses that help start the introspection. Karl Beitel’s Local Protest, Global Movements: Capital, Community, and State in San Francisco (Temple University Press, Philadephia: 2013) and Jason Henderson’s Street Fight: The Politics of Mobility in San Francisco (Univ of Massachusetts Press, Boston: 2013) both set out to analyze the state of progressive politics, albeit from different points of focus (I should say that I consider each of these authors my friend, too).  Beitel hails from a more traditionally left perspective, and he’s trying to reconcile the history of mass movements and political parties with an eco-Marxist perspective in his focus on housing politics in San Francisco from the 1970s to the mid-2000s. Henderson is a critical geographer teaching at SF State and his book focuses in on the transportation realm, identifying three ideological poles (conservative, neoliberal, and progressive) that have confronted and compromised with each other to create the stalemate we face daily, leaving everyone dissatisfied whether motorist, bus rider, bicyclist, or pedestrian.

Beitel hails from a more traditionally left perspective, and he’s trying to reconcile the history of mass movements and political parties with an eco-Marxist perspective in his focus on housing politics in San Francisco from the 1970s to the mid-2000s. Henderson is a critical geographer teaching at SF State and his book focuses in on the transportation realm, identifying three ideological poles (conservative, neoliberal, and progressive) that have confronted and compromised with each other to create the stalemate we face daily, leaving everyone dissatisfied whether motorist, bus rider, bicyclist, or pedestrian.

Both of these slim volumes provide great histories: Beitel highlights the early history of resistance to redevelopment and highrises and how that led to the inadequate-but-better-than-nothing rent control that passed in 1979 (and we still have now, strengthened in subsequent years by savvy ballot-box efforts led by the SF Tenants Union). In a later chapter he recounts the rise of the Mission Anti-displacement Coalition (MAC) and its relationship to the Willie Brown era of unrestrained for-profit building during the first dot-com boom (which really is still ongoing, we now know). Henderson usefully tells the story of the original Freeway Revolt in the 1950s-60s and shows how the coalition that stopped the road builders then was as much conservative as progressive. In a later chapter he gives a great history of the 2nd Freeway Revolt of the 1990s that took place in the wake of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and the opportunity it presented to tear down the Embarcadero and Central freeways. He shows how progressive activists came to accept neoliberal arguments about profitable real estate opportunities as a way to forge an alliance against the conservatives who insisted the city government bolster and expand automobility by repairing the damaged freeways.

These two books, which often parallel each other in interesting ways, also demonstrate one of the problems they’re describing: the isolation of local-issue campaigns from one another. They also both demonstrate the problem of academic theses, that the focus must always be narrowed to an acceptable topic at the expense of a more comprehensive and complex approach. The book market in general is in trouble, and broad analytical works are growing harder to find. Publishers, even academic ones, seem to prefer the easily categorized topical treatments—in this way political writings mirror the separations that political movements keep reproducing, at least in the U.S.

Beitel looks in depth at housing politics and does situate it in the broader context of urban movements:

…urban movements’ often seemingly disparate struggles… articulate a particular systemic contradiction that is internal to the nature of capital accumulation. This suggests a theoretical link between struggles over urban land use, transportation, and housing and movements that focus on impairment and destruction of the natural environment via processes such as global warming, loss of natural habitat, and resource depletion. It also establishes a theoretical basis to rethink “the urban” in relation to energy consumption and waste generation. Urban movements can thus be seen as a particular “species” of the larger “genus” of social movements that emerge in response to capital’s tendency to degrade or underproduce the conditions of production. (Beitel, p. 53)

But the large part of his book documents and analyzes the housing movement and land-use and zoning debates in isolation from other efforts to address the urban environment, such as ecology, energy, or transportation. Suggesting this connection at the outset of his book and in its title, I hoped he would follow through and do a more thorough job of juxtaposing the housing and land-use struggles he covers so well to the parallel stories of other locally based urban movements.

Henderson does something similar in his book, touching on much broader context, but not really integrating parallel experiences and arguments with his sharp look at transit/mobility politics. He brings in the bigger picture almost two-thirds into his book, explaining the very helpful concept of revanchism:

Revanchism is the recovery of lost territory or status. Used in critical geography, the term refers to the neoliberal and conservative undoing of the redistributive social policies established in the New Deal and through the 1960s. In this sense revanchism means a return to the original liberalism of nineteenth-century capitalism unfettered by regulation and progressive policies and enabling markets to dominate the organization and allocation of urban space. With respect to livability, revanchism includes the strategies of disciplining certain aspects of the city, making the city “safe” for gentrification through such policies as removing the homeless and displacing social services. Revanchism includes the defunding of affordable public housing and education and the disciplining of public sector workers, while offering tax incentives to corporations, privatizing education, and subsidizing (with public funds) upscale housing and urban amenities through redevelopment schemes. (Henderson, p. 160)

Here we have a framework to understand the underlying logic of a lot of the politics of our era. The term ‘neoliberalism’ confuses many Americans who think ‘liberal’ means something vaguely left-wing (a confusion mightily helped by the right-wing echo chamber which dominates television and radio), but Henderson here usefully reconnects it to its 19th century origins. This in turn helps us understand how muddled the discourse of progressivism is in our time, since many self-proclaimed progressives limit their politics to liberalism, thus supporting market-based solutions as the limit of social organizational possibilities. The long legacy of anti-communism in the U.S. still dominates many people even those on the soft Left. The present-day results of this anti-communist legacy, combined with 40 years of neoliberal assault on the public sphere in favor of private capital leaves most people’s imaginations trapped in a very narrow set of possibilities when it comes to political choices.

The quasi-progressive embrace of “livability” and “new urbanism” arguments also serves to mask the brutal social consequences of these essentially neoliberal approaches. It is not surprising that progressives still committed to equity and redistributive justice remain suspicious and often hostile to efforts to implant parklets, bike lanes, and other visible elements of a more livable city.

Many populist-leaning progressives look upon the livability agenda as suspect because it is perceived to be a leading contributor to gentrification and displacement. As more affluent people seek out urban living near good transit, the areas that are primed for livability increase in market value. Evictions and rent escalation then push the working poor (and, in San Francisco, the middle class) out of the region’s most transit-accessible, walkable, bikeable neighborhoods. To overcome that tension progressives demand government intervention in the real estate market, such as rent control and inclusionary housing laws, but by all accounts these policies are not stemming the tide of displacement in San Francisco. (Henderson, p. 23)

Parklet on Haight Street… the Valencia corridor probably has more than any other single area of San Francisco.

In the Mission District, ground zero for the current tsunami of displacement and ethnic cleansing from San Francisco, local Latino businesses along the endangered 24th Street corridor have come out strongly against parklets, the replacement of one or two parking spaces by public “corrals” made of wood with places for people to sit and talk (by definition each parklet is a public space, not owned by the restaurant or café which often sponsor them, even though those businesses do like to create the impression that the parklet is only for their paying customers). They argue that parklets are for the gentrifying white population, and that their customer base, having been displaced to Daly City or San Mateo, requires parking for when they drive in to the neighborhood to buy their specialty foods or patronize their old favorite establishments. (The obvious truth that one or two parking spaces—especially on a busy commercial corridor—are not relevant to the overall squeeze on parking in a neighborhood where more money is moving in, hence more people with their own cars, hence less parking in general!) Nevertheless I have heard people who cloak themselves in social justice rhetoric defending an automobile-centric urban design on the grounds that it is in the best interest of working people! In supporting the passionate commitment to personal automobiles still favored by many working people (at least those still large numbers who own a car), social justice activists may not realize they are embracing a deeply conservative ideology in which automobility is naturalized and essentialized.

…possessive individualism through automobility translates into a lack of civic and social responsibility toward public space and notions of community. The transit system and the streets are perceived to be unsafe precisely because there is too much traffic. In San Francisco, the broader contemporary American political rhetoric concerning personal responsibility toward one’s family can translate into a lack of interest in collectively solving large-scale problems such as congestion, pollution, and the inequality that stems from automobility. Instead, it is supposedly responsible to move the family through the city by car—that is, to secede—and fill one’s daily needs atomistically. Meanwhile, automobility enables one to circumvent, if not secede from, the perceived evils of the city, one of which is homelessness. (Henderson, p. 105)

Progressives and neoliberals found common ground on parking limitations in new developments and in expanding bicycle space in the city:

While neoliberal developers may have liked the requirement for residential parking in new high-rise condominiums, a blanket approach that imposed more government regulation was threatening ideologically as well as financially. (Henderson, p. 108) Incorporating the themes of livability, California’s SB 375, the Sustainable Communities and Climate Protection Act, explicitly calls for reducing Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) by redirecting residential growth to compact urban centers, places like the Market and Octavia area in San Francisco and in the areas around BART stations in the suburbs… Progressives envision SB 375 as achieving spatial planning goals that address climate change and the environment, while neoliberals envision the bill as a streamlining of the production of highly profitable infill development.(Henderson, p. 124, emphasis added)

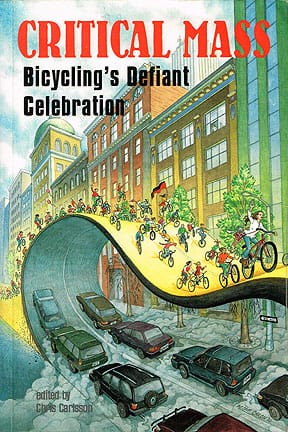

I helped launch Critical Mass 21 years ago, and have often spoken out in favor of bicycling because of an implicit—or at least potential—radicalism embodied in the choice to cycle. But I’ve been dismayed at the steady drift rightward of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition all these years, the mainstream group that once felt like natural allies and now seem like an alien force bent on draining bicycling of any utopian or visionary depth. Henderson suffers no illusions about the growing alliance between cyclists organized into the Bicycle Coalition and the neoliberal gentrifiers ravaging so many neighborhoods.

…Bicycling has also come to be seen as a key part of economic development in neoliberal, entrepreneurial discourses. In sum, a successful city is one that has a youthful, fit, creative class that bicycles. This neoliberal discourse about bicycling has influenced the politics of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition… This progressive-neoliberal rapprochement around bicycling was mutually beneficial in that progressives were realizing possibilities of comprehensive bicycle space, while neoliberals were recognizing that bicycling, as part of the broader livability agenda, was a profitable economic development strategy. (Henderson, p. 133-35)

The Sangiacomo Trinity Plaza project, hundreds of new market-rate apartments on 8th between Market and Mission.

The foundation going in at 15th and South Van Ness for a 5-story condo project… note the funny mural that is being covered up by the construction…

Hundreds of new apartments are being built in San Francisco as I write, many of them in new highrise towers along Market Street. An impending fight over 8 Washington Street, a condominium project slated to be built on the Embarcadero just north of the Ferry Building, will be on the ballot this November. If built, 8 Washington would create several dozen multimillion dollar condos and exceed the established height limits adjacent to the city’s waterfront, putting a “wall on the waterfront” as opponents have tagged it. This project was already approved by the city’s planning establishment and Board of Supervisors, gaining a super majority including some of the more progressive-minded Supervisors. Their support was gained by the developer promising to make a $25 million contribution to the affordable housing fund, a substantial amount in a time of fiscal austerity and budget crisis. A citizen effort has managed to stop the project and put it to a vote this coming November and now both sides are out campaigning—the millionaires behind the project are engaged in an Orwellian disinformation campaign under the slogan “Open the Waterfront”!!

The 8 Washington project gained progressive support because of the domination of neoliberal thinking in this era:

Affordable housing development has become increasingly contingent on local government underwriting the profitability of private market-rate housing and commercial office development. Because the promise of greater future tax revenue increments constitutes a major source of affordable housing development, nonprofits have found it expedient to buy into the overall framework of the public-private partnership development model… The effect is to confine conflict within the parameters first and foremost beholden to underwriting the rate of return demanded by private developers. This reinforces the corporatization of low-income housing development and the logic of accommodation to the seemingly impervious realities of the private market. (Beitel, p. 93)

On this logic, both Beitel and Henderson see things similarly, but Beitel also sees the political leverage opened by the desirability of meeting the market demand of the new strata:

Developers and realtors in San Francisco recognize that there is a reurbanizing class stratum interested in the consumption of livability. San Francisco attracts and incubates a new bourgeoisie and a petit bourgeoisie or creative class, including executives and management, self-employed consultants, engineers, and especially tech workers in biotech, software, and Internet social networking firms. (Henderson, p. 100)

Cities that are highly desirable investment sites will favor the ability of organized citizen groups and activists to bargain over community benefits, linkage fees, infrastructural provision, affordable housing, and design specifications aimed at protecting the aesthetic and functional integrity of existing neighborhoods… Neighborhood associations and community organizations thus play a critical regulative role in this vision of government, serving as the preeminent vehicles for articulating the policy preferences of local residents. (Beitel, p. 153 and 158)

Beitel does some good work unpacking the complicated way the city of San Francisco has systematized public comment and organized dissent through nonprofits at the expense of an ongoing, coherent political opposition. As we ponder the peculiarly atomized and often ineffective politics of the many organizing efforts that have appeared during the past years, Beitel and Henderson both shed important light on the way neoliberal ideology and its manifestation in public policy has disrupted and disorganized oppositional efforts.

Governmental policies of devolution and decentralization, the creation of forums of structured citizen participation, and the rhetorical emphasis on “deliberation” all constitute a framework of neoliberal implantation and, alternatively, can provide openings for urban movements to contest, and even reverse, the process of privatization and appropriation of the commons… Without denigrating the achievements of the tenant and land use movements, I would argue that San Francisco reveals the limits of this form [the local] of social action as presently constituted for building an alternative to urban neoliberalism… In the context of “actually existing neoliberalism,” theories of deliberative democracy therefore perform an ideological function of according legitimacy to existing power relations, however unwittingly. (Beitel, p. 164, 170)

Ultimately Beitel is hoping for a new kind of mass organization, which I neither believe is likely nor necessarily desirable. The kind of left politics he invokes doesn’t seem to have the people it would need to make it real.

The ambiguous nature of outcomes, and the problematic status of nonprofit organizations as vehicles of broad-based social mobilization, return us to the question of the urgent need for constructing new forms of political organization able to thread together, “crossfertilize,” and enhance the efficacy of what remains as a dispersed, heterogeneous set of constituent- and issue-based urban movements. Any serious Left reformation will need to remain grounded in the struggles of the poor and the excluded yet must find the means to reach beyond populations defined by politically and economically marginal statuses. This is a basic requirement of building any broad-based, Left-progressive political movement.

I like his final call for a deep democratization, but doubt it could make itself felt in terms of organizations we’ve known in the past. Clearly something new will emerge to confront the constraints of neoliberalism, but what form it might take is as yet unknown.

… deep democratization is fundamentally a struggle over the very form of the state itself-the demand to relocate decision-making power within agents, networks, and associations that compose the social substratum, civil society, and the microstructures of everyday life. This includes, at a minimum, the democratization of the allocation of investment and the infusion into economic life of values and norms other than the pursuit of the maximal possible rate of return on investment. Radical democratic political struggles involve challenges not only to the legitimacy of the policies of government. . . but also the very form of the state itself. (Beitel, p, 174 and 183)

Henderson, by contrast, is not seeking to spur new political organization per se. He is left offering his own prescription for a progressive agenda regarding urban mobility:

Ultimately, speed is an issue of justice, and progressives should be careful about characterizing it, as neoliberal pricing strategies do, as a commodity. Rather than enable the wealthy to pay for faster speeds through, for example, premium high-occupant toll lanes, congestion charging, and high-priced cubside parking using smart phones, all cars should be made to travel slowly in the city; further, the city should be made navigable at no greater than fifteen miles per hour, a speed deemed not only to be comfortable on calmed pedestrian streets but also to minimize injury and fatalities when there are collisions. Setting a citywide speed limit of fifteen miles per hour decreases the utility of a car, for it makes crossing town by car an exceptionally longer process. But the collective good of the city in a progressive mobility scenario takes precedence over individual desires for instant gratification and immediate access through speed. (Henderson, p. 199)

One of the newly ubiquitous sights around San Francisco is the ever-growing fleet of private luxury buses that have been established by Google, Facebook, Ebay, Yahoo, Genentech, and other employers south of the City. These private buses are their way of addressing the congestion and pollution that their employees would be creating if all of them were driving their own cars to work everyday. But instead of investing in an improved form of public transportation, open to all, what they’ve created is a highly inefficient and redundant system of privatized luxury transit, underscoring perfectly one of the main points of Henderson’s smart book:

Progressives support the environmental benefits of private commuter buses but have stood by while tech workers embrace privatized transit to the peril of public transit and a potential declining constituency for public funding. As transit is captured from low-income people who depend on it, through the proliferation of increased fares, policing, and perhaps eventually market-rate pricing and segmentation of the system, the gentrification of the city may spread to the gentrification of transit. (Henderson, p. 191)

When he was writing this a couple of years ago the new private buses were not yet so omnipresent, but in 2013, we can say that the gentrification HAS indeed spread to transit, at least that leaving San Francisco’s city limits. How long before there are two classes of Muni buses, one first class and the other for the rest of us? The re-enclosure of central cities, most dramatically in places like Manhattan and San Francisco, with its consequent expulsion of the poor and relative homogenization of class and ethnicity, is well advanced now. San Francisco, a place where experimentation, contestation, and contrarian sensibilities have always taken root and found fertile ground in which to grow, is being boiled in a vast neoliberal effort to sterilize away those epic characteristics that have shaped the city we love. Maybe we can still turn off the heat, but finding the new political forms, the leverage in our daily lives, the vision of a different way to reproduce the material world we depend on, is a tall order. I still think we can, but I know it won’t be easy or happen automatically. Many thanks to Karl Beitel and Jason Henderson for two excellent books. They have deepened our capacity to understand what’s happened before this moment, and given us some tools to help avoid falling into the traps that caught our predecessors.

I’ll wrap it up with a brief photo essay of the repaving of Folsom Street outside my house. It was fascinating to watch, and I think it’s a much more thorough job than ever done previously. They systematically rip up the asphalt down to the underlying dirt, lane by lane, replacing it with a thick layer of cement and then covering that with two layers of asphalt. It’s a bicyclist’s paradise! And in fact they’ll soon be restriping the whole length of Folsom to be only one lane auto traffic each way and a bike lane all the way. Hurray!

One has to ask; to what extent are the phenom you and the authors of the books you review describe, self inflicted? The gentrification of a city, any city where for whatever reasons more people chose to live than there is available, or excess housing stock will experience displacement. Ownership is no guarantee of stability as developers have known for millennia that everyone has their price. Sometimes the gun is literally placed at occupants heads to get them to move but here, save for the indigenous experience, it is rare. More often the entire process hinges on the choices of the occupant, who has choice, to chose to live here or there. It used to be that employment opportunities were the driver of these choices. Now, it is my observation, that “scene” has displaced opportunity and even the romantic observations of Richard Florida and other promoters, that there are clusters of persons living in enclaves of creativity, there is little evidence that they co-operate. More likely they compete; for space, for money, and attention. There are ethnic enclaves that have served as comfort zones for people who desire conformity in language, culture, or religious experience, and these enclaves have had a powerful magnetic pull on first generation refugees to the city. The history of these ghettos is that as soon as the resident population de-racinates they are off to the burbs to assimilate. They chose to leave.

The more pernicious behavior of developers and the cities that enable them is also to great extent the often unintended consequences of what “progressives” thought was “civic improvement”. The embedded language “highest and best use” has been a tool of developers since the closing of the feed lots within city boundaries. The populace signed on. And they continue to sign on. Don’t even try to test the thesis that stability is a family value at the risk of property value. The resident in place will break your heart every time as she votes to maintain her property as a source of wealth as opposed to a life support system.

And what is to be said of the coasters who would rather die than live in Detroit, where they have a chance to actually create a scene say as opposed to be on one. As the coastal cities continue to wipe out any vestige of funk, ethnicity, and trim their tall towers in pocket parks, the ultimate effect will be to provoke the exit of those to whom your piece is directed, thinking persons with some sense of place.

Or they could act out. There is little evidence that students have any stomach for civil action, even in their own self interest as I speculate they too are hedging their bets, as my gen did all those years ago, and hoping to live in the house on the hill. There are alternatives and we don’t have to look back to the French revolution for evidence. If Neal had poked around a little in Vienna he would have found evidence of residents acting out against absentee land-owners and exploiting the “squat”.

From wiki: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squatting

“However, in many cases where squatters had de facto ownership, laws have been changed to legitimize their status. Squatters often claim rights over the spaces they have squatted by virtue of occupation, rather than ownership; in this sense, squatting is similar to (and potentially a necessary condition of) adverse possession, by which a possessor of real property without title may eventually gain legal title to the real property.”

Students in Europe have been acting up/out for hundreds of years to secure affordable housing, evidence;

http://www.cafebabel.co.uk/society/article/paris-squats-in-europes-second-most-expensive-city.html

or your readers may be stimulated by the events in Christiania, in Denmark. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jun/21/deal-legalises-europe-largest-squat

But, here, underlying all of the actions and reactions, is the inescapable fact that we could chose to live somewhere else. Pulling the market out from under the exploiters of Hip-city USA, And making a life at once affordable and possibly communal.

Hi Bill,

for east coast like-minded folks, check with the people at Bluestockings bookstore in NY, and Autonomedia in Brooklyn… they should be able to put you in touch with some folks you can find resonance with…. thanks for the comments!

–cc

Hey there – you may be in a Neoliberal crockpot, but I’m out here on the east coast in NJ Gov. Chris Christie’s authoritarian suburban compound.

I love reading your work, and constantly find parallels to the “rightward shift” and mean spirited neoliberal and corporate co-optation that passes for “green” advocacy here in NJ.

Some of it is overt opportunism, whereby well endowed Foundations feed well fed entrepreneurial consulting firms that used to be called “conservationists”.

They’ve teamed up with the “sustainable development” and “new urbanism” crowds to form a toxic combination.

I work in NJ at the State level – can you suggest writers or groups in NY/NJ region that take your framework of analysis and political resistance?

I’d like to work with them – frankly, I haven’t seen anything close to the work you write about, but I am not, as they used to say, in the loop these days.

Thanks for another great post – I was glad to be introduced to the concept of neoliberal revanchism and especially appreciate the illustrations of how “progressives” have uncritically swallwed neoliberal ideas.

Hi Brian, thanks for the thoughtful comment. I just want to clarify that my highlighting those projects was in no way meant to say that whatever prior uses had been in place should have been preserved, let alone leaving empty buildings unused, but rather to show how much capital is pouring into San Francisco right now. Behind that is the myth that we can “grow” our way out of structural, systemic crises rooted in class dynamics, fear and loathing directed towards poor and disenfranchised people, and the zero-sum conflict over the shape of our streets and our transportation choices. We cannot.

A political movement that decides to engage the long-term project of rebuilding and reorganizing the city in harmony with natural systems (water, sunlight, soil, urban agriculture, etc.) would involve restructuring streets to radically reduce our dependence on private cars as the main transit choice most people make every day (still! after all we know!), expand dedicated transit and bicycling corridors, pedestrian zones, and so on. If we combine this approach with a refusal of the pointless work so many are involved in daily, we might actually create a society we can be proud of, with our shared labor and a newly invigorated public sphere. Similarly, we can’t allow public space to be only for certain types of people and not others, the apartheid-like policing of the youth of the Mission and Bayview has to end, the vast population of homeless and deranged must be housed in decent supportive buildings with food and mental health services provided, and on and on… so much to do, so many obvious solutions, so little effort actually going in the right direction. Instead, we’re making apps! How to pay for all this?!?, our fiscally responsible neoliberals will shout–there’s so much money being spent on such idiotic things, top of the list a vast military and spook empire straddling the world raining terror on people on several continents. Endless dumb work producing nothing of value, just circulating capital around and around: banking, real estate, advertising, insurance… shoddy production of basic goods that should be made to last 75 years and instead only last 7.5 months!…

sorry, had to rant. Thanks for writing!

Great post, and I’m looking forward to reading the book.

As a long-time renter in the Mission, I’m very sensitive to the dangers of displacement. But I also think the suspicion on the Left about building in general is, at least sometimes, misplaced. For example, the Trinity Place development is building hundreds of new market-rate apartments, but, as the result of the hard work of the SF Tenants Union, previous tenants are getting new (and better) apartments in the new buildings at their old, rent-controlled rates. And of the projects you’ve highlighted with red arrows, things they’ve replaced include the former AAA office, a closed gas station, a car dealership, and a bunch of surface parking lots.

We need to strengthen rent-control laws, increase affordable housing requirements for new buildings, etc. When these policies are working as they should, new buildings can be good for everyone. But our focus should be on improving these policies, rather than trying to save parking lots and abandoned gas stations.

thanks for writing this –

Nice post Chris. Just shared it with folks on Twitter. The transformation of SF from a bohemian paradise to brogramville is depressing.

I’ve made a few trips to Europe recently, and our housing policies seem totally primitive / brutal / stupid compared, though even there the pressures to privatize seem to mount. I’m not expert, but I talked to some folks in the city gov of Vienna about it. It works something like this. Cities like Vienna that have 20%+ public housing (high quality and affordable) attract more people to the city, the city can’t keep up, so they feel pressure to turn to public / private partnerships and private developers to create new housing stock.

Thank you for this in depth post. It has helped me feel less isolated. As a renter I have felt very threatened this year by the changes in my neighborhood of Bernal Heights. I fear that our eviction notice my come soon if the owners pounce to sell on this current trend. Next door was sold and then flipped for $1.3M, a foreclosure across the street (that displaced a family of 4,) is now being redeveloped and will surely be sold for over a million as well. It has been unpleasant to deal with developers, feel the character of the neighborhood change, and feel (again) how low we are on the economic totem-pole (at least for, as you mention, SF). If we can’t hang on here, we would certainly be East Bay bound if we chose to stay in the area at all. Will certainly check out these books!